Brian Dominick is the author of Present as Prologue: A GenZero Novella, which describes the first phase of a youth-led, high-tech revolution in America. We talk about youth liberation, education, capitalism, and the liberatory possibilities and limitations of technological change. Interesting discussion about the idea of youth as a class.

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 38: The East is a Podcast

I talk to Sina Rahmani, host of The East is A Podcast, about everything from genre conventions to Orientalism and Edward Said to podcasting culture and trying to reach an audience as a podcaster.

Readings for leftist parents

A little video talking about some of the readings on parenting I found most helpful, and most compatible with leftist values (equality, freedom…)

The Brief Episode 3: Blockade standoff

Police move in on the Mohawks at Tyendinaga, setting off a further wave of blockades, disruptions and direct action from coast to coast. Anna Zalik joins us to discuss the oil and gas industry, and Gord Hill talks indigenous resistance.

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 37: Postcoloniality and the Racist Legacy of the British Empire

A wide-ranging and admittedly bookish discussion with William Patterson historian Navyug Gill and frequent guest and sometimes host of the show, Dan Freeman-Maloy. We talk about postcolonial studies, history, and the British Empire, and the ways that its racism lives on.

The Brief Episode 2: Blockades expand

After the RCMP raided and dismantled the Wet’suwet’en roadblocks, rail, port and transportation blockades have spread across Canada in solidarity.

And they are growing.

The Brief on Wet’suwet’en

Our new podcast. This episode: on the Wet’suwet’en evicting Coastal GasLink in Canada, and the RCMP raid on behalf of the pipeline company.

Includes an interview with Jeffrey Monaghan, co-author of Policing Indigenous Movements: Dissent and the Security State (Fernwood 2018), and a passage from Nick Estes’s book Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance.

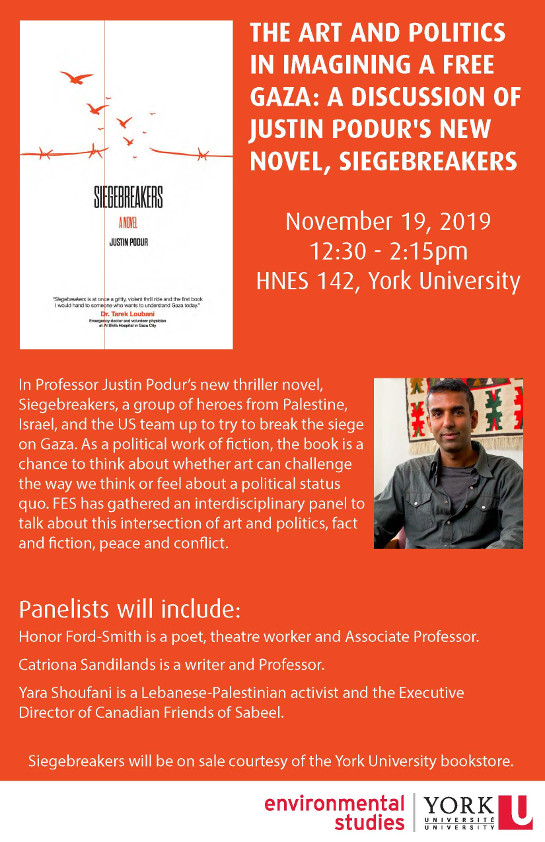

Anti-Empire Project Episode 36: Siegebreakers at York University

On November 19, 2019, York University’s Faculty of Environmental Studies hosted a panel called “The Art and Politics in Imagining a Free Gaza: A Discussion of Justin Podur’s new novel, Siegebreakers.” It featured poet, theatre worker, and Associate Professor Honor Ford-Smith; writer and Professor Catriona Sandilands; and Lebanese-Palestinian activist and Executive Director of Canadian Friends of Sabeel, Yara Shoufani. The event began with me reading Chapter 1 of Siegebreakers, and interventions by the panelists followed.

So, if you still haven’t read Siegebreakers, you can let me read the first chapter to you!

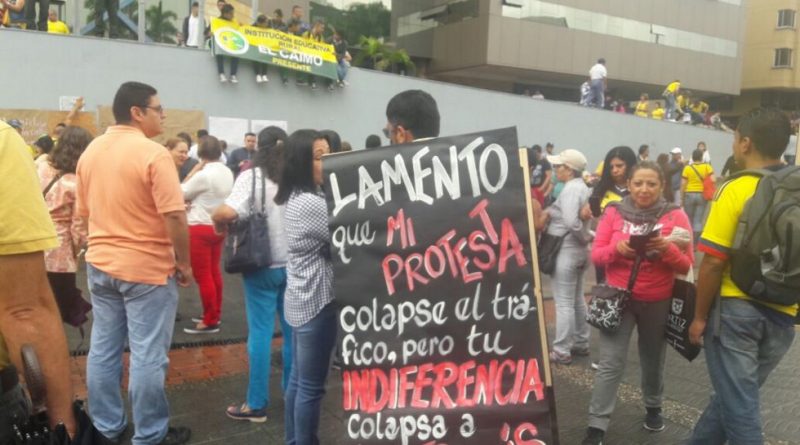

The people of Colombia are cracking up the walls of war and authoritarianism

The protests that started with the national strike called by Colombia’s central union on November 21 to protest pension reforms and the broken promises of the peace accords have persisted for two months and grown into a protest against the whole establishment. And the protests have continued into the new year and show no signs of stopping.

The end of the decade has seemed to bring an unstoppable march of the right wing in Latin America as elsewhere. The 2016 coup in Brazil that ended with fascist Jair Bolsonaro in power, the 2019 coup in Bolivia, the continuously rolling coup in Venezuela, all showcased the ruthlessness of the U.S. in disposing of left-wing governments in the region. Right-wing victories at the ballot box occurred in Chile in 2017 and in Colombia in 2018, where the electorate rejected the left-wing Gustavo Petro and embraced Iván Duque, a protege of the infamous former president Álvaro Uribe Vélez. But with the new wave of protests, the unstoppable right-wing juggernaut is facing many challenges.

In Chile, three months of protests, still going, are demanding the resignation of President Sebastián Piñera and the reversal of a range of neoliberal policies. Even in the face of the police and army using live fire against protesters, they have not let up.

Ecuador is another peculiar case, in which Lenín Moreno ran as a candidate who would continue left-wing policies, but who promptly reversed course upon reaching power in 2017, including revoking the asylum of Julian Assange, who is now in a UK prison. Reopening drilling in the Amazon, opening a new U.S. airbase in the Galapagos, getting rid of taxes on the wealthy, and doing a new package of International Monetary Fund austerity measures was enough to spark a sustained protest. Moreno’s government was forced to negotiate with the protesters and has withdrawn some of the austerity measures.

In Haiti, protests have gone on for over a year. Sparked in July 2018 by a sharp increase in fuel prices (the same spark as for the Ecuador protests), they have expanded to call for the president’s resignation. In Haiti, as the protests have dragged on, some of the country’s elite families have joined the call for the president’s resignation, which will make it even more difficult to find a constitutional exit from the crisis.

In Colombia, after winning the runoff in 2018, President Duque may have felt that he had a mandate to enact right-wing policies, which in Colombia have usually included new war measures in addition to the usual austerity. But combining pension cuts with betraying the peace process was simply stealing too much from the future: Young people joined the November 21 protests in huge numbers (the lowest estimates are 250,000).

The sustained nature of the protests is striking. Rather than one-offs, the protests have been committed to staying on until change is won. We may hear more this year from post-coup Brazil and Bolivia as well.

At the heart of Colombia’s protest is the issue of war and peace. To say Colombians are war-weary is an understatement. The war there that began (depending on how you date it) in 1948 or 1964 has provided the pretext for an unending assault on people’s rights and dignities by the state. Afro-Colombians were displaced from their lands under cover of the war. Indigenous people were dispossessed. Unions were smeared as guerrilla fronts and their leaders assassinated. Peasants and their lands were fumigated with chemical warfare. Narcotraffickers set themselves up inside the military and intelligence organizations, creating the continent’s most extensive paramilitary apparatus. Politicians signed pacts with these paramilitary death squads. The war gave the establishment an excuse for the most depraved acts, notably the “false positives” in which the military murdered completely innocent people and dressed their corpses up as guerrillas to inflate their kill statistics. Even though the guerrillas, with their kidnapping and too-frequent accidental killings of innocents, were never popular with the majority, Colombians have backed peace processes when given the chance. And Colombians didn’t look kindly at the major betrayals of peace processes in the past, like the one in the 1980s, when ex-guerrillas entering politics were assassinated by the thousand. From 2016, when the new peace accords were affirmed, until mid-2019, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) tallied 138 of their ex-guerrillas murdered; more than 700 other activists were killed in the same period, including more than 100 Indigenous people since Duque came to power in 2018.

At the end of August, a group of FARC members led by their former chief negotiator, Iván Márquez, announced that they were returning to the jungle and to the fight. They argued that the assassination of their members and the refusal of the government to comply with the other aspects of the accords demonstrated that there was no will for peace on the side of the government. Those FARCs who announced they were giving up on the accords were treated as having gone rogue: The government labeled them as criminal groups. Aerial bombardment (a war measure not normally the first recourse in dealing with “criminals”) quickly followed. When a bombing (also in August) by the Colombian air force of one of these rogue groups in Caquetá killed eight children and Duque labeled it “strategic, meticulous, impeccable, and rigorous,” he was greeted with much-deserved public revulsion. Duque was shaping up to deliver the same kind of war as always, only now under the flag of peace, its victims labeled criminals instead of guerrillas.

Eternal war does benefit some: those in the arms and security business especially, and those who want to commit crimes under the cover of war. But despite the many benefits of eternal war for the elite, normalcy also exerts a powerful draw. When Duque’s mentor Álvaro Uribe Vélez was elected president in 2002 and 2006, it was with the promise of normalcy—of peace—through decisive victory over the guerrillas. Instead, he delivered narco-paramilitarism, false positives, and, very nearly, regional wars with Ecuador and Venezuela.

One of Uribe’s early acts was to negotiate a peace agreement with the paramilitaries. Since the paramilitaries were state-backed, organized, and armed, this was a farcical negotiation of the government with itself. But when some of the paramilitary commanders began to speak publicly about their relationships with the state and multinational corporations, they found themselves deported to the U.S. At the time, the scandal was given a name—“para-política.” But to some of the investigators, it was better-termed “para-Uribismo.” Paramilitary commander Salvatore Mancuso—who had the temerity to talk about the Chiquita banana corporation and who is apparently going to return to Colombia sometime soon—is just the best-known name. Many others have found that being a paramilitary leads to a considerably shortened lifespan. Uribe, mayor of Medellín and governor of Antioquia during the heyday of the cartels, is named in numerous official documents as being close to both the narcotraffickers and the paramilitaries. The evidence keeps coming, as courts, now trying Uribe’s brother, keep getting closer to the man himself.

After the first round of “Uribismo,” it was time to try a peace process. The betrayal of that process, initiated in 2012, and the new president Duque’s promise of yet another decade of “Uribismo,” has been a motivating force of the recent protests.

Uribismo entangles endless war with austerity and inequality. In a recent Gallup poll, 52 percent of Colombians surveyed said the gap between rich and poor had increased in the past five years; 45 percent struggled to afford food in the previous 12 months; and 43 percent lacked money for shelter. The social forces that typically fight for social progress and equality—unions and left-wing political parties—have traditionally been demonized as proto-guerrillas. With the government declaring the war over—and with great fanfare—people want the freedom to make economic demands without being treated as civil war belligerents.

But when faced with the November 21 protests, the government went straight to the dirty war toolkit, murdering 18-year-old protester Dilan Cruz on November 25, imposing curfew, detaining more than 1,000 people, and creating “montajes,” the time-tested use of agents provocateurs to commit unpopular and illegal acts to provide a pretext for state repression. Government officials have also tried to claim that Venezuela and Russia (of course) were behind the protests.

Part of the dirty war toolkit is to negotiate, and the government has been doing so with the National Strike Committee. No doubt hoping that the protests will exhaust themselves and any agreements can be quietly dropped as numbers dwindle, the government is dangling the possibility of dropping some austerity demands. Meanwhile, the negotiators are being threatened by paramilitary groups, and another mass grave of those murdered as military “false positives” has been unearthed. Uribismo has wormed its way into every structure of the state: Real change will have to be deep. By not giving up easily, the protesters have shown the way. These protests could be a crack in the walls of fascism that seem to have sprung up everywhere in the past decade.

Justin Podur is a Toronto-based writer and a writing fellow at Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute. You can find him on his website at podur.org and on Twitter @justinpodur. He teaches at York University in the Faculty of Environmental Studies. He is the author of the novel Siegebreakers.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Dealing With Your Pro War Iranian Friends

Because the world didn’t end last week, I’ve recorded another video. After a quick roundup of what happened since the US assassination of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani, I spend some time talking about how to deal with pro-war diasporas who say things like: “I’m Iranian and I support this war, and so should you.”