Brian Dominick is the author of Present as Prologue: A GenZero Novella, which describes the first phase of a youth-led, high-tech revolution in America. We talk about youth liberation, education, capitalism, and the liberatory possibilities and limitations of technological change. Interesting discussion about the idea of youth as a class.

Category: Fiction

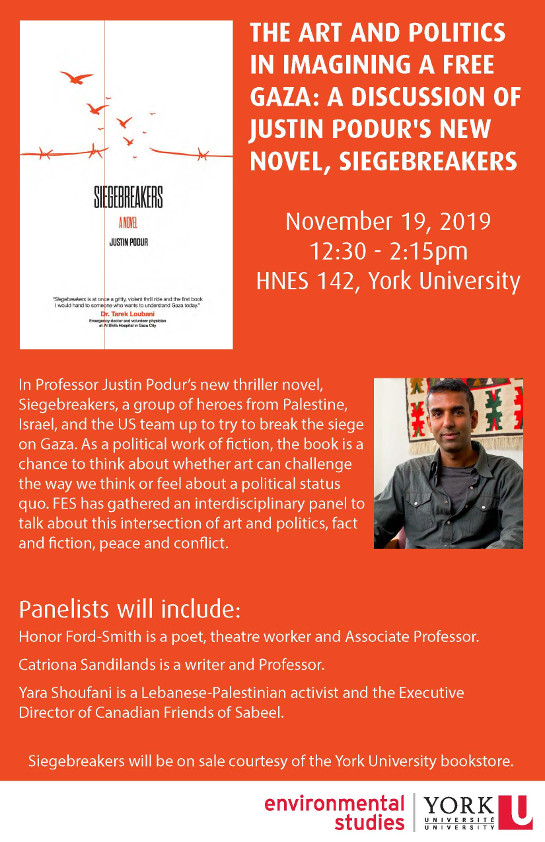

Anti-Empire Project Episode 36: Siegebreakers at York University

On November 19, 2019, York University’s Faculty of Environmental Studies hosted a panel called “The Art and Politics in Imagining a Free Gaza: A Discussion of Justin Podur’s new novel, Siegebreakers.” It featured poet, theatre worker, and Associate Professor Honor Ford-Smith; writer and Professor Catriona Sandilands; and Lebanese-Palestinian activist and Executive Director of Canadian Friends of Sabeel, Yara Shoufani. The event began with me reading Chapter 1 of Siegebreakers, and interventions by the panelists followed.

So, if you still haven’t read Siegebreakers, you can let me read the first chapter to you!

Siegebreakers launch in London Ontario – November 12, 2019

The poster looks familiar, sure, but why wouldn’t it?

Talking Siegebreakers with socialists

I had the privilege of being on the wonderful Oats for Breakfast podcast by the Socialist Project. The co-hosts, Umair Muhammad and Karmah Dudin, did an amazing reading of the book and I had a great time talking to them.

A discussion of Siegebreakers with journalist Jon Elmer

A discussion between Siegebreakers author Justin Podur and journalist Jon Elmer. Recorded on Oct 4/19 at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto.

Siegebreakers Chapter 5 – a reading

On October 4, 2019, I read Chapter 5 of my latest novel, Siegebreakers, at the book launch at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto.

Getting in and out of Gaza in Siegebreakers

In Siegebreakers, all of the main characters face a serious, and very concrete, problem: getting in and out of Gaza.

Some are trying to get out, and to do that, they have to go through Israel – through Erez Crossing, which is a scene out of a dystopian future. A few years ago I interviewed a doctor who had made the crossing. He talked a bit about what it was like coming and going from Israel, but I also put a description together (for the book) from that and a few other interviews of what it is like to go through Erez (I went through Erez myself in 2002, but that was before it was rebuilt into its current form):

Laila made the long walk through the wire-encaged sidewalk, like an enclosure at a zoo, to the first turnstile. Israel modified these turnstiles to reduce the space between the arms, to press harder against Palestinian bodies. Remote-controlled, of course, by the occupier’s security who watched her progress through the tunnel from above. Through the turnstile — if the invisible occupier chose to open it, by remote control — then, a big steel door. Also, remote-controlled. Once it opened, there was another long, outdoor passageway to the terminal. She rolled her bag along behind her, her shoulders slouching when she forgot herself, but when she remembered, with her back arched and her chin up. She faced the sliding steel doors at the entrance to the terminal, waited in suspense for the occupier’s decision to open or close it. They opened it for her, so she could go through the metal detector and the next set of turnstiles. She put her luggage on the carousel and it disappeared into another room, where someone working for the occupier went through her every possession. Then, the occupier used a scanner to create a three-dimensional model of every centimetre of her body… More remote-controlled doors. More modified metal turnstiles. Laila claimed her bag and went to face the occupier’s passport inspectors, who sat in blast-proof booths. She handed the inspector her documents...

I won’t spoil what happens next, but let’s continue on the problem of getting in and out of Gaza. Anyone trying to get goods in or out of Gaza has to use a different high-tech remote-controlled crossing, Kerem Abu Salem. The description of how that crossing works is assembled from the organization Gisha.org. Play a round of Safe Passage, if you’re up for the frustration.

And then there’s Rafah, the crossing to and from Egypt. Taking a look at Rafah is where you see how much a participant Egypt’s dictatorship is in the siege of Gaza.

Sea and air? Not happening. I wouldn’t even have my fictional characters try. Some years ago I was asked why people don’t just fly into Gaza through Yasser Arafat International Airport. Grand opening: November 1998. Grand closing (via Israeli bombs): October 2000.

The Great March of Return, which has shaped Gaza’s politics for over a year now and which is one event I didn’t anticipate in Siegebreakers, is about all of the rights that are denied to Palestinians, but it is deeply about the fundamental right to come and go, the right to not be born and live one’s whole life in a prison, which is Israel’s (and Egypt’s, and the US, and Canada, and all of the allies collaborating in the siege) design for every single person in Gaza (children included). Abby Martin’s new film, Gaza Fights for Freedom, filmed in large part by Palestinian journalists from Gaza, can show you what it looks like.

Those people marching to the fence every week? They’re the real-life Siegebreakers.

Siegebreakers launch in Toronto Oct 4, 2019 7pm

We are gonna launch Siegebreakers the evening of October 4th, at the marvelous Another Story Bookshop in Toronto, at 7pm. There’ll be a special guest there in addition to me, talking about the real Gaza. See you there!

‘The Butterfly Prison’ reignites hope for a better, more just world

The Butterfly Prison

by Tamara Pearson

(Open Books, 2015; $20.65)

Tamara Pearson is an independent left journalist from Australia who writes about Latin America. Her novel, The Butterfly Prison, set in Sydney, weaves together three different threads. In the following spoiler-filled review, I discuss each thread.

In the main thread, a young working-class woman named Mella leaves an unhappy home as a teenager, finding herself in an exploitative relationship while working in an exploitative retail job. At the job, she meets a friend, an Iranian refugee named Rafi, who introduces her first to union politics, then to radical politics, before being summarily deported to Iran and never seen again.

Mella has already become a part of an activist network by the time of Rafi’s deportation, so her growth continues without him. We read about Mella’s political awakening, her political education, and her participation in an ultimately successful revolution.

In the second thread, we read the story of an Aboriginal man named Paz as he grows up in a childhood marked by constant police harassment and violence. As a youth, he sets up a house with some young friends in the poor suburb of Macquarie fields, where they support one another and try to get by.

Paz takes shifts at a 7/11, works as an office cleaner for a few months; his friends busk in the subway, gamble for money, and make repairs in the neighbourhood. None of this is enough, as the police constantly return to raid their house, injure them, destroy their property, plant bugs, and make their lives intolerable.

In a (slightly) fictionalized version of the incident that precipitated the actual Macquarie fields riots of 2005, Paz is driving a car from a party when the police begin a chase. Paz loses control of the car, which crashes, killing one of his best friends. Paz surrenders to police and is imprisoned, where he lives the rest of his life, partly in solitary confinement, which destroys his sensitive mind. A fire in the prison sees him escape, but he has no options or hope, and commits a very violent suicide.

In the third thread, the author presents vignettes of incidents from various corners of the world. Inspired by Eduardo Galeano, the author turns a sensitive eye to environmental destruction, wasted human potential, and war, shown as the outcomes of the inequality and violence of capitalism.

The central metaphor of the book, which gives the book its title, is that each person has invisible butterfly wings, and that the system clips these wings and denies people their chance to fly.

Paz’s plot line, and the vignettes of the first few hundred pages, are unrelentingly bleak, violent, and overwhelmingly hopeless. Small acts of kindness, gestures of mutual aid and solidarity, pervade the lives of the characters around Paz, but they are ultimately all overwhelmed by the violence of the system.

Through Paz’s journey and his attempts to do everyday things like make rent, get paid at work, get from one part of town to another, or make a phone call in prison, we are shown in detail the evils of racism and the destructive absurdities of bureaucracy as they play out in Paz’s life and death, and those of his friends.

Mella’s plot line and the sketch of the post-revolutionary society presented in the last 30 pages breaks the hopelessness, presenting some of the possibilities as the “army of the poor,” the revolutionary force awakened at the end of the book, rises. A series of more hopeful vignettes of examples of resistance accompany this late turn in the plot.

Unlike Paz and his friends, who are overwhelmed by the system and can only try to cope, Mella and the group of activists around her are able to act, not solely react.

When Mella fell in with the activists, I had a moment of fear that this would be yet another disillusioning experience, that they would be rigidly and inhumanely ideological, or exploitative in a new way, or cult-like (like the similar group presented in Doris Lessing’s book The Good Terrorist) — but no, this group stays true to their principles. Mella finds education, love, and ultimately, the revolution.

In both plot lines, the author presents us a different way of looking at familiar spaces. We see department stores and shopping malls, poor people’s subdivisions, a refugee detention centre, a prison, an activist office, an activist house, and street protests of different sizes. Most of the book consists of complex images wrought in long, poetic sentences, invented compound words, and original metaphors.

Showing the underside of a first-world city, the novel implicitly critiques the invisible privilege inherent in most fiction today (David Wong’s list on Cracked.com, “5 Ways Hollywood Tricked You Into Hating Poor People,” comes to mind, as The Butterfly Prison falls into none of these traps).

The Butterfly Prison isn’t perfect. It seemed to me that the author tried to encompass every issue, every destructive aspect of capitalism, in the chapters and the inter-chapters. The characters’ dialogue sounded very similar to the author’s voice and weren’t differentiated from one another. More could be done with plot, dialogue, and voice, to match the excellent work done setting the scene and providing description.

A few notes on the character, Paz, are in order. I had hoped that Paz and Mella would cross paths, that they might actually meet and do something together.

And while Paz’s plot line could be read as a parable of the ongoing genocide against Indigenous people in Australia (and Canada, and the U.S., among other places), I thought it unfair that there should be no hope for Paz while there was hope for Mella.

Leslie Marmon’s 1977 book, Ceremony, presented an Indigenous person going back to tradition in order to heal. Books by Indigenous authors from Canada don’t shy away from the violence of the colonial situation, but find strength and possibility in Indigenous traditions and spirituality: Richard Wagamese’s 2012 book Indian Horse, Tomson Highway’s 1998 Kiss of the Fur Queen, Lee Maracle’s 2014 Celia’s Song, all offer examples.

None of these books were easy reads, but I found the horror of Paz’s death after everything he went through in The Butterfly Prison especially deflating and demoralizing.

If the theme of the book is wasted potential, then perhaps Paz’s character is an example of wasted potential. The last 30 pages or so, after Paz’s death, are dedicated to showing some elements of the future society, which has a 15-hour work week, a sprawling education system, participatory councils deciding on production and distribution, and the chance to love, dance, and be close to nature.

Given all this, it is clear the book isn’t devoted solely to brutal realism, but is able to speculate about a better world. Couldn’t some of that speculation have encompassed Paz’s story? Couldn’t Paz have made it here, couldn’t he or other aboriginal characters have contributed to the decolonization of this new world? And what happened to the deported Rafi? Was there no chance of reconnection after the revolution?

A reader reading for plot, or to watch the journey of these characters, will find these loose or cut threads disappointing.

A reader who is looking for descriptions, images, and views of the world from a too-rarely represented political and aesthetic perspective, however, will not be disappointed.

Even in its most painful moments, The Butterfly Prison is a book of hope by a sensitive observer, deeply invested in the world and its people, who wants us to soar, who feels the pain of our clipped wings, and who writes in a way to ensure that we feel it too.

Justin Podur is a writer based in Toronto.

Published on the rabble book lounge: http://rabble.ca/books/reviews/2015/12/butterfly-prison-reignites-hope-better-more-just-world

Reading from and a review of The Demands of the Dead, Oct 10, 12pm, Toronto Public Library

I will be reading from the Demands of the Dead on Friday Oct 10, 12pm, at the Toronto Public Library. If you’re in the city, come and check it out.

I also wanted to call attention to the review of the book by Megan Cotton-Kinch at the Two Row Times, which was also republished at Countercurrents.org.

Here’s the event listing:

The Demands of the Dead: A crime novel by Justin Podur

Fri Oct 10, 2014

12:00 p.m. – 1:15 p.m.

75 mins

Toronto Reference Library, Elizabeth Beeton Auditorium

Here’s Megan Cotton-Kinch’s review:

Book review: A detective story set in the middle of an Indigenous insurgency

Demands of the Dead, By Justin Podur

Reviewed by Megan Cotton-Kinch

While I’ve always enjoyed a good detective novel, I’ve always felt like this genre usually contains an underlying message of support for the police, and never really takes a critical look at the role of “law-and-order” in maintaining a society based on the oppression of poor people and the theft of Indigenous land. At best, this kind of stories will look at corruption in police and politics but offer no solutions. This is where Demands of the Dead transcends the genre, and moves beyond works like The Wire by actually looking at the larger political context and offering possible solutions. In the case of Podur’s novel these are represented by the Zapatista Indigenous insurgency, which has an important presence in the book.

In the opening of Demands of the Dead, an ex-cop receives an email, in Spanish that says, “The dead demand so much more than vengeance.” But the dead are more than the two dead police, or his dead friend, but include all the dead in southern Mexico who have been killed in the counter-insurgency. And unlike most books in the detective genre the novel does offer up the possibility of solutions that go beyond personal vengeance.

Did Zapatista guerrillas murder two police officers? Or was it the Mexican police? Or drug traffickers? What were the police, in the political context of an armed uprising, doing on Zapatista territory anyway? The main character “Mark” is in southern Mexico to investigate. But in reality he is there to investigate the murder of his best friend, a progressive lawyer and activist, back in New York, by cops on the force he used to serve on.

The novel, and its protagonist “Mark”, doesn’t shrink from looking at what it means to be an ex-cop, and ‘independent’ contractor working with semi-sponsorship from the American embassy and their proxies in the Mexican counter insurgency (police and military). Back in the States, Mark’s murdered best friend had told him, “You can’t help. You should just go. I don’t care what kind of person you are Mark. If you’re a cop, we’re enemies.” But Mark is not just an ex-cop, he also has wilderness survival and tracking skills, and a personal history that gives him connections to progressive lawyers and an inclination to cross into Zapatista territory to get their side of the story.

As asides into the two cases, one official and one personal, there are discussions of Zapatista political and military strategy, with people’s organizations and democratic decision-making as preferred weapons in a struggle, but with an armed self-defense strategy in reserve. Podur also shows what they are up against: a counter-insurgency strategy targeted at the Indigenous Zapatistia movement that is linked with machine politics, American imperialism and drug money.

Nonetheless, the novel has a very nuanced take on the state and police systems, seeing them worthy of analysis and full of contradictions.

The book has realistic fight scenes with descriptions to suit martial arts fans, and accurate descriptions of guns and military tactics. The main character’s wilderness skills are not overplayed but are realistic assessments of the kind of things that skilled trackers can do (hear people approach before they arrive due to concentric disturbances in the forest) and can’t do (find individual tracks of intruders on a heavily trafficked roadway). The one thing I’d wish for is more fully developed female characters with plot importance.

The author, Justin Podur, is better known as a non-fiction writer and commentator on political topics, including Indigenous issues and solidarity efforts with Palestine. He is a professor at York University who does research on forestry and forest fires. In the novel, this background is present but doesn’t overwhelm the story.

The novel is available for download or purchase as a book from Justin’s website http://podur.org/demandsofthedead