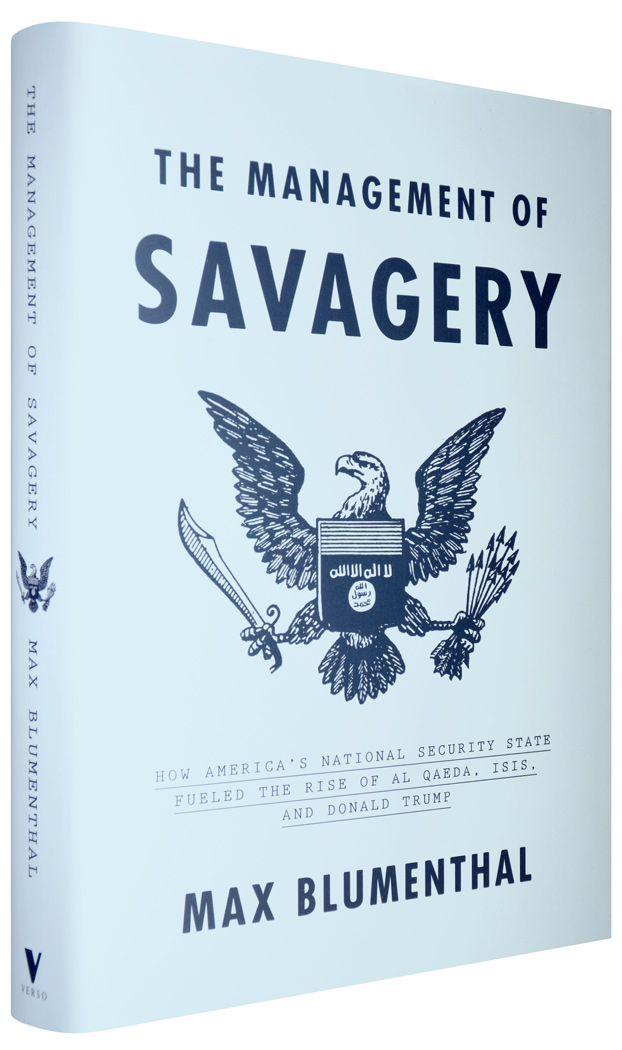

I talk to Max Blumenthal, author of The Management of Savagery: How America’s National Security State fueled the rise of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and Donald Trump. We begin with the latest coup attempt in Venezuela and go from there to talk about anti-imperialist politics, the need to rebuild an antiwar and anti-imperialist mentality, and the hunger for such a perspective – as evidenced by the positive reaction to Max’s book – despite it being pushed away from the mainstream.

Tag: ISIS

The Ossington Circle Episode 17: The Kingdom of the Unjust, with Laila

I talk to “Laila”, an activist who has studied the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for many years. For preparation, I read Medea Benjamin’s new book, Kingdom of the Unjust.

The Ossington Circle Episode 14: Clouds of War Gathering with Manuel Rozental

In this episode of The Ossington Circle, Colombian physician and activist Manuel Rozental returns from a trip to Turkey, during which he spent time with Syrian refugees, to talk about the advancing war in Syria and on the planet.

The Ossington Circle Podcast Episode 2 – Syria, Environment, War, and Refugees

This episode of the podcast is a lecture given on a panel at York’s Faculty of Environmental Studies on January 28, 2016. The panel was on Environment, War, and Refugees, and the lecture was on Western policy and the war in Syria.

The Reordering of Iraq and Syria

Written for teleSUR English, which will launch on July 24.

How far back do we look to understand the breakup of Iraq and the declaration by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in June 29, 2014 of a caliphate?

Do we start 11 years ago, in 2003, when the US invaded Iraq (in the operation called Operation Iraqi Freedom), occupied it, put Nouri al-Maliki’s government in power, and has supported it since?

Or do we need to start a decade earlier? The 2003 invasion was preceded by a 13-year regime of sanctions, starting in 1990/1, and periodic bombing that prevented Iraq’s economy from functioning, or developing. And the sanctions regime was preceded by a devastating bombing and invasion conducted by the US in 1990/1, Gulf War I (called by the US Operation Desert Storm). The death toll of Gulf War I and the sanctions is at least in the hundreds of thousands; The toll of Gulf War II and the occupation is estimated to be close to one million.

But let’s not forget that the 1990/1 Gulf War I, conducted by US President Bush I, came just two years after the 8-year long Iraq-Iran war, 1980-1988, which killed hundreds of thousands of people in each country (by conservative estimates) and devastated both.

Or, does it go even further back, to the post-WWI arrangements that imposed artificial, colonial boundaries on the countries of the region?

Not all of the blame for Iraq’s thirty years of war can be blamed on the US, or the West. Yes, the US supported Saddam Hussein in the war on Iran’s then-new regime in the 1980-88 Iraq-Iran War. Yes, the US conducted a multi-decade assault on Iraq starting in 1990. Yes, after the 2003 occupation, the US reorganized Iraq and its oil industry for its own ends. In spite of all that, much of what is happening in Iraq today are unintended consequences, rather than planned or anticipated consequences, of US actions.

But whether the explosion today in 2014 of the order the US imposed after 2003 was foreseeable by US planners then, or not, the US has been incrementally steering Iraq, Syria, and the rest of the region towards an order that, however horrific for the people living there, is tolerable for US power. That order consists of transnational refugee populations ministered to by international agencies, helpless civilians trapped in sectarian states or statelets, perpetual, low-level civil war on the ground, and US surveillance and assassination technology in the sky and on the sea.

When the US occupied Iraq in 2003, it deposed the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, who ruled over a country whose divisions he suppressed using the tools of a police state. Even though he favored one group (the Sunni) over the others (Shia and Kurdish), it was the US occupation that created the ‘security dilemma’ that forced everyone into sectarianism. By supporting Saddam’s opponents, the US effectively supported the Kurds in their movement towards autonomy and eventual independence, and the Shia, al-Maliki’s group, who are the demographic majority and who are close to Iran. A Sunni-Shia civil war broke out on US watch, and it was never resolved, except through a de facto partition – a separation of the populations who had before lived among one another.

A decade after the 2003 invasion, the government of Iraq, now nominally sovereign and no longer occupied, is in the strange position of being supported by the US and also by Iran. Their common enemies are Iraq’s Sunni insurgency, which has diverse threads, among which are those ousted by the 2003 invasion, as well as al-Qaeda and other religious and sectarian groups.

While supporting the increasingly sectarian (Shia) leadership of Iraq, and its Iranian ally, against the increasingly sectarian (Sunni) insurgency, the US also continues its decades-long absolute support for the Gulf monarchies, including Saudi Arabia and Qatar. These monarchies have their own sectarian agendas in the region, opposed to the Shia, in Iraq, in Lebanon, and against the ‘Alawi, a minority in Syria, to which the Syrian dictator, Bashar al-Assad, belongs.

This leads us to the name of the group that has declared the caliphate, ISIS – the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Even though the Arabic rendering does not include the name ‘Syria’, the English rendering of the group’s name is accurate enough. ISIS’s most spectacular military breakthroughs have come in Iraq, but they grew strong fighting alongside (and, alternatingly, against) al-Qaida and other insurgents against Assad’s regime in Syria’s now three-year old civil war, which has itself had hundreds of thousands of casualties. Assad’s external backers include Russia, Lebanon’s Hizbullah, and the US’s ally in Iraq, Iran. Syria’s insurgents are backed by US allies Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. So, the US is on both sides of this conflict.

This is not the only conflict that the US is on both sides of. The US invaded, occupied, and established a government in Afghanistan in 2001/2, overthrowing the Taliban, who retreated to Pakistan. The US spent the next decade fighting the Taliban from Afghanistan and also supporting Pakistan’s government, whose military establishment covertly supports the Taliban (as do the Gulf monarchies, also supported by the US).

What does it mean for the US to be on both sides of a conflict? Is the US working against itself? Does one hand not know what the other is doing?

Not exactly. For all their complex and contradictory dimensions, these conflicts have many important consistencies: the ones mentioned at the outset of this essay. They feature weak states, unable to protect their political sovereignty. Their economies are dysfunctional, unable to regulate or control multinational corporations that can operate freely according to rules they make up as they go along. Their populations are helpless, forced to work in the informal, illicit, and conflict economies, and for the educated, in the conflict-management and NGO economies. At the (literally) highest level, their military affairs are controlled by remote control US technology. The pattern is found in many countries: Afghanistan, Haiti, Palestine, the DR Congo – these are the models for the future of the region, and they are being steered methodically to that outcome.

The problem for Iraqis and Syrians is not artificial borders. All borders are artificial, and no re-partitioning of the countries will solve it. Nor are Iraq and Syria’s conflicts the outcome of a new, multipolar world order that is a result of collapsing US power. US power is not absolute and it may, indeed, be collapsing, but the strategy of the collapsing power might just be to ensure that everyone else collapses first. The shattered statelets of the middle east won’t fail to provide continued access for profit-making, humanitarian intervention, high-tech surveillance, and control.

Justin Podur blogs at podur.org and is based in Toronto.