Choosing our avatars carefully, we take you through the political ideologies of the 19th century. Conservatism (Burke, Metternich); Liberalism (Paine, Locke); Radicalism (Condorcet, Gregoire); Anarchism (Bakunin, Kropotkin); Communism (Marx & Engels); and we throw a few more in as well (nationalism, humanitarianism, romanticism). This episode will set you up nicely for the next round of revolutions – 1830, 1848, and 1870.

Category: Leftist theory

Occasional forays into leftist theory about what a good society might be like, and how leftists can use social theory to help understand the world.

Chomsky vs the Media, 2020 version

Chomsky signed a letter about free speech and something called “cancel culture“, which has prompted a small social media wave of responses.

There is a good piece by Jonathan Cook about how focusing on Chomsky’s signature misses the point. But I am going to focus only on Chomsky here.

My argument: Chomsky’s most powerful message is anti-imperialism. Containing that message has been the preoccupation of the propaganda system since the 1960s.

In 1973, they shut down a whole company and pulped the print run of his book with Ed Herman, Counter-Revolutionary Violence.

Mostly, though after the peak of protests, he was just driven out of the mainstream. He published with activist publishers and the alternative media.

Like Z Magazine and ZNet, one of the principals of whom was Michael Albert, who’s now… a podcaster.

Beyond marginalizing him, they also smeared him. Because he compared Indonesia’s Timor massacres to Cambodia massacres, they called him denialist.

A French publisher slapped a free speech essay he wrote on a holocaust denier’s book, and they smeared him about that.

In the 1990s, a new generation of people discovered Chomsky on the web. The web was different then. Not fully sealed up by the tech giants.

Chomsky’s influence grew and some of the alternative media also grew and became mainstream or close. By the time of the Afghanistan War 2001, he could no longer be marginalized.

Indeed it became a good careerist move to make a showy denunciation of Chomsky in the mainstream. It worked for Samantha Power, for example.

A hilarious 2005 interview by Emma Brockes in the Guardian resulted in a very extensive corrections page that was basically a retraction.

Johann Hari, who went somewhat downhill and then turned around and did some good work since, invented a comment by Chomsky at a luncheon.

George Monbiot did the same in the 2010s, and others.

These are just off the top of my head and intended to reveal the particular way that Chomsky was handled by the mainstream in the 2000s: try to introduce inaccuracies and falsehoods; prove your liberal credentials by denouncing Chomsky the leftist.

Chomsky’s influence didn’t stop, but the whole media ecosystem that he analyzed has changed. So has the strategy for containing him.

The strategy today is to select the views that he holds that are closest to the mainstream and amplify those, while de-emphasizing the anti-imperialism.

That’s what the Intercept does when it sends someone to interview Chomsky on how Biden is the lesser evil.

That’s what the new “cancel culture” petition is about.

Yes, Chomsky is a free speech absolutist, he’s a lesser-evilist on electoral politics, he’s a two-stater on Palestine, he broadly prefers nonviolent strategies, and is critical of every state, including those targeted by imperialism.

But can find those views everywhere in the mainstream. They are not why people admire Chomsky and they are not why imperialists hate Chomsky.

Chomsky says that every US president is a war criminal.

Chomsky talks about the US sanctions against Cuba.

Chomsky talks about the US-led counterinsurgency in Colombia.

Activists in every anti-war movement in the US since the Vietnam war have relied on Chomsky’s analysis and arguments; including movements against Israel’s wars in Lebanon & Occupied Palestine.

Chomsky talks about how propaganda systems work and push for war.

Chomsky believes in challenging the reader or audience: in Canada, he talks about Canada’s crimes, because it’s cowardly to denounce crimes you can’t affect while doing nothing about crimes you can affect.

There’s much more. My point: Chomsky is a proven person of principle, impossible to deny. The Biden people, the “cancel culture” people, they want to use that to advance their agendas.

As they do so, they want you to forget the anti-imperialism that is what Chomsky is really about and has been about for 50 years.

This is just the 2020 iteration of the campaign to contain Chomsky’s anti-imperialism.

Whether you’re disappointed that Chomsky signed that letter or newly concerned about cancel culture because Chomsky signed the letter, consider this option – read enough of his work to get a sense of what it is about, and if you like his ideas, principles, and methods try to assimilate them into your world view.

GUEST POST: 21st Century Fascism? I’m afraid so.

by Hector Mondragon, November 12 2018. Translated from Spanish by Justin Podur.

Facing the wave of growth and success of political and social movements of the ultra-right, it is necessary to ask: are we witnessing the rise of a series of fascist movements in many parts of the world as occurred in the 1930s? Or is fascism an unrepeatable historical phenomenon limited to the period between the two world wars?

Some consider that fascism only arose to prevent the victory of socialist revolutions or to stop the communists, but “fascism did not triumph when the bourgeois was threatened with proletarian revolution, but rather when the working class was weakened and put on the defensive.” The role of fascism was not to overcome the socialist revolution but to “erase the conquests of reformist socialism.”i

In Germany it was the social democrats that liquidated Rosa Luxemberg and Karl Liebnecht and stopped the communists fifteen years before the Nazi triumph. The Soviet Republic in Hungary was stopped by the invasion of the Rumanian army sent by the Liberal party. In Italy the occupations of the factories and the workers’ councils were stopped by the Liberal Party two years before the triumph of the fascists. Fascist propaganda insisted and insists always on a “communist threat” but for the past 90 years, capitalism has used the fascist “solution” to destroy reforms and human rights after the “communist threat” has been defeated.

What then is the difference between the Italian blackshirts, the German brownshirts, the Rumanian iron guards, the Ukrainian flagmen, the Hungarian arrow cross, the Spanish falange or the Croation Ustache – and today’s ultra-right parties?

All of the protagonists of European fascism of the last century professed a visceral hatred of Jews, expressed in extreme form in Germany, Ukraine, Romania and Croatia and culminating in the Holocaust. Today, by contrast, with the exception of Ukraine’s Svoboda, Hungary’s Jobbik, Greece’s Golden Dawn, the KKK and a few small neonazi groups, the majority of the global right is pro-Israel and supports the extermination of the Palestinians.

In general, on the xenophobic right, anti-Semitism has been replaced by Islamophobiaii, hatred of refugees, and particular racisms, like that expressed on the US right against Mexicansiii. In other aspects, however, despite its diversity, the 21st century ultra-right bears a growing resemblance to the European fascism of the 1930

. This is not coincidence. Fascism is a phenomenon specific to the crises of certain phases of the imperialist and capitalist order.iv v vi

Those who believe in the “end of history” – that colonialism is a thing of the past and capitalism is the final historical order – incorrectly discard the notion of a rebirth of fascism. The reality is very different. In this century so far, imperialist wars have destroyed Iraq, Libya, and Syria, all as a way of resolving the cyclical crises of capitalism. The recolonization of the Middle East is a fact. Colonialism was in retreat during the period that began with the fall of Nazism and ended with the US loss in Vietnam. It has returned with force in the past three decades.

To understand how fascism arises from the necessities of internal and external imperial wars, Hitler’s January 27 1932 speech to the industrialists at Dusseldorf is instructive. This speech convinced big business to support the Nazi solution.vii

Hitler explained that the defense of private property required a dictatorship like that of the Fuhrer. Because private property is the result of economic inequality and different classes of citizens, to defend private property it would be necessary to impose political inequality, hierarchy, and authoritarianism. Hitler explained that England did not just go to India sell its wares; it obliged India to buy them by invading the country. If the businessmen wanted the success of their enterprises, they had to support Nazism to conquer new markets and resources in the wider world and destroy the “Bolshevism” that was damaging the racial and national unity needed for victory.

In this speech, unusually light on Hitler’s characteristic constant attacks against the Jews, Hitler focused on “Bolshevism”: not just the need to stop it, but also to stop it from dividing the people and spreading a mentality opposed to the singular national interest. The businessmen applauded loudly for several minutes. Hitler’s program for big German business included a wave of privatizationsviii ix – and was only stopped by the fall of Nazism itself.

For Milton Friedman and the Chicago School to impose neoliberalism on Chile, it was not just necessary to prepare an elite of Chilean economists. It was also necessary to install Pinochet’s “Patria y Libertad” to impose the laws of the market.

Vilfredo Pareto, the economist considered by neoliberals as the precursor of their “libertarian” ideas, raged against strikes as the enemies of an economic optimum. He hated the worker’s movement’s taking over factories. He celebrated the ascent of Mussolini to power. Even though Pareto himself was not a fascist, the fascists made him a senator-for-life. In the first few years of his government, Mussolini followed Pareto’s prescriptions to the letter, destroying political liberalism, reducing state administration in favor of private enterprise, reducing property taxes, favoring industry, and imposing religious education.x The capitalists and neoliberal economists would prefer not to associate with fascists and repudiate their ideology, but they acclaim it when it is time to smash “Bolshevism” and go to war with other countries.

As it did 90 years ago, fascism today liquidates the gains of workers and collective rights, cleanses universities and schools, and promotes war. When the domination of transnational capital is not maintained merely by the laws of the market, it is maintained by direct violence. When institutional solutions are insufficient, the mass mobilization of one part of civil society is used against the rest.

Colonialism has strengthened. What is today called “extractivism” was once called “accumulation by dispossession”. It reigns throughout multiple parts of the world, an expression of the strength of colonial enterprises that have existed for centuries. It is the exact same primitive accumulation that occurred in the original phase of colonialism.xi xii

In the 20th century, war was integrated with colonial enterprise and the destruction of competitor capital (as we saw in Iraq, Libya, and earlier in Yugoslavia) in a way that foreshadowed the destruction of local capital, the conquest of new markets, new investment zones and sources of land, minerals, gas and petroleum.

But imperialism, colonialism and war are not in themselves fascism, which is a mass movement based in the middle class and the unemployed, mobilized in diverse forms – including armed militias – to destroy workers’ rights and organizations and perpetuate war in the interests of transnational capital and landowners. In Latin America, the landowners always have their paramilitary bands at the readyxiii.

In contrast to other forms of authoritarianism, the success of fascism is guaranteed by the mass mobilization of the middle class against the “enemies of the nation”, be they Jews, Communists, Africans, refugees, Muslims, or Mexicans.

As the Nazi philosopher Martin Heidegger said, “ …it can accordingly seem that there is no enemy. It is then a fundamental requirement that the enemy be found, brought to light, or even created so that this stand against the enemy may take place… with the goal of complete extermination.”xiv

The state that persecutes the enemy, according to the theorists of nazism, is not merely the judicial institution, but the people’s Being intrinsically united with its leader (Heidegger). It’s not a state machinery, but the people organized by the nazi party organized through its Fuhrer that is the source of law (Rosemberg). It is not the law that establishes order, but the “movement” that imposes an order, from which the law springs(Schmitt).xv

This is why Gramsci, in his Prison Notebooks, presented the thesis that civil society is itself a form of the state. This makes the problem of emancipation more complicated and more dramatic. “Civil society could very well express violence and oppression not inferior to that of the state, and very unscrupulous besides, and it will tend to exercise this violence without obstructions since it has no concern with even the pretense of impartiality.”xvi

The idea of needing to attack an enemy was and is a part of an ultra-right wing strategy, with false information used to agitate about the fantasy of the enemy. The great theorist of what is now called “fake news” was the publicist of Siemens and the Reemtsma tobacco company, Hans Domizlaff, who began his application of marketing techniques to politics in 1932.xvii

According to Domizlaff, “people can believe in gross lies or, in any case, there can be found freedom for action if lies are openly told and obstinately maintained…xviii the masses cannot be educated, only domesticated, led, and voided.”xix

In the 21st century the role of enemy is assigned in Europe and the US to migrants, especially refugees or to “terrorist” Muslims. In Latin America it continues to be “communists”, the political left, as it was in the time of the Doctrine of National Security.

But more and more, in the north and in Latin America, LGBTQ communities are targeted, called the “gender ideology”, with propaganda about apparent “scientific” research into gender. This is not new.

Homophobia was one of the hooks the Nazis used to win over religious sectors. Magnus Hirschfield’s theory of the “third sex” and his books on homosexuality and transgender were attacked. Hirschfield’s Institute for Sexual Research was the target of homphobic attack. Its administrator Kurt Hiller was sent to a concentration camp in March 1933 and on May 6 the building was occupied and its archives, photos, and library were confiscated to be burned in the famous book-burning of May 10, 1933.xx

The bonfire linked the “judeo-bolshevik conspiracy” and the third sex. Homophobia played a mobilizing role in the bonfire and in the concentration camps. The annihilation of the third sex occurred alongside the extermination of communists, unionists, Jews and Roma – the extermination of the enemy. The state apparatus, from its perch in the universities to its gas chambers, was rooted in the “people’s Being” directed by its leader.

The ultra-right of the 21st century, especially in Latin America, has rediscovered the role of homophobia. The struggle against “gender ideology” was embedded in the “No” vote against the Colombian peace accords and has moved millions of votes from Brazil to the US, including Costa Rica, where an important group of churches joined these homophobic manipulations with enthusiasm.

The manipulation of religion by the ultra-right is not limited to homophobia. For more than one hundred years the right has developed a theology of war. The spread of Wahhabism in the Muslim world has served as the basis for Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, and the “dispensationalism” of Cyrus Scofield has played a role in the West in creating a war theology, nourishing militarism on the evangelical right-wing.

The Islamic State is apocalyptic: it is preparing for the final battle of history, in which Jesus and the Mahdi will fight alongside them. “Dispensationalism” also views war in the Middle East as anticipation of Armageddon and considers US support for Israel part of a divine plan. The faithful expect to be transported directly to heaven before seven years of great disasters, at the end of which will occur the great battle of Armageddon, when Jesus will return to defend Israel.xxi

As the Nazis struggled against the conspiracy outlined in the “protocols of the elders of Zion”, the Latin American ultra-right struggles against the conspiracy of the Forum of Sao Paolo, which they believe wishes to impose communism and homosexualism. Bolshevism, however, has changed: it is no longer a Jewish conspiracy but the source of conspiracy, since Israel is now an ally and the Palestinians the enemy.

The ultra-right of the Americas is diverse, but its common symbols and leaders are always anti-communist, loyal to the US, and loyal to the transnational corporations. Under these three principles, religious fundamentalism can easily co-exist with the debauched life of Donald Trump. The white supremacists of the US are not in agreement among themselves about anti-Semitism. But the Klan and the neo-Nazis continue to co-exist and to coordinate on common projects like the wall on the border with Mexico.

The ultra-right in Europe is more divided. There are anti-EU and pro-EU ultra-rightists. There is one anti-Semitic right and another Islamophobic right. In Israel, the extermination of Palestinians signals fascism; in Islamic countries it’s Wahhabism; in India it is Hindu supermacy and there is even a Buddhist right-wing in Thailand and Burma. All of the ultra-rights deny our common humanity, are xenophobic and racist, homophobic and enemies of human rights and of international law.

Not every ultra-right is fascist. Several have given rise to diverse Bonapartes,xxii xxiii whether by electoral movements or by military-parliamentary-or judicial coups. Laws and repressive means strengthen state oppression, but fascism is not simply the repression of the system towards its enemies. The triumph of fascism is a qualitative change. xxiv xxv

For fascist regimes to establish themselves it is not sufficient for there to be a fascist party, nor is it sufficient that the president be a fascist. Fascism requires a mass movement that is capable of smashing the organizations of workers and of minorities, and capable of supporting perpetual wars. Fascism in the 21st century is reaching that point.

It is time to resist.

i BAUER, Otto (1936) Zwischen zwei Weltkriegen?. Bratislava: Eugen Prager Verlag, p. 136.

ii HUNTINGTON, Samuel 1997 O Choque das Civilizações e a recomposição da ordem mundial. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Objetiva.

iii HUNTINGTON, Samuel 2004. ¿Quiénes somos?: los desafíos a la identidad nacional estadounidense. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

iv MANDEL, Ernest (1969) El Fascismo. Revolta Global, p.10.

v POULANTZAS, Nicos (1970) Fascismo e Ditadura. Porto: Portucalense, 1972, p. 13.

vi DIMITROV, Jorge (1935) “La ofensiva del fascismo y las tareas de la Internacional Comunista en la lucha por la unidad dela clase obrera contra el fascismo”; Informe ante en VII Congreso Mundial de la Internacional Comunista, 2 de agosto de 1935. Selección de trabajos. Buenos Aires: Estudio, 1972.

vii HITLER, Adolf (1932) “The Dusseldorf Speech of 1932”; C N Trueman editor. The History Learning Site, 22 May 2015.

viii BUCHHEIM, Christoph and Jonas SCHERNER (2006).”The Role of Private Property in the Nazi Economy: The Case of Industry”. The Journal of Economic History 66(2) 390-416 (406). Cambridge University Press.

ix BEL, Germà (13 de noviembre de 2004). “Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany”. Universitat de Barcelona i ppre-IREA.

x BORKENAU, Franz (1936) Pareto. New York: John Wiley & Sons, p.40.

xi HARVEY, David (2004) “El ‘nuevo imperialismo’: acumulación por desposesión”; Leo Pantich & Colin Leys (Ed.) El nuevo desafío imperial, p.p. 99-129. Merlin Press-Clacso.

xii MARX, Karl (1867) El Capital, v. I, c. XXIV-XXV. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 1974, p.p. 607-650.

xiii See the character Attila in the film Novecento, by Bernardo BERTOLUCCI (1976).

xiv HEIDEGGER, Martin. Gesamtausgabe, 36/37, Sein und Wahrheit. 1. Die Grundfrage der Philosophie. 2. Vom Wesen der Wahrheit, Frankfurt am Main, Klostermann, 2001, éd. por Hartmut Tietjen, [GA 36/37], 90-91.

xv FAYE, Emmanuel (2005) “El derecho y la raza: Erik Wolf entre Heidegger, Schmitt y Rosenberg”. Heidegger: La introducción del nazismo en filosofía. Madrid: Akal, 2009, 2018, capítulo7.

xvi LOSURDO, Doménico 1997. “Com Gramsci, para além de Marx e Gramsci”; Crítica Marxista 3-4. Roma.

xvii DOMIZLAFF, Hans (1932) Propagandamittel der Staatsidee. Altona-Othmarschen.

xviii DOMIZLAFF, Hans (1952) Brevier für Könige. Massenpsychologisches Praktikum. Hamburg, Institut für Markentechnik, p. 208.

xix Ibidem, p. 288.

xx BAUER, Heike (2017). The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture. Temple University Press, p. 92.

xxi SIZER, Stephen (2006) Sionismo cristiano ¿hoja de ruta a Armagedón? Bósforo libros, 2009.

xxii THALHEIMER, August (1928) “Über den Faschismus”; internes Dokument der Komintern, 1928 ; Gegen den Strom, theoretischer Zeitschrift der KPD(O), 1930.

xxiii TROTSKY, Leon (1934) “Bonapartism and Fascism”; New International, 1(2): 37-38.

xxiv Ibid.

xxv DIMITROV, Jorge; op. cit.

translated by Justin Podur

Civilizations Series Episode 12a: South American Independence pt1 – Miranda and Bolivar

The struggles for Independence against the Spanish Empire rocked the Western Hemisphere at the beginning of the 19th century and changed the world. We focus on Simon Bolivar to tell this story in two parts. In this part, the Precursor, Francisco de Miranda, and the first half of Simon Bolivar’s campaigns.

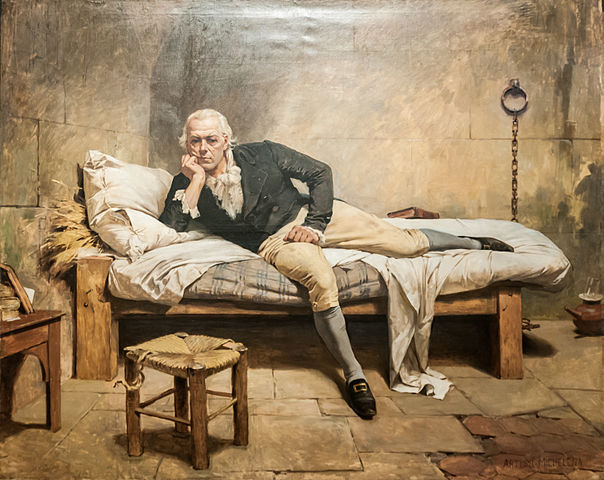

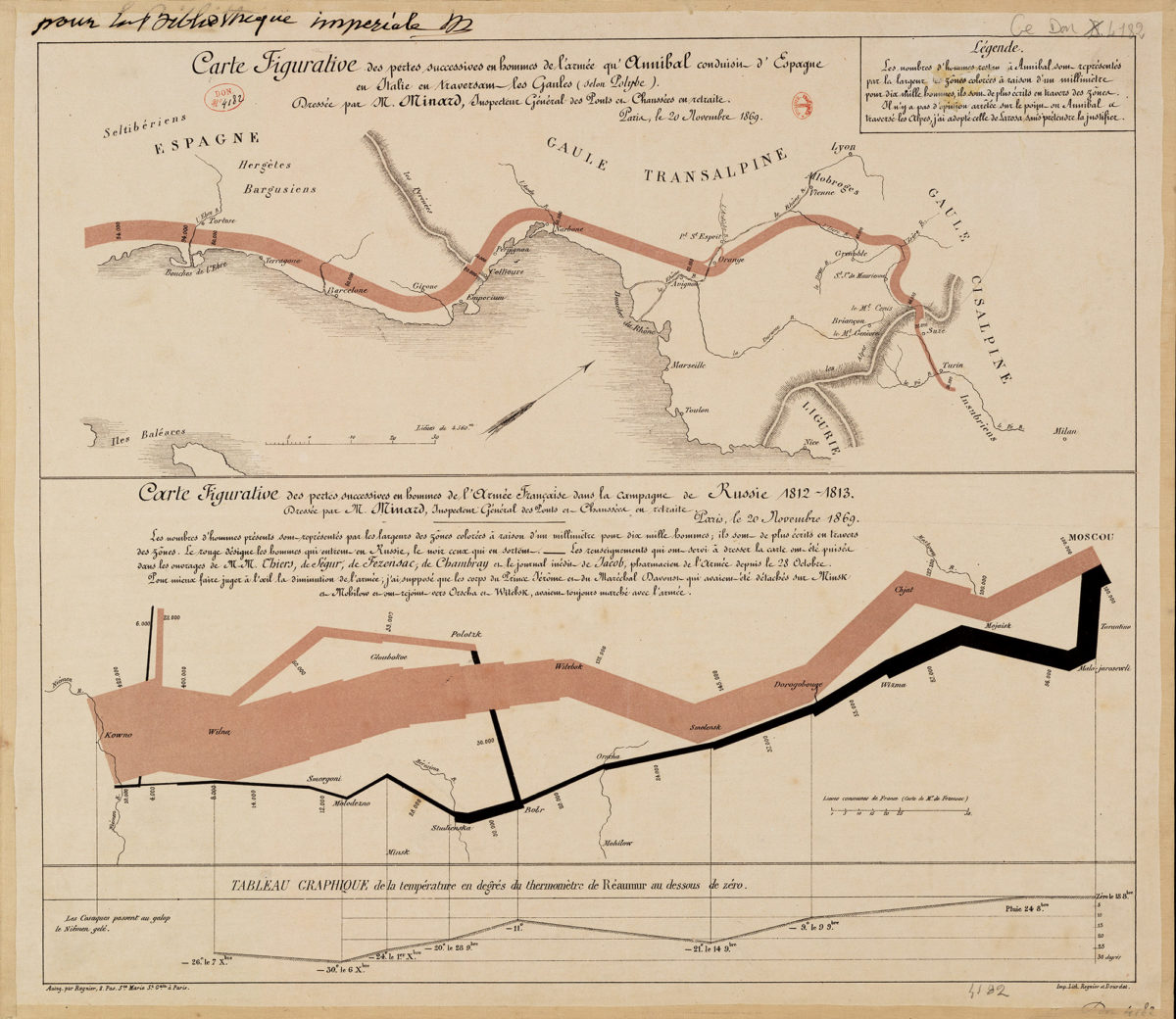

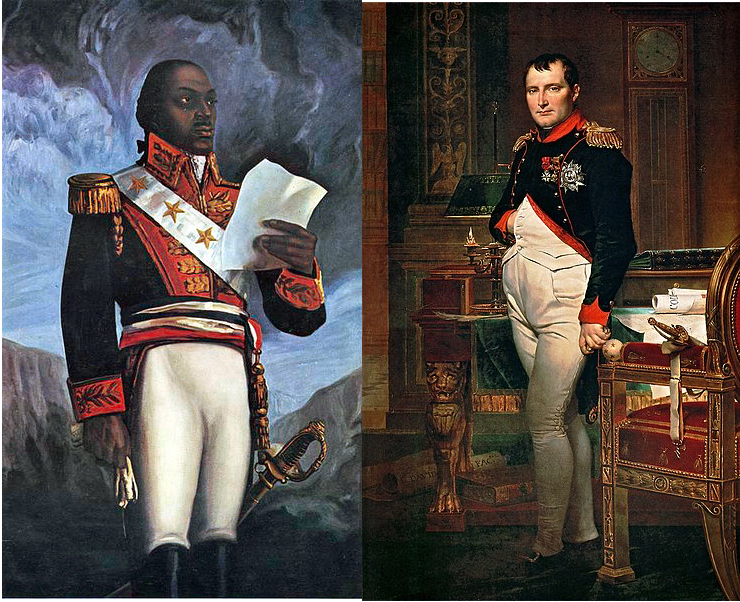

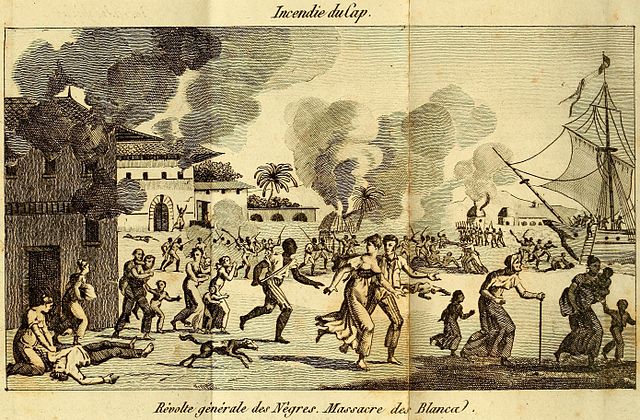

Civilizations 11e: The Haitian and French Revolutions pt5: aftermath

Dessalines became Emperor of Haiti in 1804, marking the end of the Haitian Revolution. Napoleon’s crowning as Emperor was the end of the French one. We talk about Napoleon’s wars, compare Napoleon’s exile and imprisonment to Toussaint’s, and talk about the momentous consequences of these revolutions.

Policing Is Irrelevant for Public Safety—Here Are Some Alternatives That Are Proven to Work

Society doesn’t need a large group with a license to kill.

Recent protests, catalyzed by the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, call for an end to racist police violence. With their actions, the protesters have also moved beyond many of the stale policing debates of the recent past. Defund, disband, abolish—people who would never have even heard these words in discussions about the police are now seriously considering them.

The breakthroughs in the police debate would not have been possible without the protesters, who have remained steadfast despite being beaten and abused by police everywhere in the United States. But this is not about making a breakthrough in the debate. This is about life and death. To stop police from killing people, 1,000 a year, year after year, changes will have to be made to the system. The protesters will be vindicated only if the changes made are the right ones.

Reform programs will only be successful if they start from the premise that the policing institution has lost its social legitimacy, which it never deserved. Reforms that assume police legitimacy—whether they involve more body cameras, better oversight, a more diverse force, or more prosecution of killers among the police—do not do the job.

Once the police are viewed as an illegitimate institution, we are well on our way. As Mariame Kaba argues in the New York Times, we could do worse than to make a 50 percent cut to police budgets and let the logic of austerity get the job done, as it has with the rest of the public sector. But 50 percent can be bargained down to 10 percent, and 10 percent to 2 percent, as long as police and their advocates can continue to link public safety with policing. The backlash against abolishing police as “politically unrealistic” in light of public safety has begun at the local level where the issue is being debated.

The goal has to be to abolish the class of people who have the legal right to end lives (and to lie to you while you must tell the truth).

Do police currently have the right to kill? Absolutely. Using conservative estimates and public data, writer Lee Camp calculated that police killed an average of 900 people per year—in other words, at least 12,600 people from 2005 to 2019. In this period, Camp writes, a total of three police officers were convicted of murder and had those convictions stand up to appeal. That is less than one-tenth of one percent, but it rounds off cleanly to zero.

The license to kill, above all, must be taken away from police. It survives because of a mystique—helped by ubiquitous cop shows, books, and movies—which is based on three notions: the idea that they are courageous because their job is dangerous, the idea that they keep society safe, and the fact that you can call them in an emergency.

Courage? Yes, policing is the 16th most dangerous job in America, behind logging workers, fishing workers, pilots, roofers, refuse collectors, truck drivers, farmers, steelworkers, construction workers, landscapers, power-line workers, grounds maintenance workers, agricultural workers, construction trade helpers, and the first-line supervisors of mechanics, installers, and repairers. But no worker in any of the top 15 most dangerous jobs has the option of killing when they subjectively feel unsafe—police do.

Safety? Police have no special function keeping society safe. In Alex Vitale’s book The End of Policing, he cites criminologist David Bayley’s earlier book Police for the Future, in which Bayley calls this one of the “best kept secrets of modern life. Experts know it, the police know it, but the public does not know it.” We have known for 50 years that police don’t help public safety. French anthropologist Didier Fassin, in his 2013 book Enforcing Order, cites the Kansas City experiment of the 1970s:

“This unprecedented study, unique at the time, compared three zones of the city: in the first, ‘reactive,’ crews limited their activity to responding to residents’ calls; in the second, ‘proactive,’ they at least doubled the time they spent on patrol; in the third, serving as a ‘control’ zone, they continued their previous mixture of activity. The results of a full year of operations and measurement appeared identical: neither attacks on persons, whether assault and battery, sexual assaults or muggings, nor attacks on property, whether burglary or damage to vehicles, varied significantly as a result of the different systems implemented; similarly, the experience of crime and the feeling of insecurity as reported by residents and business owners showed no variation between the zones, nor did the level of satisfaction with the police; and it turned out that in all three cases, 60 percent of the officers’ time was spent on activities not directly related to law enforcement, including a quarter bearing no relation at all to police work… Ultimately, it was evident that the patrols used preventatively had no effect on crime, either in terms of offenses recorded by law enforcement or from the point of view of residents’ perception of risk.”

The results were ignored: police kept patrolling for the next five decades. Fassin, who hung out with Paris police as part of his study, made his own calculations of how they spent their time:

“In my experience, time spent in response to calls often amounted to approximately 10 percent of the shift time; it was rare that it rose to 20 percent (five calls per team per night shift was a maximum that was rarely reached), with the rest of the time being devoted to random patrols, and to the administrative recording of actions taken.”

Think Paris is anomalous? Think again:

“A number of studies conducted in the United States reveal that officers on patrol spend between 30 and 40 percent of their time responding to calls (on average five calls per team per hour in cities), only 7–10 percent of which are related in some way to offenses or crimes, and between 40 and 50 percent of their working day on random patrol and paperwork, with the rest of the time devoted to various tasks.”

Here’s how Fassin describes the daily work of the police he observed:

“Cruising around quiet streets and peaceful neighborhoods, the police wait for occasional calls that almost always turn out to be pointless, either because they relate to mistakes or hoaxes, or because the teams arrive too late or bungle the case due to their clumsiness, or because there is no cause for any official questioning or arrest.”

Fassin cites a criminologist from Ontario, Richard Ericson, who in 1982 found that police spent 76 minutes out of an eight-hour shift responding to calls, arguing that “the presence of police officers has become an end in itself.”

So, police have the 16th most dangerous job, and they are irrelevant for public safety—but society needs someone to call in an emergency. This role can be filled by trained civilian workers who will have to learn to solve daily social problems without a license to kill, which could be the direction Minneapolis goes given city councilors’ vow to disband the police in their city. Last year Canada’s Globe and Mail reported about a police force in Yukon that carried no weapons and could lay no charges. Some cities have child protection workers that operate to protect children with greater or lesser degrees of intrusiveness. Social workers can be trained to intervene in domestic disputes and in active mental health crises in the field. They can be deployed in teams that ensure one another’s safety, like in other professions. There are detailed proposals for taking responsibility for safety into the hands of the community—Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò describes one in Dissent Magazine; Zach Norris reframes the issue in his new book We Keep Us Safe; and Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha describe community approaches to safety in their edited volume Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement.

There should be some cultural reforms too. Boots Riley suggests removing police and military consultants, who act like state censors, from movie and TV production. The #MeToo movement led to the creation of an intimacy coordinator role in film production, to ensure that sex scenes could be filmed without sexist exploitation. Studios could be responsive to this movement by drastically reducing their cop show production while removing censors for the shows that remained. This would go some way to reduce police mystique and police worship.

Police advocates may argue there might be some financial losses from abolition. Some police forces “eat what they kill” through civil asset forfeitures, fines, and tickets, keeping taxes low while making poor people’s lives miserable. Overall, however, money will be saved.

Initially, much of the money saved by defunding police would have to go to easing the transition of the people currently in police roles into other jobs. Pensions are a mechanism for taking police off the line for whatever reason, which police organizations use generously indeed. But pensioning every police officer indefinitely, while it would save lives, would not make any resources available for public safety. Instead, governments can provide retirement and retraining packages (the courageous police might look at retraining for one of the 15 more dangerous jobs) for them, as they do with other workers who are laid off.

For the duration of current union contracts, police could be paid to prepare for other jobs or simply to stay home—expensive in the short term, but it would save thousands of lives. After that initial period, the hundreds of billions of dollars that are spent on policing could be redirected to create and expand public services. The possibilities would be limited only by the number of billions that could be moved from police. Social workers, certainly, are a strong candidate to redirect funds toward, as well as free transit and other free basic services (especially health care in the United States).

Criminological data has told us for decades that police are irrelevant for public safety. Other data tells us a lot about what does influence safety. British researchers Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in their classic 2009 book The Spirit Level show that a large number of social problems, including violence, correlate strongly with inequality. Their work also shows different options for achieving equality: high wages by private employers (as in Japan) or high taxes and redistribution (as in Northern Europe). In the United States, every option for increased equality has been blocked by the wealthy who have—as Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page make clear in their important 2014 study—captured politics. A real Green New Deal would do more for public safety than any conceivable police reform short of abolition.

Author Bio: Justin Podur is a Toronto-based writer and a writing fellow at Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute. You can find him on his website at podur.org and on Twitter @justinpodur. He teaches at York University in the Faculty of Environmental Studies. He is the author of the novel Siegebreakers.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Civilizations Series Episode 11d: Haiti wins Independence, Napoleon becomes Emperor. French and Haitian Revolutions pt4.

It took Dessalines to complete the job of winning Haitian Independence, after Napoleon had Toussaint captured and imprisoned to die in France. Napoleon went on to make himself Emperor of France and start what seemed like an interminable series of wars. This takes us to the end of both revolutions.

Civilizations Series Episode 11c: Haitian and French Revolutions pt3

This phase of the French and Haitian Revolutions was dominated by two very dominating figures: Toussaint L’Ouverture and Napoleon Bonaparte. We talk about their rise and how they surpassed their rivals and would end up facing one another.

Civilizations Series Episode 11b: Haitian and French Revolutions pt2

The Haitian Revolution started with a well-planned conspiracy led by a slave named Boukman in 1791. The French Revolutionaries scrambled to figure out how to preserve the crown jewel of their colonies while accommodating their newfound principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. In France, the revolution went from monarchy to Republic to the best-known symbol (sadly) of the revolution, the guillotine. Part 2 of our series on the Haitian and French Revolutions takes us from 1791-1794.

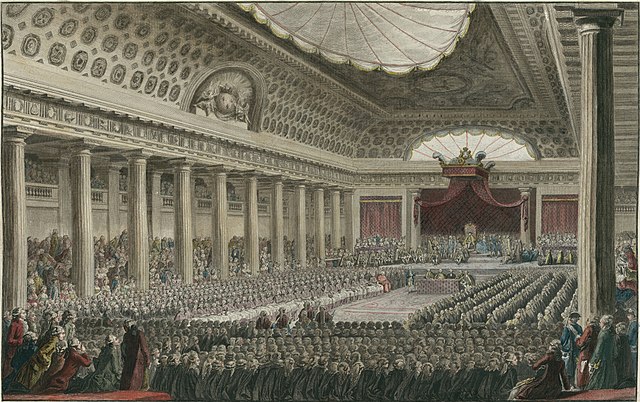

Civilizations Series Episode 11a: French and Haitian Revolutions pt1

Chinese diplomat Zhou Enlai may or may not have said 200 years later that it’s too early to tell what the consequences of the French Revolution are, but we are dedicating five full episodes to it and doing it right, which means treating the French and Haitian revolutions together. In part 1 we go from the Storming of the Bastille to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen and on, getting as far as 1792.