The New Zealand Parliament Protest inspired by Canada’s Trucker Convoy and with similarly hard-to-read politics; the continuing urgency of Maori sovereignty; An in-depth discussion of Donna Awatere’s extraordinary 1984 text, Maori Sovereignty; the connection between Chile and New Zealand; and a history of the Maori struggle since colonialism. With Simon Barber, Gabriella Brayne, and Arama Rata.

Author: Justin Podur

In Real Time with Stan Cox 11: Atlanta’s Cop City and Anti-Climate Legislation

Stan and I talk about two of his articles from April: the first on Atlanta’s “Cop City”, which one activist has already been killed by police over, and why it’s an environmental disaster as well as other kinds; and another article on Republicans trying to locally legislate to prevent any climate action from happening at the local level. Once again the US is blessed, instead of one big fascism the US has many small fascisms at the state level. In Real Time 11.

The Mexican Revolution pt3: The Downfall

Obregon defeats Zapata and Villa in battle. Carranza betrays the workers’ unions. The Morelos commune lives on, though its leaders fall one by one until Zapata himself. Villa too. And Obregon. And Carranza. We ask, what was it all for? And we give you the answers of some historians of the revolution: it was not in vain!

Mexican Revolution pt2: Villa and Zapata take Mexico City

Porfirio is out, Madero is in, but he has the same problem: how to stop the invincible peasant revolution now in motion? And the answer is, he can’t! Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata take the capital, but the seeds of their downfall and of their glorious peasant revolution are already laid. Part 2 of our miniseries on the Mexican Revolution.

The Mexican Revolution pt1: The end of the Porfiriato

The Mexican Revolution was an extraordinary event in 20th century history. In part 1 of our miniseries on the revolution we give the background from the Mexican-American war to the end of the quarter decade of Porfirio Diaz. The class balance of forces leading to the revolution and the dramatic events. We also talk about the main book Justin is using, Adolfo Gilly’s La Revolucion Interrumpida, written by an Argentinian-Mexican revolutionary in a Mexican prison! The intro and outro music for this episode is the Mexican Revolutionary song, La Cucaracha, performed by the Castilians. Listen to it at archive.org: https://archive.org/details/78_la-cucaracha-the-mexican-cockroach-song_the-castilians-stanley-adams_gbia0004379

World War Civ 14b: Anglo-German Naval Race pt2 – The Dreadnoughts

We talk about the fearsome dreadnought, the race to build it, the Le Queax novels that were the Red Dawn of the 19th century, the Heartland theory of history, and conclude our discussion of the naval race. The tensions are getting high…

AER 124: China’s use of telepathy and WeChat to control Canadian elections, with Carl Zha

Carl Zha is back and I try to explain to him the hysteria of the accusations by the CSIS leaker in Canada of Chinese electoral interference. He can’t find a word of it in Chinese media which leads to the horrible possibility that Canada doesn’t matter very much to China. I try to explain to him what has been going on in the Canadian media and he reminds us that Australia has been concocting the same story – anonymous intelligence sources using the media to create a scandal around supposed Chinese electoral interference – since 2017. It’s hard to take seriously, so we don’t.

World War Civ 14a: Anglo-German Naval Race pt1 – Theorists and Practitioners of World Domination

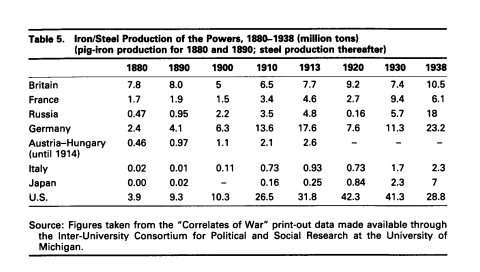

Part 1 of 2 on the Anglo-German Naval Race. We start with a modern theorist, Paul Kennedy, and his thesis that industrial power translates to military power. Then some earlier imperialist theorists we’ve mentioned before: Mahan and Mackinder, who Justin finally read. Then, the practitioners of naval power, Admiral Tirpitz on the German side and Fisher on the English. The first of two parts on the Anglo-German Naval Race leading up to WW1.

Subimperialism and multipolarity: Brazil’s dilemma

A look at sub-imperialism and multipolarity in Brazil historically and into the future.

In the Open Veins of Latin America Eduardo Galeano described an 1870 genocidal war of regime change waged on Paraguay by a Triple Alliance of its neighbors, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, on behalf of British imperialism. The target, nationalist president Solano Lopez, died in battle. The country lost 56,000 square miles of territory. Paraguay’s population was reduced by 83.3 percent.

By the end, Galeano wrote: “Brazil had performed the role the British had assigned it.” Before the intervention, “Paraguay had telegraphs, a railroad, and numerous factories manufacturing construction materials, textiles, linens, ponchos, paper and ink, crockery, and gunpowder… the Ibycui foundry made guns, mortars, and ammunition of all calibers… the steel industry… belonged to the state. The country had a merchant fleet… the state virtually monopolized foreign trade; it supplied yerba mate and tobacco to the southern part of the continent and exported valuable woods to Europe… With a strong and stable currency, Paraguay was wealthy enough to carry out great public works without recourse to foreign capital… Irrigation works, dams and canals, and new bridges and roads substantially helped to raise agricultural production. The native tradition of two crops a year, abandoned by the conquistadors, was revived.”

After the war: “it was not only the population and great chunks of territory that disappeared, but customs tariffs, foundries, rivers closed to free trade, and economic independence… Everything was looted and everything was sold: lands and forests, mines, yerba mate farms, school buildings.”

Summarizing all this, Galeano wrote: “Paraguay has the double burden of imperialism and subimperialism.”

“Subimperialism,” Galeano continued, “has a thousand faces.” Paraguayan soldiers joined an intervention against the Dominican Republic in 1965, under the command of a Brazilian general, Panasco Alvim. Paraguay “gave Brazil an oil concession on its territory, but the fuel distribution and petrochemical business [was] in U.S. hands.” The U.S. also controlled the university, the army, and the black market as well, of which Galeano wrote: “Through open contraband channels, Brazilian industrial products invade the Paraguayan market, but the Sao Paulo factories that produce them have belonged to U.S. corporations since the denationalizing avalanche of recent years.”

Elaborating on Brazil’s sub-imperial function since 1964, Galeano wrote: “A very influential military clique pictures the country as the great administrator of U.S. interests in the region, and calls on Brazil to become the same sort of boss over the south as the [U.S.] is over Brazil itself.”

Ruy Mauro Marini Analyzes the Phenomenon

It is perhaps no coincidence that the leading scholarly authority on sub-imperialism is the Brazilian scholar Ruy Mauro Marini. Mauro’s 1977 article was published shortly after Galeano’s book. To understand “global capitalist accumulation and subimperialism” some background on the theory of imperialism set out by Lenin is in order, and more recent books like Zak Cope’s The Wealth of Some Nations and Patnaik and Patnaik’s A Theory of Imperialism teach the theory eloquently.

The key concepts are unequal exchange and value transfer, magical processes through which the wealthy countries exchange smaller amounts of labor for larger amounts of labor from the poor countries. The mechanisms are many: patent regimes, Western corporate control of Global South resources, denomination of oil and other commodities in U.S. dollars, IMF and Western-bank loan terms and draconian rescue packages, Western arms sales and military training programs—all backed up by the threat of sanctions, coups, invasions, and “color revolutions,” which happen frequently enough to remind Global South governments to stay in line.

In Imperialism, Lenin described the pressure on wealthy countries to “go imperialist:” winners in the Western domestic market invariably consolidate and tend towards monopoly; these winners are invariably coordinated increasingly through banks and financial interests; throwing new investments in to a mature market brings lower returns than they can get in newly opened ones, so the financiers seek colonies to get high returns on their growing piles of capital; the colonies also address their interests in labor and raw materials that are cheap (or ideally, free, through theft).

Mauro shows how this dynamic can lead to sub-imperialism if the context is right. Sub-imperialism, he writes, is “the form assumed by the dependent economy when it reaches the stage of monopoly and finance capital,” and it has two basic components.

The first is a “relatively autonomous” expansionist policy that functions under the overall umbrella of U.S. hegemony.

The second is what Mauro calls a “medium” organic composition of capital. To explain this concept an example comparison will suffice: an economy with a high organic composition of capital is one where workers use advanced, costly machinery that itself required a lot of labor to produce (the word “composition” refers to how much so-called “dead labor” went into the machines on which the “living labor” is now laboring). These are the workers in the vacuum labs making nanometre-precise computing chips. An economy with a low organic composition of capital is one where workers labor with their hands or simple tools, cutting sugar cane with machetes as day laborers. Their work is called “unskilled” and their wages are proportionately lower.

In 1977, Mauro argued that in Latin America, only Brazil had both the medium organic composition and the relatively autonomous expansionist policy. But what about today? And what about in other regions?

Generalizing the Concept

Are there sub-imperialists in South Asia? Pakistan exercises its ambitions in Afghanistan under U.S. hegemony. Imran Khan was overthrown in a coup for withdrawing support for the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan; his successors have worked hard to prove their subordination to the hegemon. India meddles in the affairs of its small neighbors like Bhutanand does so under U.S. hegemony; Western corporations certainly have an immense footprint in both India and Pakistan.

In the Middle East, Saudi Arabia and Turkey qualify as sub-imperialists though both showcase how each sub-imperialist is a special case. In Africa, South Africa has been analyzed as a sub-imperialist and tiny Rwanda could well qualify as a Central African version.

Who doesn’t fit? None of the U.S. Five Eyes partners (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or UK) nor Japan, nor Israel, since all are high-income countries with higher than “medium” organic composition of capital.

Nor do China, Russia, or Iran fit the sub-imperialist mold. They may exercise hegemony—or contest it—in their regions, but they do not do so under the umbrella of U.S. hegemony.

This brings us back to Brazil and to the changes in the world since the writings of Mauro and Galeano on sub-imperialism.

Sub-Imperialism and Multipolarity

Until very recently, unilateral U.S. hegemony was the basic fact of world affairs.

No one could contest the U.S. invasions of Grenada, Panama, Iraq, or Haiti or its destruction of Yugoslavia and Libya. But Russia and Iran did contest the U.S. plan to dismantle Syria in 2015.

When Yemen voted against the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 1990, they were told that it was “the most expensive vote they ever cast” and punished economically. But by 2022 many countries remained neutral in the Russia-Ukraine War despite Western demands that they support Ukraine. India and China ignored Western demands that they refuse to buy Russian energy, expanding a series of options for trading commodities in currencies other than the U.S. dollar. African countries need not beg Western commercial banks for development finance: they can examine Western offers side-by-side with the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative. In 2023, China brokered a peace deal that restored relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

These developments reveal a historical change from a unipolar to a multipolar world order. The world has been under unipolar Anglo-American hegemony since the 1750s. There were world empires prior to that (notably the Spanish and Portuguese) but China and India each had around 25 percent of the world economy even at that time; a few centuries earlier, before the devastation of the Americas, the world was even more multipolar, if much less globalized.

If we are indeed moving away from the unipolar historical pattern, current sub-imperialists have some re-thinking to do: the U.S. umbrella is not what it once was.

Sub-Imperialism or Multipolarity? Which Way for Brazil?

With Lula (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva) back in the president’s office in Brazil as of 2023, the country faced this precise dilemma. In his previous tenure, Lula acted as both a multipolarist and a sub-imperialist. An early proponent of multipolarity (before the moment had even arrived) through his advocacy of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and of Latin American integration, Lula’s Brazil played the sub-imperial role as well, leading the morally compromised and disastrous UN mission to take over the U.S. occupation of Haiti. Some of the military officers who led the Haiti occupation helped overthrow Lula’s party in the coup that led to his jailing and eventually to Bolsonaro’s destructive presidency.

Bolsonaro was certainly, symbolically sub-imperialist: he saluted the U.S. flag and marched under the Israeli one. But most of his time in office was characterized by a disastrous COVID-19 response, genocidal policies against Indigenous peoples, and a general incoherence on foreign policy. Bolsonaro participated in a regime change stunt in Venezuela but tried to stay out of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Lula returned to office in a context of weaker domestic left-wing movements but a stronger multipolar context. Lula’s Brazil voted with the West in the condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but Brazil was told by Russian diplomats that Russia understood the vote.

There are economic considerations beyond the organic composition of capital that can drive Global South leaders back into the criminal arms of the U.S.—dependence on natural resource exports and foodgrain imports are tendencies that are difficult to reverse, especially in democracies like Brazil that are vulnerable to coups or regression when the right-wing returns to power.

Perhaps Brazil will be the vanguard of multipolarity in the Americas, or the sub-imperialist agent undermining BRICS from the inside. The changing world includes possibilities never contemplated by Galeano, Mauro, or Lenin.

Justin Podur is a Toronto-based writer and a writing fellow at Globetrotter. You can find him on his website at podur.org and on Twitter @justinpodur. He teaches at York University in the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

In Real Time 10: A 5-year and a 50-year farm bill

Back with Stan Cox on the environmental file. Stan’s written a dispatch on the Farm Bill. How the 5-year Farm Bills used to have consensus but how even that might be breaking, and then we talk about Wes Jackson’s ideas about a 50-year farm bill, thinking on the scale we probably need to be thinking on…