A 20-minute video about the assassination of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in Iraq by the US, the context, and the need for an antiwar movement.

Author: Justin Podur

The Ossington Circle Episode 35: The Turkish Invasion of Northern Syria with Sardar Saadi

I talk to friend and Kurdish Edition podcaster Sardar Saadi about the Turkish invasion of Syrian Kurdistan in October 2019, the brutality of Erdogan’s assault on the Kurds, the impossible dilemmas faced by the Kurds in the complex Syrian and regional war(s), and the role of the Empire in all of it.

Check out Sardar’s podcast, the Kurdish Edition

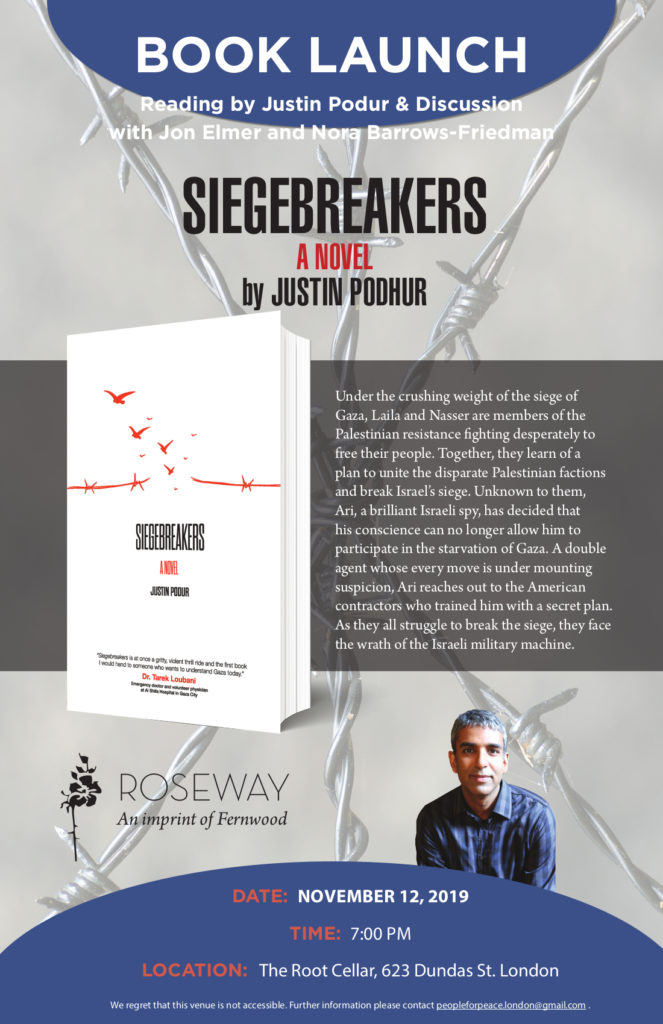

Siegebreakers launch in London Ontario – November 12, 2019

The poster looks familiar, sure, but why wouldn’t it?

Talking Siegebreakers with socialists

I had the privilege of being on the wonderful Oats for Breakfast podcast by the Socialist Project. The co-hosts, Umair Muhammad and Karmah Dudin, did an amazing reading of the book and I had a great time talking to them.

A discussion of Siegebreakers with journalist Jon Elmer

A discussion between Siegebreakers author Justin Podur and journalist Jon Elmer. Recorded on Oct 4/19 at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto.

Siegebreakers Chapter 5 – a reading

On October 4, 2019, I read Chapter 5 of my latest novel, Siegebreakers, at the book launch at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto.

Getting in and out of Gaza in Siegebreakers

In Siegebreakers, all of the main characters face a serious, and very concrete, problem: getting in and out of Gaza.

Some are trying to get out, and to do that, they have to go through Israel – through Erez Crossing, which is a scene out of a dystopian future. A few years ago I interviewed a doctor who had made the crossing. He talked a bit about what it was like coming and going from Israel, but I also put a description together (for the book) from that and a few other interviews of what it is like to go through Erez (I went through Erez myself in 2002, but that was before it was rebuilt into its current form):

Laila made the long walk through the wire-encaged sidewalk, like an enclosure at a zoo, to the first turnstile. Israel modified these turnstiles to reduce the space between the arms, to press harder against Palestinian bodies. Remote-controlled, of course, by the occupier’s security who watched her progress through the tunnel from above. Through the turnstile — if the invisible occupier chose to open it, by remote control — then, a big steel door. Also, remote-controlled. Once it opened, there was another long, outdoor passageway to the terminal. She rolled her bag along behind her, her shoulders slouching when she forgot herself, but when she remembered, with her back arched and her chin up. She faced the sliding steel doors at the entrance to the terminal, waited in suspense for the occupier’s decision to open or close it. They opened it for her, so she could go through the metal detector and the next set of turnstiles. She put her luggage on the carousel and it disappeared into another room, where someone working for the occupier went through her every possession. Then, the occupier used a scanner to create a three-dimensional model of every centimetre of her body… More remote-controlled doors. More modified metal turnstiles. Laila claimed her bag and went to face the occupier’s passport inspectors, who sat in blast-proof booths. She handed the inspector her documents...

I won’t spoil what happens next, but let’s continue on the problem of getting in and out of Gaza. Anyone trying to get goods in or out of Gaza has to use a different high-tech remote-controlled crossing, Kerem Abu Salem. The description of how that crossing works is assembled from the organization Gisha.org. Play a round of Safe Passage, if you’re up for the frustration.

And then there’s Rafah, the crossing to and from Egypt. Taking a look at Rafah is where you see how much a participant Egypt’s dictatorship is in the siege of Gaza.

Sea and air? Not happening. I wouldn’t even have my fictional characters try. Some years ago I was asked why people don’t just fly into Gaza through Yasser Arafat International Airport. Grand opening: November 1998. Grand closing (via Israeli bombs): October 2000.

The Great March of Return, which has shaped Gaza’s politics for over a year now and which is one event I didn’t anticipate in Siegebreakers, is about all of the rights that are denied to Palestinians, but it is deeply about the fundamental right to come and go, the right to not be born and live one’s whole life in a prison, which is Israel’s (and Egypt’s, and the US, and Canada, and all of the allies collaborating in the siege) design for every single person in Gaza (children included). Abby Martin’s new film, Gaza Fights for Freedom, filmed in large part by Palestinian journalists from Gaza, can show you what it looks like.

Those people marching to the fence every week? They’re the real-life Siegebreakers.

The idea of military stalemate in Siegebreakers

The oppressed in my novel Siegebreakers spend their entire page counts trying to resolve the military problem that seems to hold in several of today’s seemingly endless conflicts – whether it’s Israel’s wars on Gaza, in which the book is set, or it’s the Saudi dictatorship’s war on Yemen. In both cases, the more powerful side (Israel and Saudi Arabia), with all the backing and blessing that the US can provide, cannot seem to militarily defeat their outnumbered, outgunned opponents (the Palestinian resistance in Gaza – referred to simply as “Hamas” in the West, and the so-called “Houthis” in Yemen). So, the stronger side reverts to aerial bombing, destruction of civilian infrastructure, killing large numbers of civilians from the air, siege, blockade, and deliberate, genocidal destruction of the economy.

Israel’s 2006 war in Lebanon had a similar character: As it had decades before, Israel bombed the cities and invaded on the ground. Israel’s ground forces were defeated by their Lebanese opponents, Hizbollah. So they withdrew their ground forces and bombed the country for several weeks. In Israeli media there is frequent talk about the next war with Hizbollah, which is supposedly ‘inevitable’ (as is the next war with Gaza, as is war with Iran, etc.) In this hypothetical next war, Israeli leaders have pledged much more thorough bombing of Lebanon, including the usual promises to send it back into the stone age (the idea that these are war crimes seems no longer relevant: it may become relevant again). For their part, Hizbollah has warned that the next war won’t take place in Lebanon alone.

Returning to Gaza, the battle scenes in Siegebreakers are based on Israel’s 2014 war in the territory, and are portrayed, as the saying goes, from both sides. Ari’s experience as a soldier in the Israeli Army is drawn from various sources, but I highly recommend the report This is How We Fought in Gaza, by the group Breaking the Silence. If you find what Ari sees in Gaza shocking, read that report and you’ll see that, as I wrote in the Afterword, the most outrageous things in Siegebreakers are the true things. On the other side, Nasser’s experience fighting the invaders in Gaza draws from, among many other sources, Max Blumenthal’s book, the 51 Day War. Blumenthal traveled to Gaza shortly after the assault, while memories were still fresh, and documented what the war looked like on the Palestinian side. I got the chance to praise him for the book in a podcast in May 2019.

In Siegebreakers, the impasse gets broken in a particular way. I can’t tell you how, despite my love of everything to do with spoilers.

In a slightly better world, one with a powerful anti-war and anti-imperialist bloc within the US, these military impasses would lead to more energetic diplomatic initiatives. But in our world, there’s no need for diplomacy if you have America on your side (which apparently is cheaper and cheaper to attain). The fictional Siegebreakers rely on a few American dissident super-sleuths. The real-life Siegebreakers are part of a multi-decade slog to build an peace movement strong enough to change the current equation.

The Ossington Circle Episode 34: Colombia’s Peace Process Fails, with Manuel Rozental

I talk to friend and frequent guest Manuel Rozental about the breakdown of the (probably inaccurately named) peace process in Colombia, as FARC dissidents announce that the accords have failed and they are returning to war. We talk about war and peace in Colombian history and a global economy that profits more from war than from peace.

The project of de-exoticization in my novel, Siegebreakers

[This is one of a series of blog posts about the politics of my 2019 thriller novel, Siegebreakers, in which a team of heroes battles to break the siege on Gaza. Much of the politics and technology of the book is discussed and referenced in the Afterword: here I’ll take on specific issues once in a while and extend the discussion.]

One of the goals I had in writing Siegebreakers was to “de-exoticize” Palestinians, and along the way, Arabs and Muslims. The best way to explain what I mean is through an example.

In Siegebreakers, you won’t hear any of the Arab-speaking characters say “Allah”, “Inshallah”, “Ya Allah”/”Allahu Akbar”, or “Mashallah”. Instead, I use the most colloquial English translations: “God”, “If God wills it”, “Oh God”, or “Thank God”. In Western writing, media, and pop culture, using Allah instead of translating to God, or even using literal translations like “God is Great” instead of just “Oh God”, is exoticizing. It creates a distance between the Arab-speaking character and the English-speaking reader, and one that is unnecessary.

I say it’s an unnecessary distance because there are times when real cultural differences exist and come into play in interactions between people – on a human level and on a political one. But in the case of “Allah” and “God”, these words are used the exact same way by Arab-speakers and English-speakers, at the exact same times and in the same contexts. There isn’t a cultural difference between someone who sees something horrific and says “Ya Allah” in reaction and someone who says “Oh God”. It’s an artificial difference.

One way that Arabs great each other in the morning is to say “Sabah al Khair”, to which the response is “Sabah al Nur”. I’ve read one book (I won’t say which or by whom, no need to get into that here) where the author (a Westerner) renders the Palestinian characters saying “Morning of Joy,” and the response as “Morning of Light”.

What’s wrong with “Good Morning”?

That’s what I’d call exoticization – it really does just mean “Good Morning”.

Like so much in Siegebreakers (and I’d argue every other piece of art you’ve ever read, I’m just more honest about it) there’s a political agenda behind the de-exoticization. The distance between Western readers and even fictional Palestinians is part of what makes Westerners accept the injustices that are happening in Israel/Palestine. Exoticization extends that distance.

I don’t de-exoticize everywhere. Elsewhere in the book, reminding readers of the science-fiction nature of high-tech warfare and surveillance conducted on Palestinians by Israel is done through science-fiction like world-building techniques. The best exoticizer of the present that I know is author William Gibson. Decades ago, Gibson wrote science fiction (with a lot of implicit critique of corporate power and capitalism and where things were headed with computers and the internet…), whereas his more recent novels are set in the present, though they are still adventure books with extensive world-building, science, and technology in them. It’s just that our reality is science fiction now, so Gibson doesn’t have to speculate so much as describe the present.

When I went to Occupied Palestine in 2002, I felt my lack of Arabic and decided to remedy it (not entirely successfully, as you’ll see). Back in Toronto I took three years of university Arabic – it was my good luck to have the same Palestinian linguist for a professor even though it was at two different universities over several years. I got an A in Beginning Arabic, a B in Intermediate, and a C+ in Advanced (probably the plus was pity – I had too much going on by the time I was in advanced Arabic to apply myself properly). When I thought about how to render some of the Arabic conversations that I imagined, I heard my professor’s voice: she insisted that Allah was just the Arabic word for “God”, and that we translate it as such. So it’s not just a political or literary imperative: de-exoticization also keeps me out of trouble with my Arabic prof.