Instalment 2 of our monthly discussion on environmental topics with Stan Cox – this week Justin talks about some problems with what he calls “western environmentalism”; then we go over Stan’s latest dispatch (which will be up May 16 at citylights.com/blog) about voter suppression and protest suppression and how it’s changing US politics.

Author: Justin Podur

Scramble for Africa 18: Germany in the Scramble pt1 – from Karl Peters to the war on Mkwawa and the Wahehe

We begin the story of Germany in the Scramble for Africa with the question: was Germany really as bad as their enemies say they were? (spoiler: worse) We talk about Bismarck’s reluctance to own colonies, about why he started to change his mind as Germany caught a growing colonial fever; we talk about the harrowing career of Karl Peters, and then talk about the Germans in East Africa – the war on Mkwawa and the Hehe; the Maji Maji rebellion; and some short notes on Rwanda and Burundi under German control. The Herero and Nama genocides in Namibia will follow in the next episodes.

Anti Empire Radio 110: Karachi University Bombing – Balochistan and China

In the latest episode of Kung Fu Yoga with Carl Zha, we talk about the bombing at Karachi University where a suicide bomber killed herself, three Chinese teachers, and a driver. The Baloch Liberation Army claims responsibility. We ask: what does bombing Chinese teachers in Karachi have to do with Baloch liberation? What is going on in Balochistan? What is China’s footprint there and what are its investments? How is this event being perceived and understood in China? And what role does the US have in it?

Scramble 17: Brazza, Fashoda, and Cesaire’s Discours – France in the Scramble concluded

We start with a quick history of France’s theft of Congo-Brazzaville, centering on Brazza himself and ending with the Toque-Gaud Trial. Then on to the nearly early start of WWI – the Fashoda Crisis between Britain and France. Finally, we give the floor to Aime Cesaire to give us some commentary on what French colonialism in Africa meant and how to understand the specifics of France’s colonial crimes.

AER 109: Imran Khan’s ouster in Pakistan – coup or reconfiguration of power?

The ouster of Imran Khan continues to play out. We’re asking: 1. Was it a coup? 2. How can we understand Imran Khan’s foreshortened time in government and his ruling coalition? 3. How important are these events for the people of Pakistan – are they just elite maneuvering or do they have deeper implications? 4. How US-centric is too US-centric in understanding these things, as opposed to understanding regional actors and their roles and especially local power blocs and class dynamics. A friendly debate with Pakistani activist and academic Ayyaz Mallick.

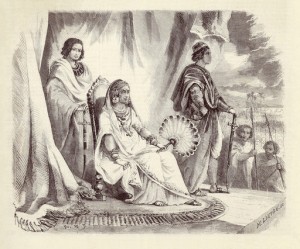

Scramble for Africa 16: Female Caligula DESTROYS Madagascar!

Clickbait title aside, this episode continues to follow the French as they Scramble for Africa. In this case, how France managed to steal the enormous island of Madagascar from its powerful African rulers. We of necessity do tell the story of Queen Ranavalona, but also the outrageous deeds of the French military, the dastardly things they said, and some of the rebellions of the Malagasy that started straight away and continued until independence, including the menelamba movement aka the Rising of the Red Shawls.

In Real Time with Stan Cox 1: The US environmental and political crisis

We have hatched a new plan for a series on the Anti-Empire Project, a monthly discussion of (mainly) environmental issues with Stan Cox. Stan is the author of quite a few environmental books and is going to be writing a monthly dispatch about US politics and environmental movements moving into the next US presidential election. Each episode of the series we’ll talk about his latest dispatch, and conclude with some thoughts about anti-imperialism and environmentalism. We start this one with an introduction to the series and what you can expect from it.

Anti-Empire Radio 108: Pakistan – I think it was a coup!

Was Imran Khan ousted in a US-backed regime change, or is Imran Khan crying conspiracy over a routine non-confidence vote? Was the memo real or exaggerated? Are the mass protests a sign of a cult-like following or a repudiation of a sleazy change of power? Was Imran Khan not a part of the very establishment that just threw him out? What will be the implications for Pakistan’s relationship with China? For Afghanistan? I discuss these questions with journalist Waqas Ahmed.

AER 107: Interviewed by the Cadre Journal about the DR Congo and Rwanda

A new youtube channel, the Cadre Journal, has been publishing hour-long in-depth interviews with Communist party activists and others on and largely from the Global South. I was happy to be invited on to talk to them about the history of the US in the DR Congo and Rwanda. Check out their channel – they’re doing an interview a day almost, and they’re all really good.

Scramble for Africa 15: France Seizes West Africa

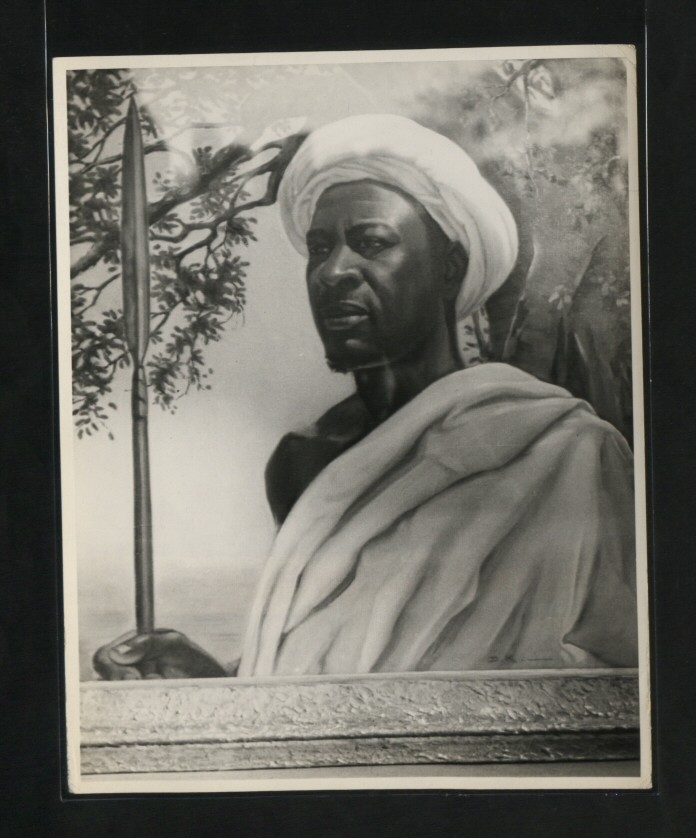

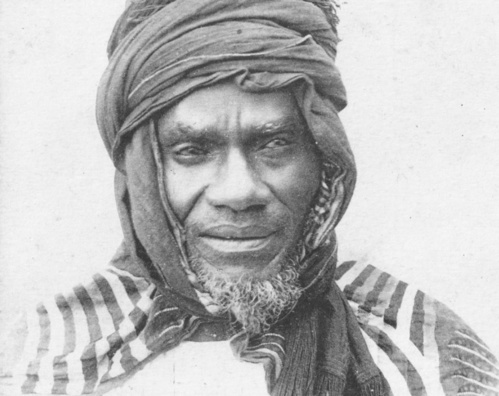

In this episode France seizes the territories of the Tukolors (overthrowing Sultan Ahmadu), battles Samori Toure, and fights a long war with King Benanzin of Dahomey. Some observations about the differences between France’s notions of colonialism and those of the British, in whose footsteps the French colonizers hoped to follow.