I was a guest on the fantastic podcast, In the Context of Empire, where I spoke with co-host Matt McKenna about lots of things, but mainly about how imperialist propaganda works.

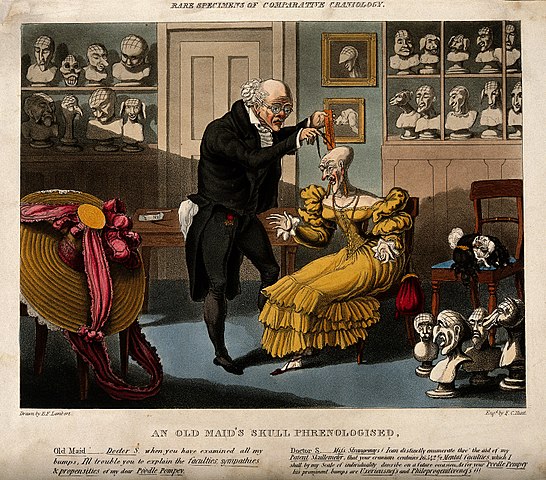

Civilizations 33b: Scientific Racism

The old saying goes that Science ain’t an exact science, and nowhere is that more true than with the Scientific Racism of the 19th century. From its predecessors in the 18th century, we get into the unholy trinity of Pearson, Galton, and Fisher. We talk about craniometry, phrenology, IQ testing, “race development” (now called International Relations), and racism in all your favorite fields, from criminology to anthropology, to political science and economics, to sociology and statistical science itself. We talk about the history, so you can ponder the question: has science moved past all this racist baggage?

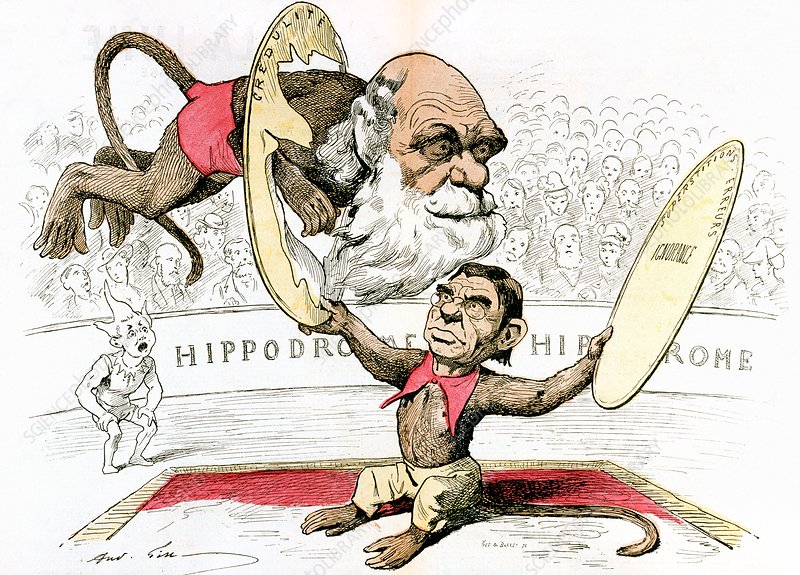

Civilizations 33a: Darwin and 19th century scientific advances

Charles Darwin’s book On the Origin of Species was read by Lord Elgin before he burned down the palace in Beijing and by Marx, who was so excited he asked Darwin if he could dedicate a volume of Capital to him (Darwin politely declined, not wanting to offend religious sentiment). We talk Darwin and the debates he spawned, physics, Freud, and about the scientific advances and missteps of the late 19th century. Part 1 of a series on Science, Scientific Racism, and Racism in the 19th century.

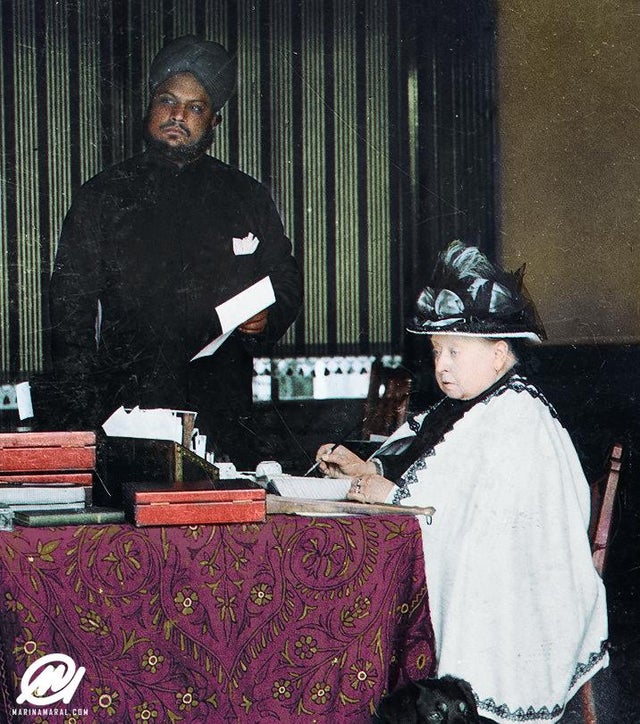

Civilizations 32: Still a bit Victorian, aren’t we?

Racism, imperialism, repression of sexuality, hypocrisy, pugilism, world fairs, parades, animals on display, worship of a royal family… we look at the Victorian era and the Queen herself. Good thing we’ve come so far since those days… right?

AEP 80: My comments on The Arrest of Meng Wanzhou and the New Cold War on China

On March 1, I was on a panel hosted by the Hamilton Coalition to Stop the War, the Canadian Peace Congress, World Beyond War, the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute, and Just Peace Associates. The topic was “the Arrest of Meng Wanzhou and the New Cold War on China”. Other panelists were Radhika Desai, William Ging Wee Dere, and John Ross – all of whom covered different aspects of the situation. I focused my remarks on Canada’s own record of genocide and racism, summarizing some of what we’ve been talking about in recent Civilizations episodes. The whole panel is out there on youtube – this audio is just my talk, 17 minutes long.

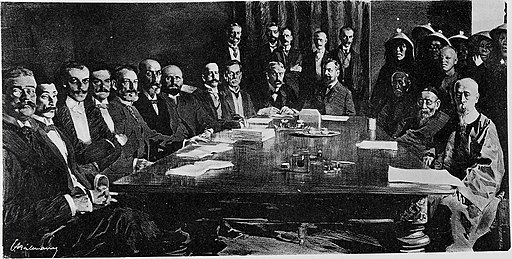

Civilizations 31: The first anti-imperialist uprising of the 20th century: Yi Ho Tuan, or Boxer Rebellion of 1900

By pure coincidence, we are publishing this episode on the day the world contrasted the the Alaska Summit – a US-China meeting in March 2021, in which China told the US to stop posturing, to the humiliations of the Boxer Protocol of 1901. In this episode, we talk about the terrible famines of 1876 and 1896 in China and India that killed tens of millions of people, the context of the Boxer Uprising of lightly armed but tenacious anti-imperialists, and the further humiliations inflicted on China by the imperialists at the nadir of China’s century of humiliation.

India’s Right-Wing Government Is So Hungry for Profit It Will Risk a Famine for the Country

Justin Podur, for Globetrotter

India’s right-wing government has been deploying all the modern tools of repression against a historic farmers’ protest. Much is at stake. For the people of India, their agricultural system is about to get far more precarious. For its farmers, ruin, and bankruptcy for millions, is all but guaranteed. For the government of Narendra Modi and his elite backers, it’s a crossroads moment; they calculate that their political power is assured for decades if they can refashion the politics of rural India and force dependency upon the farmers.

The farmers are protesting because the three farm bills, which were passed by the central government in September 2020, will dismantle the state-run agricultural procurement system in Punjab and Haryana, the breadbasket states of India.

In its defense, the Modi government has simultaneously claimed that the bills will enable a great modernization and also that nothing will change; the billionaires who will benefit (Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries and Gautam Adani’s Adani Group) have denied having any interest in entering the newly privatized business.

The billionaires have been set loose in the henhouse. As Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty from the World Inequality Lab at the Paris School of Economics reported, India’s top 1 percent in today’s “Billionaire Raj” have a similar share of the national income as the top 1 percent did under the British Raj.

The “Billionaire Raj” is preparing to turn India back from a country of hunger (on the 2020 Global Hunger Index, India is 94th out of 107 countries) to a country of famine.

Agrarian Crisis Rooted in British Colonialism

The roots of India’s agrarian crisis are far deeper than the three new laws. The seeds of the agrarian crisis were planted in the soil of British colonialism.

Precolonial India was characterized by historian H.H. Khondker in 1986 as a moral economy, a “social arrangement which guarantees a minimum subsistence for all.” In Mike Davis’ book Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, he argued that “Mogul India was generally free of famine until the 1770s. There is considerable evidence, moreover, that in pre-British India before the creation of a railroad-girded national market in grain, village-level food reserves were larger, patrimonial welfare more widespread, and grain prices in surplus areas better insulated against speculation.” The Mogul state “regarded the protection of the peasant as an essential obligation,” relying on “a quartet of fundamental policies—embargos on food exports, antispeculative price regulation, tax relief and distribution of free food without a forced-labor counterpart—that were an anathema to later British Utilitarians.” The Marathas, another major pre-British power in India, forced local elites to feed the hungry during famines. The British were horrified, calling this the “enforced charity of hundreds of rich men.” The Sikh Empire ruled in Punjab, where many of the protesting farmers are from. Its rulers enacted land reforms even while fighting the Mughals and the British.

Then the British East India Company took over the collection of revenues in Bengal, and the British Empire spread its tentacles across the subcontinent.

Historian Navyug Gill summarized the British system as follows in an article in Outlook Magazine: the British introduced “caste-based private property, the tethering of revenue demands to cash payments, and embedding agriculture within global circuits of production and consumption… [A]ctual harvests no longer corresponded to taxation rates, and fluctuations in commodity prices meant drastic swings between modest prosperity and widespread impoverishment. A bumper crop could be rendered worthless by uncontrollable forces in far-off parts of the empire, and yet the revenue would still have to be paid. The bane of those who became peasants was being at the mercy of the state as much as the seasons.”

The commodification of food followed—and so did famine.

Providing insights about the extent of famines in India under the British rule, Davis’ book highlights that “[a]lthough the British insisted that they had rescued India from ‘timeless hunger,’ more than one [district] official was jolted when Indian nationalists quoted from an 1878 study published in the prestigious Journal of the Statistical Society that contrasted 31 serious famines in 120 years of British rule against only 17 recorded famines in the entire previous two millennia.” The British imposed new humiliations: “Requiring the poor to work for relief, a practice begun in 1866 in Bengal under the influence of the Victorian Poor Law, was in flat contradiction to the Bengali premise that food should be given ungrudgingly, as a father gives food to his children.”

As H.H. Khondker noted, British writer W.H. Moreland in the 1923 book From Akbar to Aurangzeb “made a distinction between” “work famines” under British imperialism and precolonial “food famines.” During the pre-imperialism period, people starved because of actual food shortages. Under imperialism, people starved because they were poor, had no employment, and therefore couldn’t be fed under a Victorian morality that said you couldn’t get something for nothing.

An Economist article published in 1883, which was quoted in Dan Morgan’s 1979 book Merchants of Grain: The Power and Profits of the Five Giant Companies at the Center of the World’s Food Supply, stated, “A good wheat harvest is still as much needed as ever to feed our closely packed [British] population. But it is the harvest already turning brown in the scorching sun of Canada and the Western States—the wheat already ripe in India and California, not the growth alone of the Eastern counties and of Lincolnshire, that will be summoned to feed the hungry mouth of London and Lancashire.”

Mass death through starvation was the price of enabling the British Empire to build a truly global, militarized economy in grain, under which agriculture in all reaches of the globe could serve imperial designs and food itself could become a weapon. Food insecurity for the colonies purchased food security for the metropole.

German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht once wrote, “Famines do not simply occur; they are organized by the grain trade.”

Development experiences between India and China are often compared and can be useful here as well.

Pre-colonized China was even better organized than Mughal India. Before the 1839 Opium War, China under the Qing dynasty “had both the technology and political will to shift grain massively between regions and, thus, relieve hunger on a larger scale than any previous polity in world history,” as Davis explained in Late Victorian Holocausts.

Imperialism in China led to famine there too, the largest of which occurred in 1876. The multiple Opium Wars, which forced the Chinese government to pay massive reparations to its invaders and plunderers, shattered the old food security system. The state “was reduced to desultory cash relief augmented by private donations and humiliating foreign charity,” Davis wrote.

In both India and China, the years of imperialism—the commodification of grain—condemned tens of millions to death by starvation.

Food Security in Independent India and China

Post-Independence, newly sovereign India and China both attempted to get their countries back on the path of food security. Both efforts had initially disastrous results. China had a severe post-Independence famine from 1959 to 1961, worse even than the ones under imperialism. China corrected this trajectory and went on to eliminate hunger and, in 2018, to eradicate poverty as well, as reported at the time by Chinese writer Qin Ling and in Robert Lawrence Kuhn’s documentary film “Voices from the Frontline: China’s War on Poverty,” which was initially aired on PBS before being pulled in May 2020.

In stark contrast with China, India did not have a famine since Independence, but has tolerated chronic hunger. In the most famous comparison of the two countries, economists Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen wrote in their 1991 book Hunger and Public Action that:

“Comparing India’s death rate of 12 per thousand with China’s of 7 per thousand, and applying that difference to the Indian population of 781 million in 1986, we get an estimate of excess normal mortality in India of 3.9 million per year. This implies that every eight years or so more people die in India because of its higher regular death rate than died in China in the gigantic famine of 1958–61. India seems to manage to fill its cupboard with more skeletons every eight years than China put there in its years of shame.”

India’s National Family Health Survey for 2019-20 showed that in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state of Gujarat, sometimes touted as an economic model, 39 percent of children under the age of five have had their growth stunted by malnutrition. The report is full of similar achievements, state-by-state, by the current Indian government. Approximately 25 percent of all hungry people live in India, where around 195 million people are undernourished. Thousands per day, perhaps a million per year, die of malnutrition in India, most of whom are children.

A majority of the population lives in poverty.

India’s Flawed Agrarian System

Navyug Gill outlined the limited nature of India’s post-Independence agrarian system in his article about the roots of the farm bill demonstrations. “[W]hat was put in place from the 1950s onwards was a system of rules, quotas and regulations meant only to minimize the worst of colonial depredations. The purpose was to mainly fulfil the growing needs of a famine-stricken country while bringing about a modicum of stability for landholders of varying sizes. In other words, the state modified and re-directed rather than transcended the tensions among national food supply, capitalist imperatives and rural wellbeing.”

Let’s go into the details of these measures, using several interviews conducted in different media with agriculture researcher Devinder Sharma as our source material.

From India’s independence in 1947 until the mid-1960s, India was dependent on food aid from the United States’ PL 480 program. The Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) were established in the 1960s with the intention of getting India off of this dependence on U.S. food aid. The system was built in tandem with the U.S.-sponsored Green Revolution, which sought to use capital-intensive, high-tech, high-input techniques to increase yields. The danger was that in the absence of such a system, higher yields would lead directly to a crash in agricultural prices, the ruination of farmers, and a British Empire-style cycle of disaster.

Two pieces were put in place to protect against this. First, government-run markets, the so-called “mandis,” were set up where the government would purchase the farmers’ grain at a guaranteed price (which would later be called the “minimum support price,” or MSP) if the private sector could not. Second, the government, through the Food Corporation of India (FCI), would “mop up” the surplus production in bumper crop years and move that grain to deficient areas through the public distribution system. The system worked: the Green Revolution yields did indeed materialize. The mandis raised enough in taxes to fund not only the market infrastructure but also a network of village roads and certain rural development funds. Dependence on PL 480 grain was broken. And there were no more famines.

There were, however, flaws with the system. First, as environmental activist Vandana Shiva documented, the environmental effects of the Green Revolution rendered it unsustainable in the long term. Second, environmental unsustainability was matched by financial instability; the imported American model of the Green Revolution was based on saddling farmers with impossible levels of debt.

There were also limitations, including a gap in procurement, as Sharma explains: despite the announcement of the MSP for 23 crops, only two (wheat and rice) are actually procured by the government—and without actual government procurement, the mere announcement of an MSP is meaningless. Infrastructural limitations also reduced the system’s effectiveness, as Sharma goes on to say: the goal was for farmers to have access to a mandi within 5 kilometers, which would have meant setting up 42,000 mandis. But in more than 50 years, only 7,000 mandis have been established.

The result of these limitations is that only 6 percent of farmers access the minimum support price (MSP), while 94 percent are dependent on the market, explains Sharma during an interview with Newsworthy. The fact that so few farmers access the MSP is used by government proponents to argue that the farm bills are removing the last fetters on an efficient market. But, Sharma asks, while quoting figures from the National Crime Records Bureau, if the market system is so good for India’s farmers, why have 364,000 of them committed suicide since 1995? Why do farmers want an assured—and higher—MSP? The analogy with the labor market is clear enough—if the labor market were as good as free-market proponents claim, why would there be a need for a minimum wage, much less unemployment insurance?

The private buyers who want to get into the government business have promised that farmers would get higher prices than the MSP from them. Devinder Sharma asked during his interview why they would have any objection at all to a minimum support price, if they planned to pay more. He points out that the state of Bihar, which did away with its APMC system in 2006, sees farmers trucking wheat and rice into Punjab and Haryana to sell at the (now threatened) minimum support price guaranteed in those states.

The APMCs are accused of being government middlemen, Sharma notes. But the biggest fortunes in the world are already being amassed by middlemen “wearing a tie and a suit,” from Walmart to Amazon, who want “to replace the traditional middlemen” the government has acted as. India’s super-rich, Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani, are the picture of the American-style, well-connected, monopolist middleman. If the farm bills are not repealed, the new private grain trade will fall into their laps.

Years ago, Canadian agricultural economist Ian McCreary did a study of the Indian food procurement system. In an interview on February 6, McCreary told me that after crunching three decades of numbers, he found the Indian system to be “quite successful in its objectives” of providing stable prices and food security. The government assumed the financial risks, of which there were several. On the one hand, low international prices combined with a bumper crop at home would see India trying to store grain (expensive in India) or export at a loss. On the other hand, importing in a year when prices were high could get extremely expensive. But neither of these problems could be solved by privatization, as McCreary explained: “If the government wanted to contract out the storage, they could have done that within the structure of the current system.” And even after privatization, if prices rose to the point where millions of people couldn’t afford to purchase food, the government would still be responsible for feeding them.

McCreary had concluded that extending government procurement at the minimum support price to pulse crops from drier and less productive regions would benefit both farmers and those who received food through the public distribution system. While he shared concern for the farmers, McCreary was also very concerned about the food security implications of the new farm bills. “Poor consumers are going to be very vulnerable in the event of international prices being driven up.”

The government weighs these implications against opportunities for Reliance and Adani to make profits in a new market. McCreary further said, “When you move from a situation where [the] market is controlled and prices operate within a defined range, to one where you’re exposed to the market, the players that buy and sell grain to arbitrage have [the] potential to make quite a bit of money.”

Privatization of Grain Procurement in Canada

India’s rulers look to the West for inspiration; but in fact, Western agriculture should be an inspiration to no one. The nightmarish consequences of privatized corporate agriculture are poorly understood by those who see only Western agriculture’s productivity and not its real social and environmental costs.

Take the example of Canada. The privatization of government grain procurement in India today under Narendra Modi is analogous to the privatization of the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) in 2012 under Canada’s right-wing former Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Established in 1935, the CWB was a farmer-run, farmer-funded marketing agency that worked through a “single desk”—private buyers had to buy from the Wheat Board and could not negotiate prices directly with farmers. Farmers earned more. Former National Farmers Union (NFU) president Terry Boehm estimated before the privatization that “Wheat Board marketing and single-desk selling bring hundreds of millions more dollars to farmers each year than they would receive in an open market.” Like India’s system, the CWB was privatized amid half-hearted murmurings about “increased economic opportunities” for farmers through a rapid and deceitful piece of legislation—in this case, called the Marketing Freedom for Grain Farmers Act. The elected board was dismissed, the assets turned over to their new owners, a joint venture called G3 Global Grain Group. Within two years of the privatization of the CWB, several of the grain companies increased their profits by billions.

Like the APMC, the CWB wasn’t perfect—some farmers no doubt had believed they would do better on their own, while others complained about a lack of transparency. These farmers, Boehm says, “now labor under a system dominated by multinational grain companies that disclose almost nothing.” Ed Sagan, another NFU member, did a back-of-the-envelope calculation and concluded that an average farmer has probably lost nearly half their income since the CWB was dismantled—a figure confirmed by multiple years of Statistics Canada reports. A chart produced by the union outlines many of the depressing new realities.

Meanwhile, the United States, Canada, and the EU are demanding India produce less locally and provide a bigger market for highly subsidized grain sourced from the metropole. Economist Prabhat Patnaik has noted that “diversification away from food grain production and importing food grains instead from imperialist countries has been a demand of the U.S. and EU for quite some time.”

Looking Beyond the West for Solutions

Neither Canada nor the United States offers any kind of model for agriculture. In the United States, farm incomes are on a continuous decline, and rural suicides are on a continuous rise. Throughout Europe and North America, agriculture is heavily subsidized, with the average U.S. farm receiving subsidies of tens of thousands per year ($61,286 in support per farmer, compared to $282 per Indian farmer, by one estimate). Indian farmers have the suicides, but they will never have the subsidies, nor will they have a fraction of the land per farmer that North American and European farmers have.

The development advice given to developing countries by the IMF and World Bank for the past several decades has been to depopulate the countryside and move the people into cities. People have moved. They were living in cities at the edge of survival, and when COVID-19 hit, they found themselves unable to survive there, leading to the largest urban-to-rural migration in human history. But more than half of the people of India still make their livelihoods from agriculture, which receives a public sector investment of 0.4 percent of GDP (compared, as Sharma points out in an interview with Enquiry, to 6 percent of GDP in tax concessions to the corporate sector annually, a number that has only grown with recent corporate tax cuts).

So what could be done? China recently eliminated rural poverty, but there is little in China’s recent experience, with dedicated government and party cadres helping individual rural families with income-generating and income-supplementing initiatives, that India can emulate.

But there is no reason India couldn’t find its own way to eliminate poverty. There is much that could be done, starting with Sharma’s suggestions: The minimum support price could be extended to more crops, the price raised, and the number of mandis increased to reach the one-per-5-kilometers goal. The state of Kerala has set a minimum price of 20 percent above the cost of production for vegetables—and the prices end up higher than they announce. In PM Modi’s own state of Gujarat, there’s a very successful dairy cooperative called Amul. The cooperative model could be fruitfully extended to provide better livelihoods for farmers. Between work produced by national commissions, peasant movements, economists, and policy analysts, Navyug Gill has pointed out that “real alternative solutions are actually not hard to come by.”

As so often occurs in our neocolonial world, it is the colonial baggage that must be discarded. Once it is, solutions present themselves in abundance.

This article was produced by Globetrotter. Justin Podur is a Toronto-based writer and a writing fellow at Globetrotter. You can find him on his website at podur.org and on Twitter @justinpodur. He teaches at York University in the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change.

Civilizations 30: Korea’s Dilemmas from Donghak Uprising to Sino-Japanese War 1894

By the 1860s it was Korea’s turn to face the dilemma of how to deal with the imperialists. Qing China and Meiji Japan had a lot to say about what they thought Korea should do. We talk about the attempts to reform, Donghak Uprising in Korea, and the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5.

AEP 79: Sorry for using the word “Corbyn” (in Canada)

I’m joined by Nora Barrows-Friedman and Asa Winstanley, both of the Electronic Intifada podcast. We’re piecing together the story of how lifelong anti-racist Jeremy Corbyn of the UK Labour Party was taken down by a smear campaign, which began by targeting those around him. Having taken him down, the smear campaign continued and managed to force AOC in the US to apologize for talking to Corbyn on the phone. The campaign has moved to Canada, where NDP MP Niki Ashton has been dragged by media and by her own party for daring to host an event with a fellow left-wing politician from the UK. We analyze the nature of the attack, look at cases including Corbyn, AOC, Ilhan Omar, Marc Lamont Hill, and now Niki Ashton, and speculate about what the best strategy might be for self-defense for those who believe in solidarity with Palestinians.

Civilizations 29: Japan joins the imperialists, 1853

India had Plassey in 1757, China had Opium War 1 in 1839, and Japan had Commodore Perry’s visit in 1853. After centuries of keeping the imperialists at bay, Japan found them knocking down the gates. And in a series of events studied by everyone in Asia but never imitated, Japan went from having a brief colonial encounter to joining the imperialists within a few decades. We don’t know if anyone can tell you why it happened, but we can tell you what happened, on this episode of Civilizations.