There is no case of nonviolent anticolonial struggle

The US struggle for civil rights, remembered as the nonviolent movement of Martin Luther King, was also the movement of the Deacons for Defense in Louisiana, the movement of the Mississipi Regional Council of Negro Leadership which could “speedily mobilize substantial and deadly firepower” including E.W. Steptoe who had “guns all over the house, under pillows, under chairs”, of Robert Williams of Monroe, North Carolina’s NAACP who said in 1959 that “we must be willing to kill if necessary”, the movement of a night-long battle with police in Albany, Georgia in 1962 and in Birmingham, Georgia in 1963, when “every day of riots was worth a year of civil rights demonstrations”.

The Indian Freedom struggle, remembered as the nonviolent movement of MK Gandhi, was also the movement of the Hindustan Republican Army, of Chandrasekhar Azad and of Bhagat Singh, of the Telengana Uprising of 1946, of the Tamil Nadu anti-feudal struggle of 1943, of the underground guerrilla struggles after Quit India in Odisha, West Bengal, Bangalore and elsewhere, of the Toofan Sena in Maharashtra, of Indian National Army of Subhas Chandra Bose, and of the Naval Mutiny of 1946.

The two most iconic tales of the deployment of strategic nonviolence turn out, upon historical examination, to have been armed struggles, replete with violence.

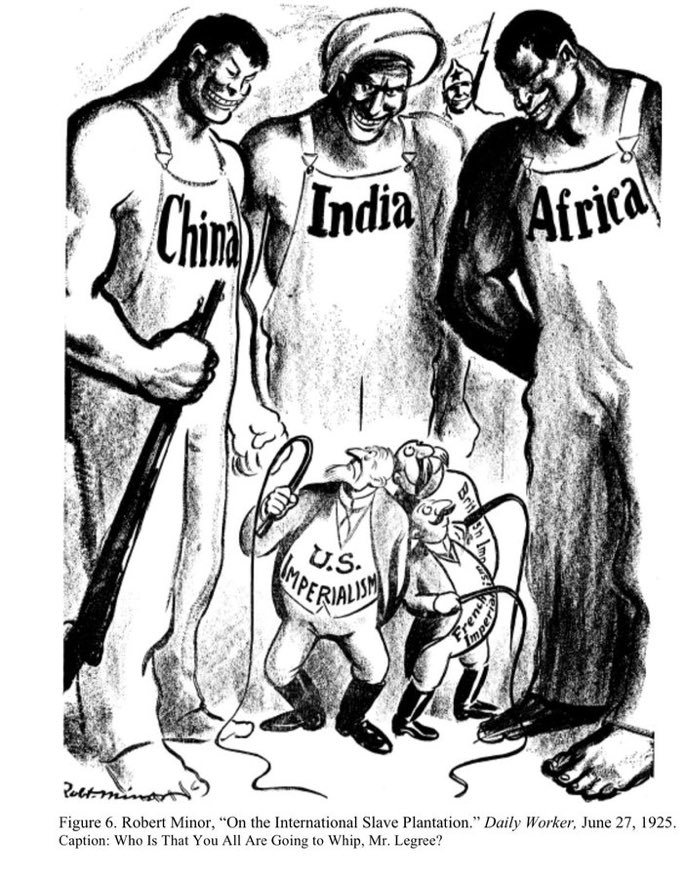

Through an analysis of the work of Gene Sharp (“Gene Sharp’s Neoliberal Nonviolence” part 1 and part 2), writer and academic Marcie Smith has revealed the existence of a sort of “nonviolence industrial complex”, a network of institutions linked to the US foreign policy establishment, dedicated to two things: 1. steering opposition to US-backed states and projects in nonviolent directions, and 2. to using methods of nonviolent insurgency as a part of a set of tactics (including covert, violent action) to destabilize US targets.

The jewels in the narrative crown of this nonviolence network are the US civil rights movement and the Indian Freedom Struggle, which is why I devoted the two previous articles in this series to showing that these were in fact armed struggles.

The narrators of the nonviolence network have one other weapon: quantitative analysis. But this weapon too, turns out to be a plastic replica.

In their book Why Civil Resistance Works, Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan claim to have proven through statistical analysis that nonviolence is more effective than violence. Their analysis is worth detailed examination since it claims to have the authority of a huge dataset and logistic regression proving the chances of success are higher with nonviolence.

But what did they actually do? They made a list of several hundred revolutions from the 20th century (nearly all of which were in fact violent), coded some struggles as violent and others not, coded some struggles as successful and others not (in fact many of the successes delivered the countries and their economies directly over for imperialist plunder), and then after a quantitative assessment which amounts to counting the number of successful cases of each type, found that their “nonviolent” coded struggles had a higher chance of success. These nonviolent-coded struggles include:

- the South African struggle (including its armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe);

- and the many East European color revolutions.

- the Palestinian Intifada;

A quick skim of any of these histories show that these were all violent struggles. The data reveal the conclusion the authors believed at the outset and for which they coded their data. Why Civil Resistance Works is historical falsification covered with a quantitative mystique.

To determine the veracity of their analysis we need examine only those events coded as both nonviolent and successful. Nonviolent failures are of no interest, since they do not bolster the nonviolence narrative. Neither violent successes nor failures are of interest either, since to the nonviolence industry armed struggles are already failures.

The database published with the book contains 57 nonviolent successes. There are two types of movements analyzed in the database: movements for regime change and movements for secession. There are no nonviolent successes for secession movements: all 57 nonviolent successes are regime change successes. There are only 4 secession successes out of 46 attempts in the database (Croatia, Tigray, Bangladesh, and Aceh from Indonesia starting in 1976-2005). All of these were violent.

Philosophers of science know that there is a complicated set of human decisions that go into the translation of things occurring in nature into statistical data. Even such decisive phenomena as birth and death can only be entered in a spreadsheet as “0” and “1” by the declaration of a doctor. Of all the types of data to translate into “0”s and “1”s on a spreadsheet, historical data is the worst. Was the French Revolution a success, a failure, or is it too early to tell? In history, some failures are necessary prerequisites for future success; some processes simply cannot be classified as one or the other (Chenoweth and Stephan include a “limited success” category to try to capture these).

The relevant point here is that the coding of these 57 events as both “nonviolent” and “successful” ranges from deeply problematic to utterly preposterous.

Going through them:

In this database, the Palestinian liberation struggle apparently started in 1973, was violent, and a failure. The Intifada, 1987-1990, is considered a nonviolent partial success. The 1979 overthrow of the Shah of Iran, which I won’t dispute was successful, is coded as a nonviolent process – which would be a surprise to the guerrilla fighters and defectors who fought the Shah’s soldiers in the streets. The 2005 Cedar Revolution in Lebanon is coded as a success, but it did not change the regime and Lebanon’s political system continued as before.

The Cedar Revolution is not the only “color revolution” (short-hand for a US-backed regime change operation in a US enemy country led by US-trained political and media cadres) coded as a nonviolent success. Indeed a good part (14 of the 57) of the nonviolent successes are East Europe color revolutions: 1989 Germany, 1981 Poland, 1989 Hungary, 1989 Czech, 1989 Slovakia, 1989 Bulgaria, 1990 Russia, 1989 Estonia, 1989 Latvia, 1989 Lithuania, 2001 Ukraine, 2003 Georgia, 1989 Kyrgystan, 2005 Kyrgistan. In the background of all of these color revolutions was the threat of US-led NATO expansion and US nuclear war, as well as the fact of US violent covert operations. Three more of these East Europe nonviolent successes – 1999 Croatia, 2000 Yugoslavia, 1989 Slovenia – are from the incredibly violent US-led dismembering of Yugoslavia in a series of civil wars (described in, e.g., Michael Parenti’s book To Kill a Nation and Diana Johnstone’s book Fool’s Crusade).

In Africa, in addition to coding the South African anti-apartheid struggle as nonviolent (which would be news to umKhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress), and the Ghanaian, Zambian, and Malawi Independence struggles as nonviolent (they were not), the majority of African nonviolent successes in the database were mass mobilizations to press for elections. These were: 1989 Mali, 2000 Ghana, 1993 Nigeria, 2001 Zambia, 1992 Malawi, 1991 Madagascar, 2002 Madagascar, 1985 Sudan (in active civil war at the time).

In East Asia, the 1960 April Revolution in Korea (in which 186 people were killed) is coded as a nonviolent success, as is the 1986 People Power Revolution in the Philippines (after decades of guerrilla struggle and notable defections from the military). East Timor, widely recognized to have suffered a genocide from the 1970s to the 1990s, is coded as having had a nonviolent success in 1988, despite Independence coming in 1999 after a long guerrilla war. A 1973 popular uprising in Thailand, that had bomb explosions and dozens of deaths in riots, is coded as a nonviolent success. So, too, in Thailand, a long-running political crisis in 2005 that culminated in a military coup in 2006, is coded as a nonviolent success.

In the Americas, the database includes as nonviolent successes a 1931 naval mutiny in Chile, a 1944 armed revolution in Guatemala, 1958 Venezuela (which featured attacks on security services headquarters and resulted in the awful Punto Fijo pact), a clear failure to overthrow the system in Mexico in 1987, and struggles against dictatorships in Argentina (1977 and 1986), Uruguay (1984), and Chile (1983), all of which had prominent guerrilla movements. The database cites 2002 in Venezuela as a nonviolent success, but there were two things that happened in April 2002 in Venezuela: a violent coup against Chavez and its reversal when the army refused to endorse the coup: the coup failed, the the successful reversal of the coup involved military moves.

In Europe, a 1974 military coup in Portugal is coded as a nonviolent success. Of the churning conflicts, revolutions, and civil wars in Germany in the 1920s that culminated in the rise of Nazism in the 1930s and the most violent events in human history so far, 1923 in Germany is coded as a nonviolent success.

There is, however, a specific type of conflict coded as a nonviolent success in the database that recurs in different parts of the world, in which a spent dictatorship gives way, in the face of a basically nonviolent popular movement, to an election. About eight of the 57 nonviolent successes belong to this pattern: 1963 and 1974 in Greece, 1977 in Bolivia, 1984 in Brazil, 1985 in Haiti (which led to a military coup and additional years of mobilization until Aristide was elected, then violently overthrown again…), 1990 Guyana, 2000 Peru, and 2001 in the Philippines. This particular set of eight cases (five of which took place in the Americas) could be used as evidence for the argument that, under the right circumstances, largely nonviolent popular mobilization can reverse a stolen election or force a weakened government to agree to elections. It does not prove at all that nonviolent movements have a better chance of success than violent ones. But even in these cases, the threat of violence existed.

There is value in analyzing and comparing movements of resistance in history. There may even be value in coding them and calculating probabilities. But there is no value to be had in building a model for probability of success based on violence and nonviolence by miscoding failures as successes and armed struggles as nonviolent.

We never needed a database to tell us that under some circumstances a social and political struggle can be kept on the nonviolent plane. The key factor is the investment elites have in maintaining the policy that is being challenged. Union struggles can often succeed in winning wage and working conditions improvements nonviolently. Every election where the loser congratulates the winner and there is a peaceful transfer of power is an example of a successful nonviolent struggle. But colonialism, struggles over land, in which oppressors have racial ideas of superiority over the oppressed? In these cases, whether it succeeds or fails, armed struggle alone has a chance. Only by wielding falsified histories and models can the nonviolence storytellers argue otherwise.

Palestine 2018: the final proof of the uselessness of nonviolence in anticolonial struggle

And so we turn to Palestine, a colonial struggle over land, in which the oppressors have racial ideas of superiority over the oppressed and are, since 2023, engaging in active genocide. Palestine has been an area of focus for the nonviolence industry for decades.

A February 2024 paper by the Center for Constitutional Rights has shown that US anti-terror legislation was “driven by anti-Palestinian agendas from the beginning.” The nonviolence industry has had a similar Palestine focus from the beginnings of Gene Sharp’s Albert Einstein Institute. The 1987-1989 Intifada was an object of fascination for Sharp and for the nonviolence industry. Sharp’s Journal of Palestine Studies article in 1989, “The Intifadah and Nonviolent Struggle”, identifies him as the author of the 1973 book The Politics of Nonviolent Action as well as the author of Almuqawama Bila Ounf (Nonviolent Resistance), published in Jerusalem by the Palestinian Center for the Study of Nonviolence in 1986. In the article, Sharp argues – quantitatively again – that 85% of the intifada has been nonviolent. He simply asserts that armed struggle and nonviolent struggle are “not easily mixed to advantage” – and so the Palestinians should go from 85% to 100% nonviolent. After the usual arguments absolving Israelis of responsibility for the violence they mete out on Palestinians and the normal nonviolence argument that the the colonial repression faced by the victims is their fault for provoking their oppressors, Sharp suggests Palestinians go on a 21-day hunger strike, followed by “whistling or wailing at night, especially in dark streets” and “having the youths standing peacefully, not fleeing, holding small Palestinian flags, their right hands outstretched in a gesture of friendship.” Sharp dangles recognition before well-behaved Palestinians: “The shift to fully nonviolent struggle would also make possible more active support for Palestinian independence in Western Europe and the United States.”

After months of genocide, starvation, and the gleeful mass murder of tens of thousands of children, all filmed and celebrated across Israeli society and by Israel’s supporters in the West, Sharp’s arguments are striking for their absurdity as well as their vulgarity.

But Sharp was not alone.

Pakistani activist and academic Eqbal Ahmed made the argument to Palestinians numerous times. He reported to journalist David Barsamian in 1996 (published in the 2000 book Confronting Empire) that he’d told a group of Arab students in the US after the 1967 war that “armed struggle was supremely unsuited to the Palestinian condition,” that “Israel’s fundamental contradiction was that it was founded as a symbol of the suffering of humanity at the expense of another people who were innocent of guilt,” and that “you don’t bring (the contradiction) out by armed struggle. In fact you suppress this contradiction by armed struggle.” He told them in 1968 that

“This is a moment to fit ships in Lebanon and say, ‘we’re not going to destroy Israel. That is not our intent. We just want to go home.’ Reverse the symbols of Exodus. See if the Israelis are in a mood to sink some ships. They probably will. Let them do so. Some of us will die. Let us die.” Eqbal Ahmed imagined if Arafat were to “take on the role of a Gandhi or a Martin Luther King and announce tomorrow, ‘I must stop these settlements. They violate the spirit of Oslo. We are committed to peace. You are making war. We do not want to use violence against you. Peacefully we will march against you. We will sit in. We will clog the roads, start a full-scale movement, and discipline the Palestinians not even to throw stones, intifada-style, because Israelis will use and justify bullets against stones. They will use soldiers against children. Don’t even give them that.’ Israel will divide. It will divide as a society the way America divided. I would keep it divided until it makes peace.”

But Eqbal Ahmed, despite being an insightful anti-colonial strategist, was wrong about the histories he cited (Gandhi and Martin Luther King) and wrong about what would happen in the face of Palestinian non-violence, which did not divide Israel but incited Israel to ever-more intense racism.

Norman Finkelstein wrote a whole book (What Gandhi Says) trying to assimilate lessons from Gandhi to the Palestinian struggle. His conclusions are ambivalent to say the least, since at times he writes things like “it might fairly be said that Gandhi fostered a death cult.” The book ends up being a presentation of the self-contradictory politics in Gandhi’s writing, not the practical manual of civil resistance Finkelstein may have hoped to create when he picked up Gandhi’s 100 volumes of writing as an aid for the US-based academic and activist “to think through a nonviolent strategy for ending the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands.”

Palestinians took up these ideas in good faith for years – in better faith than the method deserves. Hundreds of Palestinians died trying to do nonviolent struggle. So too did a handful of friends of Palestine, including Rachel Corrie, Tom Hurndall, and others in the International Solidarity Movement.

Eqbal had suggested finding out “if the Israelis were in the mood to sink some ships.” They were – they already had been in 1967, if we count the USS Liberty – but in 2010 a nonviolent flotilla tried to go to Gaza*. Israel boarded the ships, killed some of the activists, and arrested, mistreated, and deported the rest.

But the culmination of the nonviolent vision, the maximum horizon of all nonviolence, the controlled scientific experiment of perfect nonviolence, occurred in the Great March of Return in Gaza in 2018. It proved that nonviolence does not work. From a scientific standpoint, the nonviolence debate ended in 2018.

As Gene Sharp’s article on the First Intifada opened the debate on nonviolence in Palestine, Jehad Abusalim’s article, “The Great March of Return: An Organizer’s Perspective”, in the same journal, closed the debate on the topic.

The Great March of Return started, Abusalim reports, with a facebook post by Abu Artema on January 7, 2018. Abu Artema asked, “What could the occupation bristling with arms do to a mass of human beings advancing peacefully? Kill ten, twenty, or fifty of them? And then what? What could it do in the face of an unwavering mass peacefully marching?” Abu Artema and others worked to make it happen and organized for months, calling for a date in March:

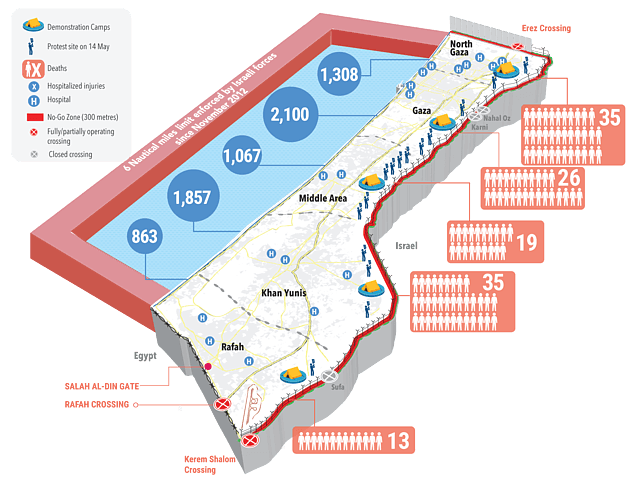

“To the surprise of all concerned, an estimated 30,000–45,000 people showed up on the first day of the Great March of Return. And on that day, Israeli snipers shot dead 17 Palestinians and injured some 1,400 others.32 The mainstream international media instantaneously referred to the carnage as “rioting” and “clashes” but to those on the ground in Gaza, it was beyond shocking: how could nonviolent protests unleash such fury as to cause Israel to kill 17 peaceful protesters and maim or injure another 1,400? That is how, from the very first day, bloodshed came to define the protest.”

By the end of the protest, cold-blooded Israeli snipers had killed 226 Palestinians and methodically injured 30,000. For the Israelis, it was sport. The Western media fluidly and easily lied about the march, its nature, and the murderous Israeli response. Neither Israel nor its sponsors faced any crisis or internal division about what they were doing to the Palestinians. Neither Israel nor the West paid any cost for inflicting these tens of thousands of Palestinian casualties.

Abu Artema, the protest organizer interviewed by Abusalim in the article, seems bereft of ideas at the end – he feels that more international mobilization is needed, some tool that prevents Israel from “targeting Palestinians in such a horrific way” and to “prevent the occupation from using propaganda to prime the public for slaughtering us.” The nonviolence industry was unable to come up with any such tools: the slaughter of Palestinians at the Great March of Return was not the fault of the nonviolent protesters any more than the genocide in 2023-24 was the fault of the Palestinian armed groups. Israel is a genocidal state: then as now, it is doing what it is organized to do.

Six years later, Palestinians are waging an armed struggle against the Israeli military in Gaza and the West Bank. The Israeli military has chosen to accept military casualties and defeats on the battlefield (including the methodical destruction of its armored vehicles and groups of soldiers) to focus entirely on conducting a genocide against Palestinian civilians, with the central goal being the destruction of all of Gaza’s hospitals and educational institutions and the murder of patients and medical personnel, while blocking food and water from reaching people. Palestinians’ allies in Lebanon, Iran, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen are all engaging militarily with Israel and its Western sponsors. In the region, for the time being, the nonviolence case is closed.

Back in America though, in the solidarity movement, with the expansion of campus protests in April 2024, along with police repression all over the US, the nonviolence debate will rise again.

Anti-genocide students demand universities – which turned out, to the surprise of the students and faculty, to be investment banks that sometimes teach classes – divest from the military industry feeding the genocidal state. The pro-genocide establishment has called the police to crush the protests. What will be the outcome? Nonviolent or violent? Success or failure?

*As I write this, another nonviolent international flotilla is planning to leave from Turkey to Gaza.