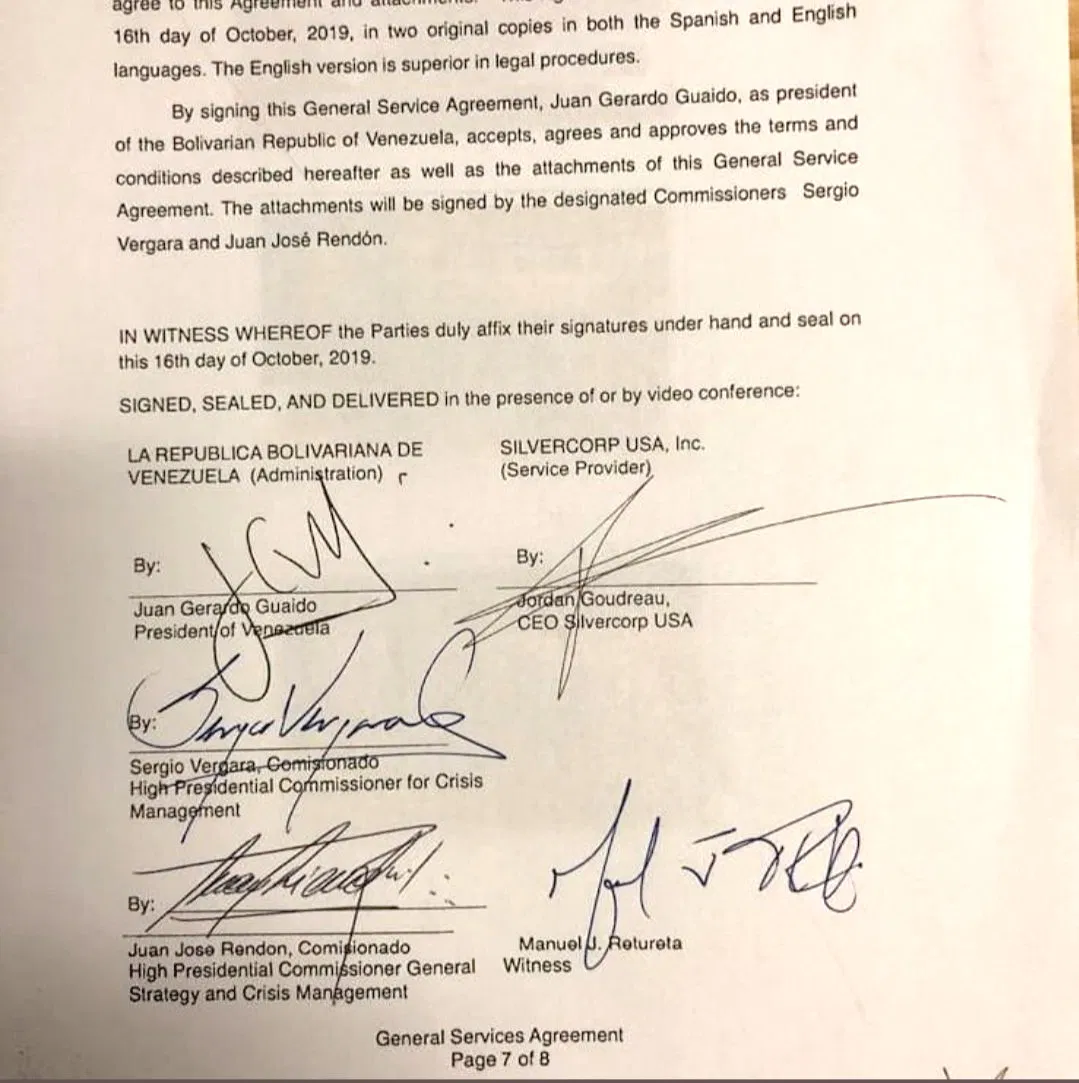

I talk to Maria Victor after the foiling of the May 3, 2020 terrorist plot against Venezuela, which involved the infiltration of American mercenaries by boat from Colombia. One of the mercenaries, Jean Goudreau of Silvercorp, gave an interview just before the attack where he revealed a signed contract with self-declared president Juan Guaido. We talk about this as the latest in a continuous run of coup attempts against Venezuela for the past twenty years.

Author: Justin Podur

The Brief 009: Hindutva Crackdown

India jails students, writers, and rights activists as the media works in effective coordination with the government inflaming sectarian divides, suppressing dissent and lionizing Modi. We speak to Shalini Gera and Freny Manecksha about India’s Hindutva crackdown.

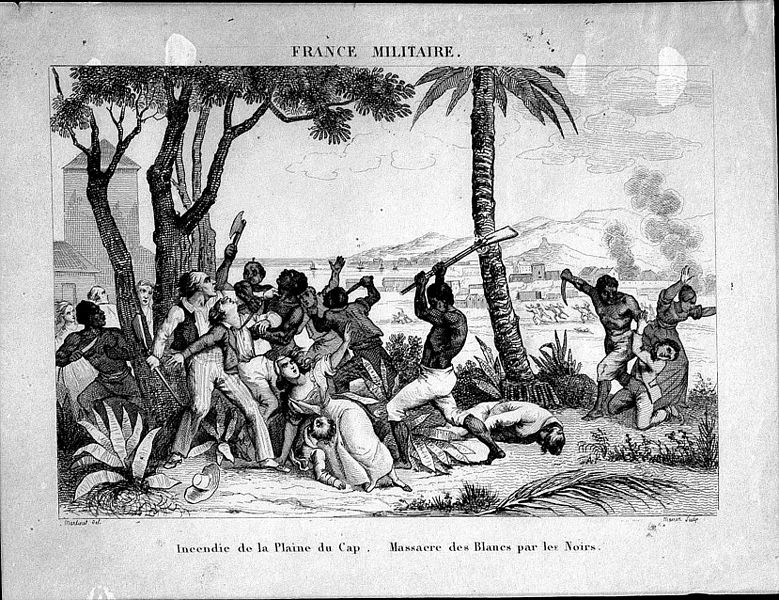

Civilizations Episode 6: The 18th Century Global Economy, aka slavery, genocide, and colonialism

The global economy was forged in the 18th century under European empires that committed genocides in the Americas and Africa, instituted mass slavery, and colonialism. This is the story.

Why most anti-bullying programs don’t work – and how to fight bullying – video

Civilizations Episode 5: The Bureaucracies of East Asia

Following Alexander Woodside’s book Lost Modernities, we talk about the Korean, Vietnamese, and Chinese Mandarinates, the peculiarities and pitfalls of a system based on competitive examinations, the interplay of meritocracy and feudalism, and the relevance of it all to today’s debates about standardized testing and education more generally.

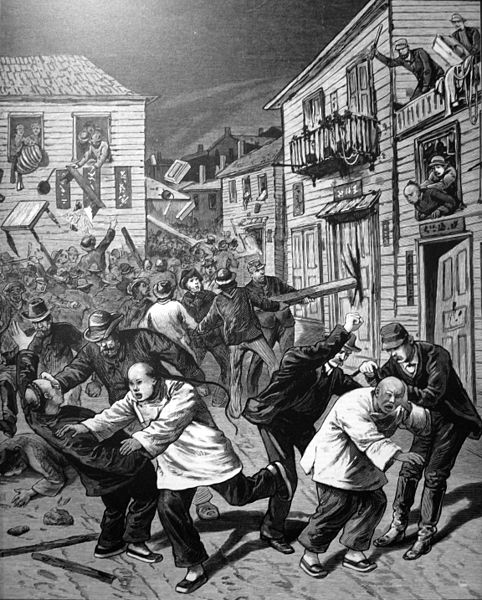

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 47: The US Hybrid War on China, with the Qiao Collective

I talk with a member of the Qiao Collective about the US Hybrid War on China, the sinophobic propaganda that is ramping up, including among declared leftists online, and how to go about trying to develop an understanding about China’s politics and economy in the face of pervasive war propaganda.

Civilizations Series Episode 4: The Enlightened Despots of Europe and Asia

Dave Power and I talk about enlightened despots and the “greats”: Peter, Catherine, Frederick, Akbar, Abbas, Shivaji, Sejeong, as well as the Sikh Empire and the Ayuttaya Kingdom.

The Path of the Unarmed: A novella on Wattpad

Civilizations Series Episode 3: Constitutional Monarchies and England’s Glorious Revolution

With David Power. If the quintessential absolute monarchy was Louis XIV, the quintessential constitutional monarchy is England after the Glorious Revolution. We talk about King Charles losing his head and foreshadow (following Gerald Horne) the dire consequences of this for Africa and Africans as it enabled a massive expansion of the slave trade. For our anarchist listeners, we’ve also got Guy Fawkes, the gunpowder treason, the Diggers, and the Levelers.

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 46: Biden and Imperial Propaganda

Starting with the hectoring of the Bernie movement by liberals to vote Biden – including their sudden discovery of Chomsky, who has always endorsed voting “the lesser evil”. From there, it’s on to early 20th century propaganda in both its British and American imperial incarnations.