The biggest player in the Scramble for Africa was England. Second place to France, third to Germany. But there were many other European powers at the Berlin Conference in 1884 and the plunder of Africa was shared among even the smallest of European countries. Who and how, in this episode of the Scramble for Africa.

Category: Congo and Rwanda Wars

AER 107: Interviewed by the Cadre Journal about the DR Congo and Rwanda

A new youtube channel, the Cadre Journal, has been publishing hour-long in-depth interviews with Communist party activists and others on and largely from the Global South. I was happy to be invited on to talk to them about the history of the US in the DR Congo and Rwanda. Check out their channel – they’re doing an interview a day almost, and they’re all really good.

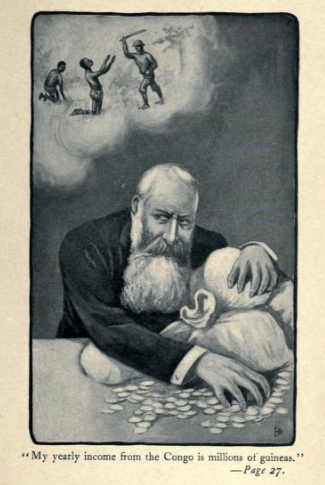

Scramble for Africa 8: Belgium Steals Congo

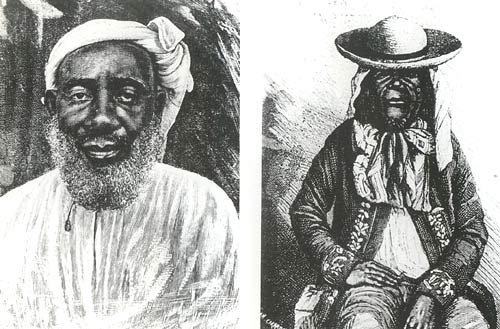

This one is about the precolonial African powers in the Congo – Zanzibar’s representative Tippu Tip, Msiri of Katanga, and a few others (but mainly these two). We talk about their rise in the context of growing European power, and their eventual fall to Belgium – although as you’ll see it wasn’t exactly Belgium, but Leopold II and his British and German allies that made the theft of Congo possible. Another key piece – the centre of the board – falls in the Scramble for Africa.

AEP 64: Rwanda threatens Congolese doctor

A sixteen minute solo episode about James Kabarebe, special presidential advisor in Rwanda, and his recent threatening comments towards Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege.

Read my profile of Mukwege from 2013

Why is Rwanda so afraid of Dr. Mukwege? france-rwanda August 14, 2020

A petition from Bukavu – end impunity in Congo August 2020

The UN Mapping Report on human rights violations in DR Congo 1993-2003

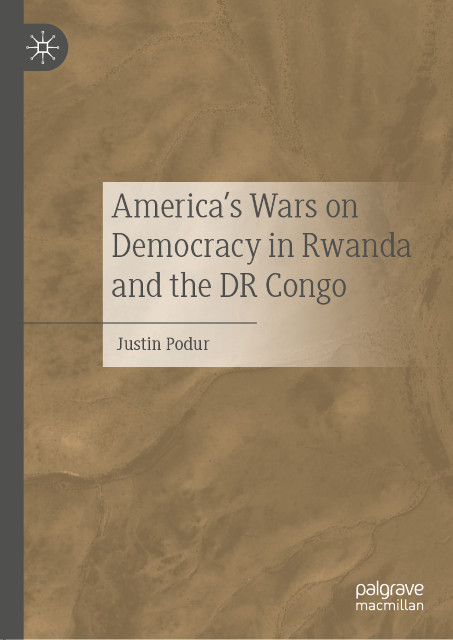

America’s Wars on Democracy in Rwanda and the DR Congo

My new book America’s Wars on Democracy in Rwanda and the DR Congo is published by Palgrave Macmillan in June 2020. Here’s the blurb:

This book examines US interventions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda — two countries whose post-independence histories are inseparable. It analyzes the US campaigns to prevent Patrice Lumumba from turning the DR Congo into a sovereign, democratic, prosperous republic on a continent where America’s ally apartheid South Africa was hegemonic; America’s installation of and support for Mobutu to keep the region under neo-colonial control; and America’s pre-emption of the Africa-wide movement for multiparty democracy in Rwanda and Zaire in the 1990s by supporting Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). In addition, the book discusses the concepts of African development, democracy, genocide, foreign policy, and international politics.

Don’t expect justice from the Imperial Criminal Court

The ICC provides no legal counterbalance to the arrogance of an empire’s power. It is the empire’s court.

In June, a group of international lawyers sued the European Union for crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court (ICC). The lawyers claim that when the EU switched to a policy of deterring refugees trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2014, in particular trying to prevent Libyan refugees from fleeing their destroyed state, they killed thousands of refugees and sent tens of thousands more back to Libya to be enslaved, tortured, raped, and killed.

As a symbolic gesture, the lawsuit is powerful. But the possibility of getting justice for Libyan refugees from the ICC is practically nonexistent.

In fact, the ICC bears some responsibility for the destruction of the Libyan state that led to the refugee crisis in the first place. When the United States decided to overthrow Gaddafi in 2011, it had the UN Security Council make a “referral” of the Libyan situation to the ICC. There were some peculiarities in the details of the referral as well: the ICC was directed to investigate the situation in Libya, exempting non-state actors, since February 15, 2011. “It would appear,” scholar Mark Kersten writes in a chapter in the 2015 book “Contested Justice” (pg. 462), “that the restriction to events after 15 February 2011 was included in order to shield key Western states… In the years preceding the intervention, many of the same Western states that ultimately intervened in Libya and helped overturn the regime had maintained close economic, political and intelligence connections with the Libyan government.” The African Union, led by the South African president, tried to broker a peace deal between Gaddafi and the rebels: Gaddafi accepted, but the rebels refused. For them, Gaddafi had to go. And the ICC investigation strengthened their hand. In Libya, the ICC was harmful to a negotiated solution.

In general, the ICC prefers war to negotiated peace. As scholar Phil Clark pointed out in his 2018 book “Distant Justice” (pg. 91): “… the ICC has expressed immense skepticism toward peace negotiations involving Ugandan and Congolese suspects whom it has charged — especially when those talks involve the offer of amnesty — but has strongly supported militarized responses to these suspects and their respective rebel movements. In short, the ICC has viewed ongoing armed conflict rather than peace talks as more useful for its own purposes.” The president of the DR Congo’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission told Clark in an interview (pg. 223): “The ICC came up forcefully in our discussions with several rebel leaders… We would start talking to them, make good progress, then the conversation would stop. They didn’t want to incriminate themselves, even when we stressed that the amnesty was in place.” In the DR Congo, the ICC made offers of amnesty less credible. Rebel leader Mathieu Ngudjolo was pardoned in 2006, integrated into the army, promoted to the rank of colonel, and then arrested on an ICC warrant 18 months later: the government’s “duplicity toward an amnesty recipient undermined the broader use of amnesty as an incentive for members of rebel groups to disarm” (pg. 203).

The ICC’s careful selection of when it investigates crimes (like limiting its Libya investigation to crimes after February 15, 2011, or its predecessor the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda limiting its investigation to crimes committed after the assassination of the Rwandan president on April 6, 1994) is mirrored in its careful selection of where it investigates and where it ignores. Take the DR Congo again: the ICC limited its mandate to the province of Ituri. Horrific violence took place in Ituri, but there was less violence overall than in the Kivu provinces (especially North Kivu). Why didn’t the ICC investigate in the Kivus? Because in the Kivus, the worst crimes were committed by armed groups supported by Rwanda and Uganda, favored U.S. allies in the region. When Sri Lanka’s government killed tens of thousands of people at the end of its counterinsurgency war against the Tamil Tigers in 2009, the ICC wrung its hands: Sri Lanka wasn’t a signatory to the Rome Statute that empowered the ICC.

The ICC gets even twistier when it comes time to prevent accountability for Israel. After the Goldstone report on Israel’s massacres in Gaza in 2008/9, Palestinians tried to bring a suit to the ICC against the Israeli generals and politicians who organized them. David Bosco reports in his book Rough Justice(pg. 162) that the Israelis met with Ocampo and “pressed Moreno-Ocampo to determine quickly that Palestine was not a state and that the court could therefore not accept its grant of jurisdiction.” The Americans told Ocampo “that they saw little value in ‘criminalizing the world’s longest running and most intractable regional dispute.’” Moreno saw the light: “The prosecutor’s long-awaited decision on Palestine — released in April 2012… more than three years after Palestine asked the court to investigate, the prosecutor decided that it was not his role to determine Palestine’s legal status.” The massacred Palestinians were colonized, and therefore stateless. Only states can sign the Rome Statute and bring the ICC in. Therefore, the ICC had no jurisdiction over the 2008/9 massacres of the Palestinians.

When the U.S. and UK saw no benefit to having the ICC involved in Afghanistan, the ICC prosecutor (Bosco, pg. 163): “limited himself to occasional private requests and put no pressure on involved states. That approach contrasted sharply with his willingness to sharply chastise states for their failure to enforce existing arrest warrants.”

Given the proclivity of the Western coalition in Afghanistan for bombing weddings and operating death squads (sometimes euphemistically called “kill teams”), their squeamishness in the face of potential legal probes is understandable. The ICC, like its predecessor tribunals on Rwanda and Yugoslavia, fully understands that the U.S. and UK are exempt from its brand of justice. Bosco (pg. 66) quotes British Foreign Minister Robin Cook speaking about the international tribunal after the Kosovo war in 1999: “If I may say so, this is not a court set up to bring to book Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom or Presidents of the United States.” Legal scholar Hans Kochler, writing in 2003 (pg. 178), quoted NATO spokesman Jamie Shea, who responded, when asked if he would accept the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia (ICTY)’s jurisdiction over NATO officials: “… I think we have to distinguish between the theoretical and the practical. I believe when Justice [Louise] Arbour starts her investigation, she will because we will allow her to. It’s not [Serbian President Slobodan] Milosevic that has allowed Justice Arbour her visa to go to Kosovo to carry out her investigations. If her court, as we want, is to be allowed access, it will be because of NATO… So NATO is the friend of the Tribunal, NATO are the people who have been detaining indicted war criminals for the Tribunal in Bosnia.”

NATO’s spokesman reminded the world that as a “practical” matter, since it was Western militaries and police services that provide the law enforcement services to the ICC, these Western militaries wouldn’t subject themselves to the ICC’s justice. The second ICTY prosecutor, Carla Del Ponte, admitted her dependence on NATO forces and the partiality of justice that ensued (quoted in Bosco pg. 66): “if I went forward with an investigation of NATO, I would not only fail in this investigative effort, I would render my office incapable of continuing to investigate and prosecute the crimes committed by the local forces during the wars of the 1990s.”

The ICC’s prosecutors depend on Western forces to make arrests and renditions. The ICC also recycles intelligence material from these Western countries into evidence against ICC suspects. This should be a legal problem: intelligence material is not evidence. There are many people trapped in Kafkaesque situations precisely because courts used intelligence materials — which are best guesses and probabilities used to inform police and military actions usually before events occur — as evidence, which should consist of provable facts intended to hold people accountable after the fact. Canadian academic Hassan Diab — imprisoned in France based on a similar-sounding name in a notebook from an intelligence agency interrogation — is just one example.

There was a time, decades ago, when the ICC was forming, when American and Israeli officials were actually worried about the prospect of a court that had universal jurisdiction. Suddenly, U.S. officials talked about national sovereignty. At that time you could hear John Bolton arguing that it was a bad idea “assert the primacy of international institutions over nation-states.” Bolton was very explicit about his problems with the U.S. being a party to the ICC, as quoted by Mahmood Mamdani in 2008:

“‘Our main concern should be for our country’s top civilian and military leaders, those responsible for our defense and foreign policy.’ Bolton went on to ask ‘whether the United States was guilty of war crimes for its aerial bombing campaigns over Germany and Japan in World War II’ and answered in the affirmative: ‘Indeed, if anything, a straightforward reading of the language probably indicates that the court would find the United States guilty. A fortiori, these provisions seem to imply that the United States would have been guilty of a war crime for dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This is intolerable and unacceptable.’ He also aired the concerns of America’s principal ally in the Middle East, Israel: ‘Thus, Israel justifiably feared in Rome that its pre-emptive strike in the Six-Day War almost certainly would have provoked a proceeding against top Israeli officials. Moreover, there is no doubt that Israel will be the target of a complaint concerning conditions and practices by the Israeli military in the West Bank and Gaza.’”

Near the end of his term, Clinton signed the Rome Statute. At the beginning of his term, George W. Bush had Bolton “unsign” it, and negotiate bilateral agreements with the countries of the world that they would never hand Americans over to any international courts. The U.S. went even further, passing in 2002 the Armed Service-Members Protection Act, which includes the line: “The United States is not a party to the Rome Statute and will not be bound by any of its terms. The United States will not recognize the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court over United States nationals.” Then the U.S. got the Security Council to pass resolutions enshrining U.S. immunity.

Israel also never signed the Rome Statute, which is why its officials are now arguing that the ICC has no jurisdiction in an ICC suit about another massacre it committed, this time on a boat trying to relieve the Gaza siege in 2010.

The powerful are exempt from the ICC’s justice. But the U.S. does believe in a kind of universal jurisdiction: its own. Kochler (2003, pg. 106) cites an internal Department of Justice memorandum from the George H.W. Bush era stating the opinion that the FBI has the power “to apprehend and abduct a fugitive residing in a foreign state when those actions would be contrary to customary international law.” That memo was from 1989, and it was about arresting Manuel Noriega, the president of Panama who fell afoul of the U.S., whose country was bombed and invaded, and who was taken away to jail.

The ICC won’t be doing anything for Libyan refugees or the victims of Israel’s massacres, but it continues to make strong statements about Sudan’s now ousted president Omar al-Bashir, who is wanted for crimes committed as part of a counterinsurgency campaign in Darfur. The trial of an African leader from an enemy state, more than a decade after the crimes took place: now this is where the ICC shines.

In 2008, writing about the ICC’s arrest warrant for al-Bashir, Uganda-based scholar Mahmood Mamdani warned that the ICC was becoming a tool of neocolonial domination. The theory implicit in the ICC’s interventions, he wrote, “…turns citizens into wards. The language of humanitarian intervention has cut its ties with the language of citizen rights. To the extent the global humanitarian order claims to stand for rights, these are residual rights of the human and not the full range of rights of the citizen. If the rights of the citizen are pointedly political, the rights of the human pertain to sheer survival… Humanitarianism does not claim to reinforce agency, only to sustain bare life. If anything, its tendency is to promote dependence. Humanitarianism heralds a system of trusteeship.” And what is an empire if not a system of trusteeship?

The ICC provides no legal counterbalance to the arrogance of an empire’s power. It is the empire’s court.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

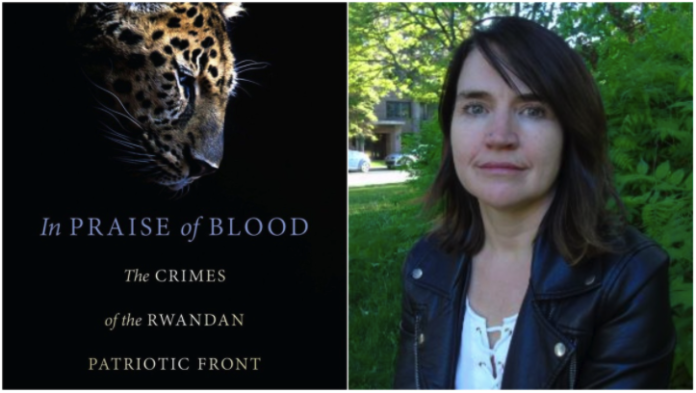

The Ossington Circle Episode 30: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front with Judi Rever

I talk to Judi Rever, author of the important new book In Praise of Blood: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front. We start with the inception of the military force that would become the RPF in 1980s Uganda and follow it through the civil war and genocide to contemporary Rwanda and the Congo. The mind-boggling deaths and atrocities of the many Central African wars and the central role of Paul Kagame are the focus of this interview.

Escalating violence in Burundi

Even when there are constitutionally mandated term limits, many leaders try to hold on to power. In Central Africa (where the small country of Burundi, with its population of 10 million, is located) there are several leaders that have tried, or are trying, to bend the rules to stay in office. The DR Congo, Burundi’s giant neighbour, is currently the site of a democratic movement to try to uphold the Constitution and stop President Joseph Kabila from changing the rules to stay in office. Rwanda is sometimes called Burundi’s ‘twin’: it has about the same land area. It has about the same population (slightly higher), which has the came ethnicities in the same proportions (Tutsi minority, Hutu majority, and Twa). It was once jointly ruled with Burundi by the colonial powers. In Rwanda, too, the president, Paul Kagame, has recently made all the necessary moves to stay in power beyond his term limits – a special exception to the Constitution, just for him.

The current round of political violence in Burundi began in April when its president, Pierre Nkurunziza, announced that he intended to seek a third term in office. In May, a military coup was attempted against him, and failed. In July, Nkurinziza was re-elected with 69% of the vote, after months of heavy-handed tactics. The opposition did not recognize the legitimacy of the result. A major crackdown on the opposition by the government began in November – hundreds killed, hundreds of thousands displaced to neighbouring countries. Now, after the failed coup and the disputed election, Nkurunziza’s government is facing an armed rebellion.

Rebels attacked military bases on December 11th with 87 deaths before the attacks were repulsed. The next morning the capital city, Bujumbura, woke up to find 34 murdered bodies in the streets, probably extrajudicial executions. The UN special advisor on the prevention of genocide, quoted in the journal Foreign Policy, raised a dire warning: “I am not saying that tomorrow there will be a genocide in Burundi, but there is a serious risk that if we do not stop the violence, this may end with a civil war, and following such a civil war, anything is possible”.

Some context: Burundi has lived through civil war before, as well as dictatorship and genocide. Scholar Rene Lemarchand has called Rwanda and Burundi “genocidal twins”. Had Burundi’s post-independence ended up a little bit differently, the whole region may have seen a lot less anguish. Immediately after independence in 1959, a multi-ethnic unity party led by a massively popular young leader, Prince Louis Rwagasore, was set to take power electorally. Rwagasore was assassinated by a European in 1961. Within a few years, a group of Tutsi military officers seized power and proceeded to rule an ethnically exclusive state with an iron fist.

In 1972, in the context of a Hutu rebellion, the establishment organized a genocide against Hutu, killing hundreds of thousands, targeting intellectuals and potential leaders. There were new massacres against Hutus in 1988. In 1993, when a Hutu leader, Melchior Ndadaye, won a democratic election, he was assassinated by the army. More massacres followed, and a civil war began. These events, and the refugees of these massacres, influenced events in Rwanda, including the 1990-1994 civil war and the 1994 genocide that occurred there.

Burundi’s civil war ended through a negotiated settlement in 2006, with a UN force installed (its mandate ended at the end of 2014). Analyst Patrick Hajayandi describes the arrangements agreed upon in the settlement:

“The armed and security forces of Burundi are composed of 50% of Hutu and 50% of Tutsi, in line with the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Accords, and the Global Ceasefire Agreement…

In the current national and local government, as well as in both the Parliament and the Senate, officials are also composed of Hutu and Tutsi, at a rate of 60% and 40% respectively. Unlike in previous pogroms that afflicted Burundi, in 1972 and 1993, the integrated nature of social and political life significantly diminishes the prospect of an unraveling genocidal conflagration.”

Hajayandi advocates a cautious approach based on dialogue, and argues that warnings of imminent genocide and talk of foreign military intervention will inflame a situation that could be kept at a low-intensity and resolved through negotiation. Burundi’s citizens, he writes, are “war-weary”, and have shown “great resistance against efforts by war mongers and ethnic entrepreneurs”.

These “war mongers” may include Rwanda, Burundi’s “twin”. Former UN official Jeff Drumtra told journalist Ann Garrison that, working in the Mahama refugee camp for Burundian refugees in Rwanda, he saw a Rwandan rebel recruitment (perhaps better described as conscription) effort. The rebels would be conscripted and then sent into Burundi. In a letter to the Washington Post, Drumtra cited an al Jazeera story from July about the recruitment of Burundian rebels in refugee camps in Rwanda.

If Drumtra is correct and the “hand of Rwanda” is at work here, it would not be the first time. Successive waves of rebellions in the eastern DR Congo, most recently the M23 rebellion, were conducted by Rwandan proxies. Rwanda’s president Paul Kagame fought in a war in Uganda, came to power in a war in Rwanda, and ran one war after another in the DR Congo. It would be an obvious observation to note that he favours military solutions over other kinds.

If diplomatic efforts are going to succeed in de-escalating Burundi’s conflict, they may have to apply some pressure on Rwanda to stand down as well. This was done successfully with M23 in the DR Congo, and could be done again.

First published at TeleSUR English: http://www.telesurtv.net/english/opinion/Escalating-Violence-in-Burundi-20151212-0018.html

The end of universal jurisdiction

At the beginning of October, Spain’s supreme court dismissed the case known to Rwanda watchers as the Merelles (2008) indictments. Judge Andreu Merelles had charged forty Rwandan military officials of crimes against humanity, war crimes, terrorism, and genocide, and issued warrants for their arrest. The indictment was launched because some Spanish citizens had been killed in the Rwandan civil war. But it expanded to include Rwandan and Congolese victims of the armed forces of Paul Kagame, the winner of the 1990 civil war and the man who may have just become Rwanda’s President-for-life (more on that below).

The indictments had always excluded Kagame because of Kagame’s presidential immunity. Kagame went about protecting himself in two ways, both of which eventually succeeded. First, Kagame may have reasoned, if the president is immune to prosecution, why not stay president forever, making whatever constitutional changes necessary to do so? Second, the indictments themselves were challenged and the doctrine underlying them, ultimately defeated.

The doctrine in question was called ‘universal jurisdiction’. The idea was that a crimes like genocide and crimes against humanity were not crimes that stopped at national borders. As a result, any country could charge and try those accused of such crimes, even if they were from another country. Universal jurisdiction is a liberal doctrine, analogous to the selectively applied Responsibility to Protect (R2P). Universal jursidiction is not as prone to abuse as R2P mainly because it is not as asymmetric as R2P: any country with a judiciary can hold a trial and issue arrest warrants, but only two or three countries in the world have the military might to send military forces to other countries, whether on the pretense of protecting people or some other. For non-superpowers, for smaller countries, there was only the threat of the law.

Spain was just such a small country whose judges took up the law against human rights abusers in other countries. Under the universal jurisdiction doctrine it attempted to try Chile’s dictator Augusto Pinochet, Guatemalan military officers, and Argentinian military officers. But the Spanish judges didn’t just chase fallen dictators from smaller countries. They also pursued former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, US soldiers for crimes in Iraq, Chinese politicians for crimes in Tibet, and Israeli generals for massacres of Palestinians.

By going after the big fish and people currently in power, the Spanish judges set alarm bells ringing. Israel, which famously used the doctrine of universal jursidiction in its trial of Eichmann 1961, got the investigation against its officers stopped. Kissinger argued that the doctrine would degenerate into show trials against political opponents.

Last year, Spain’s legislature reduced the applicability of universal jurisdiction. An NYT article (Feb 10/14, “Spain Seeks to Curb Law Allowing Judges to Pursue Cases Globally”) suggests that China was the last straw. But the doctrine was targeted earlier. And the last straw was not China, but the arrest in June of one of Rwandan ruler Kagame’s intelligence officers, Karenzi Karake, in London, on a European arrest warrant filed based on Merelles’s 2008 indictments. Karake was released in August through the strenuous efforts of the Blair family (Tony Blair is a friend and advisor to Kagame, and Cherie Blair was Karake’s lawyer). Less than two months later, Merelles’s indictments were dismissed in the Spanish Supreme Court.

Kagame and his men could breathe a little easier. As for Kagame himself, lest any other countries get any universal jurisdiction ideas, the Rwandan parliament voted to allow Kagame to extend his tenure beyond the end of his term limits in 2017. Maybe he’ll stay on until 2034. The parliament didn’t change the law for everyone: just for Kagame.

Is anything left of the indictments? For 29 of the 40 indicted, there remains a possibility of prosecution should they enter Spanish territory.

But the doctrine on which it is based, universal jurisdiction, has been eroded. Journalist Judi Rever, describing the case in the Digital Journal, used the term “gutted”. After this decision, the international legal arena has become a bit safer for war criminals.

Partial justice and victor’s justice will still take place through these international tribunals. If you are a dictator, if you lose a war, if you end up on the wrong side of Western weapons – you should continue to fear trial and execution in international courts.

But if you are perpetrating crimes against Asians or Africans, in places like Rwanda or the DRC, or in Palestine or Afghanistan or Iraq, under the protection of a major power like the US – well then, rest easy. The law will not get you.

First published TeleSUR English: http://www.telesurtv.net/english/opinion/The-End-of-Universal-Jurisdiction-20151113-0010.html

The Beginning of the End for Kagame?

On June 22, 2015 it was reported that the director-general of Rwanda’s National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS), Emmanuel Karenzi Karake, was arrested in London. One report, by Judi Rever in the Digital Journal, refers to Karenzi Karake accurately as “Kagame’s spy chief”. Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda, rose to power as an intelligence chief himself – working for Yoweri Museveni, the ruler of Uganda, during the 1980s Bush War in that country. Kagame would not choose a spy chief lightly, and Karenzi Karake is absolutely in Kagame’s inner circle.

Interpol is responsible for the arrest, and was acting on indictments issued by a Spanish Judge, Fernando Andreu Merelles, in 2008. Merelles issued indictments for forty of Kagame’s men, all of whom were in command positions of Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) at the end of the Rwandan Civil War and genocide of 1994. Having defeated and replaced the Rwandan government that committed the genocide, Kagame’s RPF hunted and massacred Rwandan refugees during and after the Rwandan civil war, in the areas they controlled (and in the DR Congo).

The evidence of these massacres is irrefutable. In standard accounts of the genocide, including the basic Human Rights Watch book Leave No One to Tell the Story by Alison Des Forges, massacres by the RPF are presented, though no estimates are given on their scale. A famously buried report by UN investigator Robert Gersony, which has since surfaced, estimated the scale to be in the tens of thousands – during the civil war. Some of the largest, and best documented massacres by the RPF occurred after they had already won the war – the worst and most infamous being the Kibeho massacre of April 1995.

Scholar Gerard Prunier, who wrote one of the standard accounts of the Rwandan genocide and one of the major books on the Congo wars, Africa’s World War (Oxford University Press 2009), was a long-time friend of the RPF since before the Civil War. In his book, he expresses considerable understanding and empathy for the RPF, arguing that RPF violence “had to be seen in the context of the war and of the genocide”, that there were going to be some “unavoidable revenge killings”. But when one of the few Hutu members of the RPF, Seth Sendashonga, also a friend of Prunier’s, tried and failed to stop the Kibeho massacre, after sending 400 memos over 13 months to Kagame to try to stop these killings (memos to which Kagame studiously avoided replying in writing), Prunier was forced to start changing his mind. Sendashonga went into exile and was assassinated in Kenya in 1998 – Prunier reports this murder as causing his final break with the RPF. Prunier called the RPF’s campaign of killings “coherent”, with their “focal point” being “undivided political control”. Targets included “friends and family of genocidaire, educated people, PARMEHUTU (from the Hutu political party), and opponents” – a broad and ever-expanding pool of potential victims. The RPF, Prunier wrote, viewed the Hutu majority population, whether they were involved in politics or not, whether they had anything to do with the the genocide or not, as a “permanent danger” to be kept at bay with “random mass killings to instill fear and defanged by neutralizing real or potential leaders”.

Merelles’s indictments are based on testimony by ex-RPF soldiers, like the 2014 BBC documentary that stirred so much controversy. The 182-page legal document outlines specific charges against specific commanders for specific massacres in different parts of Rwanda. Like the BBC documentary, it has generated enraged responses from Kagame’s supporters, both in Rwanda and in the West. The standard enraged response is to counter-accuse, and attack the source as being “pro-genocide”. The idea is that Interpol and a Spanish judge are, in 2015, working on behalf of the Hutu forces that committed the genocide and were militarily defeated, scattered, hunted, and slaughtered by the RPF (along with hundreds of thousands of perfectly innocent civilians) two decades ago, during which some of their leaders were also convicted in the International Criminal Court.

The explanation might be somewhat simpler – that, according to this judge, the fact that Kagame and the RPF fought against a government that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians did not grant them the right to kill hundreds of thousands of civilians.

Merelles’s 2008 indictments are not the only documents sitting out there in the public domain that contain enough evidence to condemn Kagame and the commanders around him to jail. There are also a number of United Nations reports, including the UN Mapping Report on the Congo and a series of reports on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources in the Democratic Republic of Congo. There are also indictments from another judge, Jean-Louis Brugiere of France, from 2006. Most who know about Kagame’s crimes assumed that these documents would mainly collect dust.

But slowly over the past five or so years, and especially since the BBC documentary was aired last year, even as Kagame seeks to change the constitution to remove term limits and stay in office beyond 2017, it does look like something has changed in the West’s treatment of him. The automatic smear that anyone seeking accountability for the RPF’s crimes must be a ‘genocidaire’ is not sticking as well it used to. The evidence that Kagame and the RPF are responsible for assassinations and massacres in Rwanda and Congo, as well as plunder and occupation in the Congo, is overwhelming and hard to ignore, as hard as Kagame’s supporters try. The idea that the 1994 genocide gives Kagame and the RPF impunity to commit crimes against humanity holds so little weight that no one is willing to say it out loud. Now his spy chief has been arrested in one of the countries, the UK, that has supported Kagame the most unconditionally. If the UK is not safe for a war criminal, then where in the West is?

If Kagame can’t shake off the stench of crimes against humanity, he may find himself becoming another one of the West’s dispensable dictators. Joseph Kabila has, after all, demonstrated that he can fulfill Western interests in the DR Congo directly, without the need for Rwanda’s middle-management – especially if the UN continues to provide soldiers to do it.

Kagame and his once-patron, Museveni of Uganda, were once touted by the US as the ‘New African Leaders’. But perhaps they are approaching their shelf life. If so, they may suddenly be ushered off stage and replaced some time soon. If the West remains the arbiter of what happens there, the people of the region can have little to hope for from their replacements.

First published at TeleSUR English: http://www.telesurtv.net/english/opinion/The-Beginning-of-the-End-for-Kagame-20150626-0023.html