The focus on Hamas is a product of the rolling amnesia of empire, as if the history of Israeli attacks on Palestinians can be narrowed to the last few decades, then distorted further. Against this tendency, this episode reviews the basic historical and geographic background to this crisis, showing the place of Palestine and the Gaza Strip in the history of imperial expansion, and placing the current horrors in their essential context.

Category: Antiwar writings

Episode 46 of In the Context of Empire

I was a guest on the fantastic podcast, In the Context of Empire, where I spoke with co-host Matt McKenna about lots of things, but mainly about how imperialist propaganda works.

AEP 80: My comments on The Arrest of Meng Wanzhou and the New Cold War on China

On March 1, I was on a panel hosted by the Hamilton Coalition to Stop the War, the Canadian Peace Congress, World Beyond War, the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute, and Just Peace Associates. The topic was “the Arrest of Meng Wanzhou and the New Cold War on China”. Other panelists were Radhika Desai, William Ging Wee Dere, and John Ross – all of whom covered different aspects of the situation. I focused my remarks on Canada’s own record of genocide and racism, summarizing some of what we’ve been talking about in recent Civilizations episodes. The whole panel is out there on youtube – this audio is just my talk, 17 minutes long.

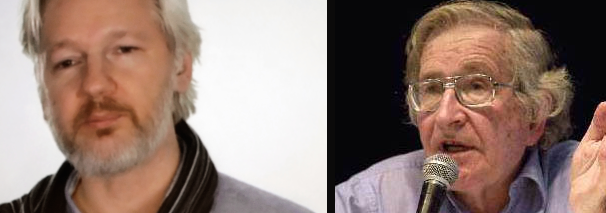

AEP 70: Reading Chomsky’s statement to the Assange Trial

On the last day of defense evidence in the Assange Trial (September 30/20), a statement from Chomsky was read into the record. This is a solo episode where I go over Chomsky’s succinct, remarkable statement about power, propaganda, and the importance of Assange’s work.

AEP 64: Rwanda threatens Congolese doctor

A sixteen minute solo episode about James Kabarebe, special presidential advisor in Rwanda, and his recent threatening comments towards Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege.

Read my profile of Mukwege from 2013

Why is Rwanda so afraid of Dr. Mukwege? france-rwanda August 14, 2020

A petition from Bukavu – end impunity in Congo August 2020

The UN Mapping Report on human rights violations in DR Congo 1993-2003

AEP 59: The American Trap sprung on Tiktok and Huawei, with Carl Zha

Back with Carl Zha of Silk & Steel podcast, who we last saw in our episode on the India-China border conflict.

We’re thinking of calling this the Kung Fu Yoga series. In this one, Justin has just finished reading the terrifying book The American Trap by Frederic Pierucci (which Carl notes has 100,000 reviews for the Chinese edition so far). Pierucci was jailed for 30 months in the US in a 5-year long ordeal that ended in his company, the French multinational Alstom, selling off its entire nuclear division to General Electric.

We talk about Pierucci’s case in detail and its relevance to the kidnapping of Meng Wanzhou of Huawei and Trump’s ban of Tiktok: the use of the US’s judicial apparatus to seize billions in assets from other countries, including allied countries, and including entire businesses.

Carl thinks China’s only possible response is to build its own tech stack from the bottom up.

Chomsky vs the Media, 2020 version

Chomsky signed a letter about free speech and something called “cancel culture“, which has prompted a small social media wave of responses.

There is a good piece by Jonathan Cook about how focusing on Chomsky’s signature misses the point. But I am going to focus only on Chomsky here.

My argument: Chomsky’s most powerful message is anti-imperialism. Containing that message has been the preoccupation of the propaganda system since the 1960s.

In 1973, they shut down a whole company and pulped the print run of his book with Ed Herman, Counter-Revolutionary Violence.

Mostly, though after the peak of protests, he was just driven out of the mainstream. He published with activist publishers and the alternative media.

Like Z Magazine and ZNet, one of the principals of whom was Michael Albert, who’s now… a podcaster.

Beyond marginalizing him, they also smeared him. Because he compared Indonesia’s Timor massacres to Cambodia massacres, they called him denialist.

A French publisher slapped a free speech essay he wrote on a holocaust denier’s book, and they smeared him about that.

In the 1990s, a new generation of people discovered Chomsky on the web. The web was different then. Not fully sealed up by the tech giants.

Chomsky’s influence grew and some of the alternative media also grew and became mainstream or close. By the time of the Afghanistan War 2001, he could no longer be marginalized.

Indeed it became a good careerist move to make a showy denunciation of Chomsky in the mainstream. It worked for Samantha Power, for example.

A hilarious 2005 interview by Emma Brockes in the Guardian resulted in a very extensive corrections page that was basically a retraction.

Johann Hari, who went somewhat downhill and then turned around and did some good work since, invented a comment by Chomsky at a luncheon.

George Monbiot did the same in the 2010s, and others.

These are just off the top of my head and intended to reveal the particular way that Chomsky was handled by the mainstream in the 2000s: try to introduce inaccuracies and falsehoods; prove your liberal credentials by denouncing Chomsky the leftist.

Chomsky’s influence didn’t stop, but the whole media ecosystem that he analyzed has changed. So has the strategy for containing him.

The strategy today is to select the views that he holds that are closest to the mainstream and amplify those, while de-emphasizing the anti-imperialism.

That’s what the Intercept does when it sends someone to interview Chomsky on how Biden is the lesser evil.

That’s what the new “cancel culture” petition is about.

Yes, Chomsky is a free speech absolutist, he’s a lesser-evilist on electoral politics, he’s a two-stater on Palestine, he broadly prefers nonviolent strategies, and is critical of every state, including those targeted by imperialism.

But can find those views everywhere in the mainstream. They are not why people admire Chomsky and they are not why imperialists hate Chomsky.

Chomsky says that every US president is a war criminal.

Chomsky talks about the US sanctions against Cuba.

Chomsky talks about the US-led counterinsurgency in Colombia.

Activists in every anti-war movement in the US since the Vietnam war have relied on Chomsky’s analysis and arguments; including movements against Israel’s wars in Lebanon & Occupied Palestine.

Chomsky talks about how propaganda systems work and push for war.

Chomsky believes in challenging the reader or audience: in Canada, he talks about Canada’s crimes, because it’s cowardly to denounce crimes you can’t affect while doing nothing about crimes you can affect.

There’s much more. My point: Chomsky is a proven person of principle, impossible to deny. The Biden people, the “cancel culture” people, they want to use that to advance their agendas.

As they do so, they want you to forget the anti-imperialism that is what Chomsky is really about and has been about for 50 years.

This is just the 2020 iteration of the campaign to contain Chomsky’s anti-imperialism.

Whether you’re disappointed that Chomsky signed that letter or newly concerned about cancel culture because Chomsky signed the letter, consider this option – read enough of his work to get a sense of what it is about, and if you like his ideas, principles, and methods try to assimilate them into your world view.

GUEST POST: 21st Century Fascism? I’m afraid so.

by Hector Mondragon, November 12 2018. Translated from Spanish by Justin Podur.

Facing the wave of growth and success of political and social movements of the ultra-right, it is necessary to ask: are we witnessing the rise of a series of fascist movements in many parts of the world as occurred in the 1930s? Or is fascism an unrepeatable historical phenomenon limited to the period between the two world wars?

Some consider that fascism only arose to prevent the victory of socialist revolutions or to stop the communists, but “fascism did not triumph when the bourgeois was threatened with proletarian revolution, but rather when the working class was weakened and put on the defensive.” The role of fascism was not to overcome the socialist revolution but to “erase the conquests of reformist socialism.”i

In Germany it was the social democrats that liquidated Rosa Luxemberg and Karl Liebnecht and stopped the communists fifteen years before the Nazi triumph. The Soviet Republic in Hungary was stopped by the invasion of the Rumanian army sent by the Liberal party. In Italy the occupations of the factories and the workers’ councils were stopped by the Liberal Party two years before the triumph of the fascists. Fascist propaganda insisted and insists always on a “communist threat” but for the past 90 years, capitalism has used the fascist “solution” to destroy reforms and human rights after the “communist threat” has been defeated.

What then is the difference between the Italian blackshirts, the German brownshirts, the Rumanian iron guards, the Ukrainian flagmen, the Hungarian arrow cross, the Spanish falange or the Croation Ustache – and today’s ultra-right parties?

All of the protagonists of European fascism of the last century professed a visceral hatred of Jews, expressed in extreme form in Germany, Ukraine, Romania and Croatia and culminating in the Holocaust. Today, by contrast, with the exception of Ukraine’s Svoboda, Hungary’s Jobbik, Greece’s Golden Dawn, the KKK and a few small neonazi groups, the majority of the global right is pro-Israel and supports the extermination of the Palestinians.

In general, on the xenophobic right, anti-Semitism has been replaced by Islamophobiaii, hatred of refugees, and particular racisms, like that expressed on the US right against Mexicansiii. In other aspects, however, despite its diversity, the 21st century ultra-right bears a growing resemblance to the European fascism of the 1930

. This is not coincidence. Fascism is a phenomenon specific to the crises of certain phases of the imperialist and capitalist order.iv v vi

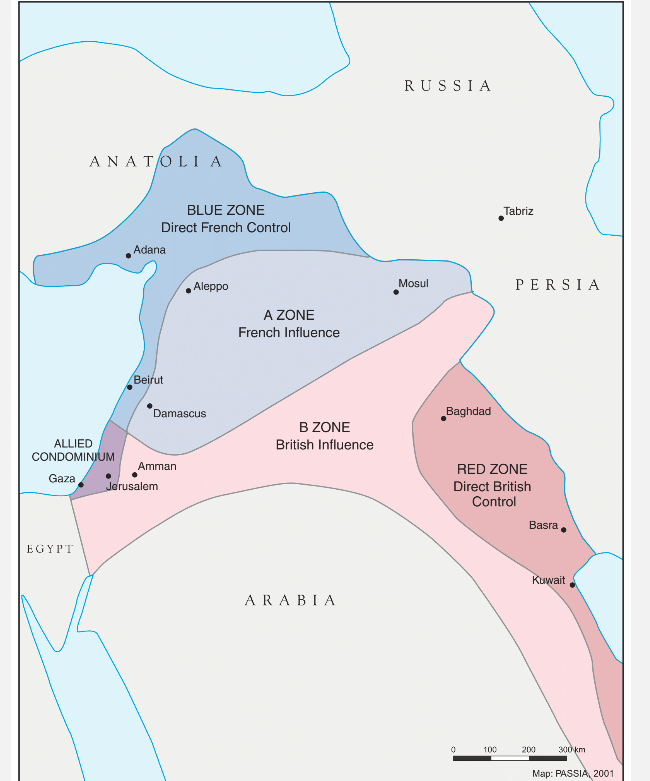

Those who believe in the “end of history” – that colonialism is a thing of the past and capitalism is the final historical order – incorrectly discard the notion of a rebirth of fascism. The reality is very different. In this century so far, imperialist wars have destroyed Iraq, Libya, and Syria, all as a way of resolving the cyclical crises of capitalism. The recolonization of the Middle East is a fact. Colonialism was in retreat during the period that began with the fall of Nazism and ended with the US loss in Vietnam. It has returned with force in the past three decades.

To understand how fascism arises from the necessities of internal and external imperial wars, Hitler’s January 27 1932 speech to the industrialists at Dusseldorf is instructive. This speech convinced big business to support the Nazi solution.vii

Hitler explained that the defense of private property required a dictatorship like that of the Fuhrer. Because private property is the result of economic inequality and different classes of citizens, to defend private property it would be necessary to impose political inequality, hierarchy, and authoritarianism. Hitler explained that England did not just go to India sell its wares; it obliged India to buy them by invading the country. If the businessmen wanted the success of their enterprises, they had to support Nazism to conquer new markets and resources in the wider world and destroy the “Bolshevism” that was damaging the racial and national unity needed for victory.

In this speech, unusually light on Hitler’s characteristic constant attacks against the Jews, Hitler focused on “Bolshevism”: not just the need to stop it, but also to stop it from dividing the people and spreading a mentality opposed to the singular national interest. The businessmen applauded loudly for several minutes. Hitler’s program for big German business included a wave of privatizationsviii ix – and was only stopped by the fall of Nazism itself.

For Milton Friedman and the Chicago School to impose neoliberalism on Chile, it was not just necessary to prepare an elite of Chilean economists. It was also necessary to install Pinochet’s “Patria y Libertad” to impose the laws of the market.

Vilfredo Pareto, the economist considered by neoliberals as the precursor of their “libertarian” ideas, raged against strikes as the enemies of an economic optimum. He hated the worker’s movement’s taking over factories. He celebrated the ascent of Mussolini to power. Even though Pareto himself was not a fascist, the fascists made him a senator-for-life. In the first few years of his government, Mussolini followed Pareto’s prescriptions to the letter, destroying political liberalism, reducing state administration in favor of private enterprise, reducing property taxes, favoring industry, and imposing religious education.x The capitalists and neoliberal economists would prefer not to associate with fascists and repudiate their ideology, but they acclaim it when it is time to smash “Bolshevism” and go to war with other countries.

As it did 90 years ago, fascism today liquidates the gains of workers and collective rights, cleanses universities and schools, and promotes war. When the domination of transnational capital is not maintained merely by the laws of the market, it is maintained by direct violence. When institutional solutions are insufficient, the mass mobilization of one part of civil society is used against the rest.

Colonialism has strengthened. What is today called “extractivism” was once called “accumulation by dispossession”. It reigns throughout multiple parts of the world, an expression of the strength of colonial enterprises that have existed for centuries. It is the exact same primitive accumulation that occurred in the original phase of colonialism.xi xii

In the 20th century, war was integrated with colonial enterprise and the destruction of competitor capital (as we saw in Iraq, Libya, and earlier in Yugoslavia) in a way that foreshadowed the destruction of local capital, the conquest of new markets, new investment zones and sources of land, minerals, gas and petroleum.

But imperialism, colonialism and war are not in themselves fascism, which is a mass movement based in the middle class and the unemployed, mobilized in diverse forms – including armed militias – to destroy workers’ rights and organizations and perpetuate war in the interests of transnational capital and landowners. In Latin America, the landowners always have their paramilitary bands at the readyxiii.

In contrast to other forms of authoritarianism, the success of fascism is guaranteed by the mass mobilization of the middle class against the “enemies of the nation”, be they Jews, Communists, Africans, refugees, Muslims, or Mexicans.

As the Nazi philosopher Martin Heidegger said, “ …it can accordingly seem that there is no enemy. It is then a fundamental requirement that the enemy be found, brought to light, or even created so that this stand against the enemy may take place… with the goal of complete extermination.”xiv

The state that persecutes the enemy, according to the theorists of nazism, is not merely the judicial institution, but the people’s Being intrinsically united with its leader (Heidegger). It’s not a state machinery, but the people organized by the nazi party organized through its Fuhrer that is the source of law (Rosemberg). It is not the law that establishes order, but the “movement” that imposes an order, from which the law springs(Schmitt).xv

This is why Gramsci, in his Prison Notebooks, presented the thesis that civil society is itself a form of the state. This makes the problem of emancipation more complicated and more dramatic. “Civil society could very well express violence and oppression not inferior to that of the state, and very unscrupulous besides, and it will tend to exercise this violence without obstructions since it has no concern with even the pretense of impartiality.”xvi

The idea of needing to attack an enemy was and is a part of an ultra-right wing strategy, with false information used to agitate about the fantasy of the enemy. The great theorist of what is now called “fake news” was the publicist of Siemens and the Reemtsma tobacco company, Hans Domizlaff, who began his application of marketing techniques to politics in 1932.xvii

According to Domizlaff, “people can believe in gross lies or, in any case, there can be found freedom for action if lies are openly told and obstinately maintained…xviii the masses cannot be educated, only domesticated, led, and voided.”xix

In the 21st century the role of enemy is assigned in Europe and the US to migrants, especially refugees or to “terrorist” Muslims. In Latin America it continues to be “communists”, the political left, as it was in the time of the Doctrine of National Security.

But more and more, in the north and in Latin America, LGBTQ communities are targeted, called the “gender ideology”, with propaganda about apparent “scientific” research into gender. This is not new.

Homophobia was one of the hooks the Nazis used to win over religious sectors. Magnus Hirschfield’s theory of the “third sex” and his books on homosexuality and transgender were attacked. Hirschfield’s Institute for Sexual Research was the target of homphobic attack. Its administrator Kurt Hiller was sent to a concentration camp in March 1933 and on May 6 the building was occupied and its archives, photos, and library were confiscated to be burned in the famous book-burning of May 10, 1933.xx

The bonfire linked the “judeo-bolshevik conspiracy” and the third sex. Homophobia played a mobilizing role in the bonfire and in the concentration camps. The annihilation of the third sex occurred alongside the extermination of communists, unionists, Jews and Roma – the extermination of the enemy. The state apparatus, from its perch in the universities to its gas chambers, was rooted in the “people’s Being” directed by its leader.

The ultra-right of the 21st century, especially in Latin America, has rediscovered the role of homophobia. The struggle against “gender ideology” was embedded in the “No” vote against the Colombian peace accords and has moved millions of votes from Brazil to the US, including Costa Rica, where an important group of churches joined these homophobic manipulations with enthusiasm.

The manipulation of religion by the ultra-right is not limited to homophobia. For more than one hundred years the right has developed a theology of war. The spread of Wahhabism in the Muslim world has served as the basis for Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, and the “dispensationalism” of Cyrus Scofield has played a role in the West in creating a war theology, nourishing militarism on the evangelical right-wing.

The Islamic State is apocalyptic: it is preparing for the final battle of history, in which Jesus and the Mahdi will fight alongside them. “Dispensationalism” also views war in the Middle East as anticipation of Armageddon and considers US support for Israel part of a divine plan. The faithful expect to be transported directly to heaven before seven years of great disasters, at the end of which will occur the great battle of Armageddon, when Jesus will return to defend Israel.xxi

As the Nazis struggled against the conspiracy outlined in the “protocols of the elders of Zion”, the Latin American ultra-right struggles against the conspiracy of the Forum of Sao Paolo, which they believe wishes to impose communism and homosexualism. Bolshevism, however, has changed: it is no longer a Jewish conspiracy but the source of conspiracy, since Israel is now an ally and the Palestinians the enemy.

The ultra-right of the Americas is diverse, but its common symbols and leaders are always anti-communist, loyal to the US, and loyal to the transnational corporations. Under these three principles, religious fundamentalism can easily co-exist with the debauched life of Donald Trump. The white supremacists of the US are not in agreement among themselves about anti-Semitism. But the Klan and the neo-Nazis continue to co-exist and to coordinate on common projects like the wall on the border with Mexico.

The ultra-right in Europe is more divided. There are anti-EU and pro-EU ultra-rightists. There is one anti-Semitic right and another Islamophobic right. In Israel, the extermination of Palestinians signals fascism; in Islamic countries it’s Wahhabism; in India it is Hindu supermacy and there is even a Buddhist right-wing in Thailand and Burma. All of the ultra-rights deny our common humanity, are xenophobic and racist, homophobic and enemies of human rights and of international law.

Not every ultra-right is fascist. Several have given rise to diverse Bonapartes,xxii xxiii whether by electoral movements or by military-parliamentary-or judicial coups. Laws and repressive means strengthen state oppression, but fascism is not simply the repression of the system towards its enemies. The triumph of fascism is a qualitative change. xxiv xxv

For fascist regimes to establish themselves it is not sufficient for there to be a fascist party, nor is it sufficient that the president be a fascist. Fascism requires a mass movement that is capable of smashing the organizations of workers and of minorities, and capable of supporting perpetual wars. Fascism in the 21st century is reaching that point.

It is time to resist.

i BAUER, Otto (1936) Zwischen zwei Weltkriegen?. Bratislava: Eugen Prager Verlag, p. 136.

ii HUNTINGTON, Samuel 1997 O Choque das Civilizações e a recomposição da ordem mundial. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Objetiva.

iii HUNTINGTON, Samuel 2004. ¿Quiénes somos?: los desafíos a la identidad nacional estadounidense. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

iv MANDEL, Ernest (1969) El Fascismo. Revolta Global, p.10.

v POULANTZAS, Nicos (1970) Fascismo e Ditadura. Porto: Portucalense, 1972, p. 13.

vi DIMITROV, Jorge (1935) “La ofensiva del fascismo y las tareas de la Internacional Comunista en la lucha por la unidad dela clase obrera contra el fascismo”; Informe ante en VII Congreso Mundial de la Internacional Comunista, 2 de agosto de 1935. Selección de trabajos. Buenos Aires: Estudio, 1972.

vii HITLER, Adolf (1932) “The Dusseldorf Speech of 1932”; C N Trueman editor. The History Learning Site, 22 May 2015.

viii BUCHHEIM, Christoph and Jonas SCHERNER (2006).”The Role of Private Property in the Nazi Economy: The Case of Industry”. The Journal of Economic History 66(2) 390-416 (406). Cambridge University Press.

ix BEL, Germà (13 de noviembre de 2004). “Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany”. Universitat de Barcelona i ppre-IREA.

x BORKENAU, Franz (1936) Pareto. New York: John Wiley & Sons, p.40.

xi HARVEY, David (2004) “El ‘nuevo imperialismo’: acumulación por desposesión”; Leo Pantich & Colin Leys (Ed.) El nuevo desafío imperial, p.p. 99-129. Merlin Press-Clacso.

xii MARX, Karl (1867) El Capital, v. I, c. XXIV-XXV. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 1974, p.p. 607-650.

xiii See the character Attila in the film Novecento, by Bernardo BERTOLUCCI (1976).

xiv HEIDEGGER, Martin. Gesamtausgabe, 36/37, Sein und Wahrheit. 1. Die Grundfrage der Philosophie. 2. Vom Wesen der Wahrheit, Frankfurt am Main, Klostermann, 2001, éd. por Hartmut Tietjen, [GA 36/37], 90-91.

xv FAYE, Emmanuel (2005) “El derecho y la raza: Erik Wolf entre Heidegger, Schmitt y Rosenberg”. Heidegger: La introducción del nazismo en filosofía. Madrid: Akal, 2009, 2018, capítulo7.

xvi LOSURDO, Doménico 1997. “Com Gramsci, para além de Marx e Gramsci”; Crítica Marxista 3-4. Roma.

xvii DOMIZLAFF, Hans (1932) Propagandamittel der Staatsidee. Altona-Othmarschen.

xviii DOMIZLAFF, Hans (1952) Brevier für Könige. Massenpsychologisches Praktikum. Hamburg, Institut für Markentechnik, p. 208.

xix Ibidem, p. 288.

xx BAUER, Heike (2017). The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture. Temple University Press, p. 92.

xxi SIZER, Stephen (2006) Sionismo cristiano ¿hoja de ruta a Armagedón? Bósforo libros, 2009.

xxii THALHEIMER, August (1928) “Über den Faschismus”; internes Dokument der Komintern, 1928 ; Gegen den Strom, theoretischer Zeitschrift der KPD(O), 1930.

xxiii TROTSKY, Leon (1934) “Bonapartism and Fascism”; New International, 1(2): 37-38.

xxiv Ibid.

xxv DIMITROV, Jorge; op. cit.

translated by Justin Podur

The Brief Episode 10: Canada’s Saudi Arms Deal

Saudi Arabia’s $14 billion weapons deal puts Canadian armoured vehicles on the frontlines of the war in Yemen. We are joined by ANTHONY FENTON to discuss the machinations of Canada’s junior-partner imperialism.

Episode: 010 Canada’s Saudi arms deal

Date: 16 May 2020 | Length: 66:00

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 47: The US Hybrid War on China, with the Qiao Collective

I talk with a member of the Qiao Collective about the US Hybrid War on China, the sinophobic propaganda that is ramping up, including among declared leftists online, and how to go about trying to develop an understanding about China’s politics and economy in the face of pervasive war propaganda.