I had the privilege of being on the wonderful Oats for Breakfast podcast by the Socialist Project. The co-hosts, Umair Muhammad and Karmah Dudin, did an amazing reading of the book and I had a great time talking to them.

Hosted by Justin Podur

I had the privilege of being on the wonderful Oats for Breakfast podcast by the Socialist Project. The co-hosts, Umair Muhammad and Karmah Dudin, did an amazing reading of the book and I had a great time talking to them.

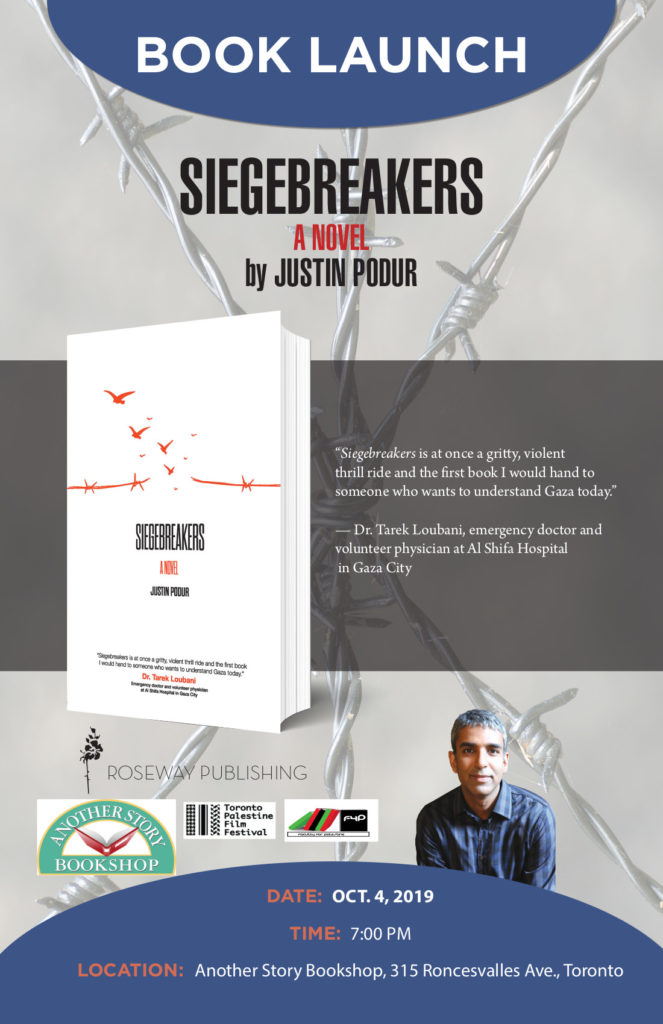

A discussion between Siegebreakers author Justin Podur and journalist Jon Elmer. Recorded on Oct 4/19 at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto.

On October 4, 2019, I read Chapter 5 of my latest novel, Siegebreakers, at the book launch at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto.

In Siegebreakers, all of the main characters face a serious, and very concrete, problem: getting in and out of Gaza.

Some are trying to get out, and to do that, they have to go through Israel – through Erez Crossing, which is a scene out of a dystopian future. A few years ago I interviewed a doctor who had made the crossing. He talked a bit about what it was like coming and going from Israel, but I also put a description together (for the book) from that and a few other interviews of what it is like to go through Erez (I went through Erez myself in 2002, but that was before it was rebuilt into its current form):

Laila made the long walk through the wire-encaged sidewalk, like an enclosure at a zoo, to the first turnstile. Israel modified these turnstiles to reduce the space between the arms, to press harder against Palestinian bodies. Remote-controlled, of course, by the occupier’s security who watched her progress through the tunnel from above. Through the turnstile — if the invisible occupier chose to open it, by remote control — then, a big steel door. Also, remote-controlled. Once it opened, there was another long, outdoor passageway to the terminal. She rolled her bag along behind her, her shoulders slouching when she forgot herself, but when she remembered, with her back arched and her chin up. She faced the sliding steel doors at the entrance to the terminal, waited in suspense for the occupier’s decision to open or close it. They opened it for her, so she could go through the metal detector and the next set of turnstiles. She put her luggage on the carousel and it disappeared into another room, where someone working for the occupier went through her every possession. Then, the occupier used a scanner to create a three-dimensional model of every centimetre of her body… More remote-controlled doors. More modified metal turnstiles. Laila claimed her bag and went to face the occupier’s passport inspectors, who sat in blast-proof booths. She handed the inspector her documents...

I won’t spoil what happens next, but let’s continue on the problem of getting in and out of Gaza. Anyone trying to get goods in or out of Gaza has to use a different high-tech remote-controlled crossing, Kerem Abu Salem. The description of how that crossing works is assembled from the organization Gisha.org. Play a round of Safe Passage, if you’re up for the frustration.

And then there’s Rafah, the crossing to and from Egypt. Taking a look at Rafah is where you see how much a participant Egypt’s dictatorship is in the siege of Gaza.

Sea and air? Not happening. I wouldn’t even have my fictional characters try. Some years ago I was asked why people don’t just fly into Gaza through Yasser Arafat International Airport. Grand opening: November 1998. Grand closing (via Israeli bombs): October 2000.

The Great March of Return, which has shaped Gaza’s politics for over a year now and which is one event I didn’t anticipate in Siegebreakers, is about all of the rights that are denied to Palestinians, but it is deeply about the fundamental right to come and go, the right to not be born and live one’s whole life in a prison, which is Israel’s (and Egypt’s, and the US, and Canada, and all of the allies collaborating in the siege) design for every single person in Gaza (children included). Abby Martin’s new film, Gaza Fights for Freedom, filmed in large part by Palestinian journalists from Gaza, can show you what it looks like.

Those people marching to the fence every week? They’re the real-life Siegebreakers.

The oppressed in my novel Siegebreakers spend their entire page counts trying to resolve the military problem that seems to hold in several of today’s seemingly endless conflicts – whether it’s Israel’s wars on Gaza, in which the book is set, or it’s the Saudi dictatorship’s war on Yemen. In both cases, the more powerful side (Israel and Saudi Arabia), with all the backing and blessing that the US can provide, cannot seem to militarily defeat their outnumbered, outgunned opponents (the Palestinian resistance in Gaza – referred to simply as “Hamas” in the West, and the so-called “Houthis” in Yemen). So, the stronger side reverts to aerial bombing, destruction of civilian infrastructure, killing large numbers of civilians from the air, siege, blockade, and deliberate, genocidal destruction of the economy.

Israel’s 2006 war in Lebanon had a similar character: As it had decades before, Israel bombed the cities and invaded on the ground. Israel’s ground forces were defeated by their Lebanese opponents, Hizbollah. So they withdrew their ground forces and bombed the country for several weeks. In Israeli media there is frequent talk about the next war with Hizbollah, which is supposedly ‘inevitable’ (as is the next war with Gaza, as is war with Iran, etc.) In this hypothetical next war, Israeli leaders have pledged much more thorough bombing of Lebanon, including the usual promises to send it back into the stone age (the idea that these are war crimes seems no longer relevant: it may become relevant again). For their part, Hizbollah has warned that the next war won’t take place in Lebanon alone.

Returning to Gaza, the battle scenes in Siegebreakers are based on Israel’s 2014 war in the territory, and are portrayed, as the saying goes, from both sides. Ari’s experience as a soldier in the Israeli Army is drawn from various sources, but I highly recommend the report This is How We Fought in Gaza, by the group Breaking the Silence. If you find what Ari sees in Gaza shocking, read that report and you’ll see that, as I wrote in the Afterword, the most outrageous things in Siegebreakers are the true things. On the other side, Nasser’s experience fighting the invaders in Gaza draws from, among many other sources, Max Blumenthal’s book, the 51 Day War. Blumenthal traveled to Gaza shortly after the assault, while memories were still fresh, and documented what the war looked like on the Palestinian side. I got the chance to praise him for the book in a podcast in May 2019.

In Siegebreakers, the impasse gets broken in a particular way. I can’t tell you how, despite my love of everything to do with spoilers.

In a slightly better world, one with a powerful anti-war and anti-imperialist bloc within the US, these military impasses would lead to more energetic diplomatic initiatives. But in our world, there’s no need for diplomacy if you have America on your side (which apparently is cheaper and cheaper to attain). The fictional Siegebreakers rely on a few American dissident super-sleuths. The real-life Siegebreakers are part of a multi-decade slog to build an peace movement strong enough to change the current equation.

[This is one of a series of blog posts about the politics of my 2019 thriller novel, Siegebreakers, in which a team of heroes battles to break the siege on Gaza. Much of the politics and technology of the book is discussed and referenced in the Afterword: here I’ll take on specific issues once in a while and extend the discussion.]

One of the goals I had in writing Siegebreakers was to “de-exoticize” Palestinians, and along the way, Arabs and Muslims. The best way to explain what I mean is through an example.

In Siegebreakers, you won’t hear any of the Arab-speaking characters say “Allah”, “Inshallah”, “Ya Allah”/”Allahu Akbar”, or “Mashallah”. Instead, I use the most colloquial English translations: “God”, “If God wills it”, “Oh God”, or “Thank God”. In Western writing, media, and pop culture, using Allah instead of translating to God, or even using literal translations like “God is Great” instead of just “Oh God”, is exoticizing. It creates a distance between the Arab-speaking character and the English-speaking reader, and one that is unnecessary.

I say it’s an unnecessary distance because there are times when real cultural differences exist and come into play in interactions between people – on a human level and on a political one. But in the case of “Allah” and “God”, these words are used the exact same way by Arab-speakers and English-speakers, at the exact same times and in the same contexts. There isn’t a cultural difference between someone who sees something horrific and says “Ya Allah” in reaction and someone who says “Oh God”. It’s an artificial difference.

One way that Arabs great each other in the morning is to say “Sabah al Khair”, to which the response is “Sabah al Nur”. I’ve read one book (I won’t say which or by whom, no need to get into that here) where the author (a Westerner) renders the Palestinian characters saying “Morning of Joy,” and the response as “Morning of Light”.

What’s wrong with “Good Morning”?

That’s what I’d call exoticization – it really does just mean “Good Morning”.

Like so much in Siegebreakers (and I’d argue every other piece of art you’ve ever read, I’m just more honest about it) there’s a political agenda behind the de-exoticization. The distance between Western readers and even fictional Palestinians is part of what makes Westerners accept the injustices that are happening in Israel/Palestine. Exoticization extends that distance.

I don’t de-exoticize everywhere. Elsewhere in the book, reminding readers of the science-fiction nature of high-tech warfare and surveillance conducted on Palestinians by Israel is done through science-fiction like world-building techniques. The best exoticizer of the present that I know is author William Gibson. Decades ago, Gibson wrote science fiction (with a lot of implicit critique of corporate power and capitalism and where things were headed with computers and the internet…), whereas his more recent novels are set in the present, though they are still adventure books with extensive world-building, science, and technology in them. It’s just that our reality is science fiction now, so Gibson doesn’t have to speculate so much as describe the present.

When I went to Occupied Palestine in 2002, I felt my lack of Arabic and decided to remedy it (not entirely successfully, as you’ll see). Back in Toronto I took three years of university Arabic – it was my good luck to have the same Palestinian linguist for a professor even though it was at two different universities over several years. I got an A in Beginning Arabic, a B in Intermediate, and a C+ in Advanced (probably the plus was pity – I had too much going on by the time I was in advanced Arabic to apply myself properly). When I thought about how to render some of the Arabic conversations that I imagined, I heard my professor’s voice: she insisted that Allah was just the Arabic word for “God”, and that we translate it as such. So it’s not just a political or literary imperative: de-exoticization also keeps me out of trouble with my Arabic prof.

We are gonna launch Siegebreakers the evening of October 4th, at the marvelous Another Story Bookshop in Toronto, at 7pm. There’ll be a special guest there in addition to me, talking about the real Gaza. See you there!

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

I wrote Siegebreakers because I can’t liberate Gaza or Palestine, but I can dream about it. I wanted it to be a proximate dream, a dream of the next step from now, not a distant dream that depends on too many unpredictable things going right. I wanted to write about how just a few things going right could change the whole thing—to show, through fiction, the real fragility of the apartheid system that always seems so invincible.

Gaza is besieged. Its children are systematically malnourished. Its economy has been under an active program of what scholar Sara Roy called “de-development” for decades. Israeli drones watch everything that happens. Israeli towers guard the wall that surrounds the enclave on three sides. On the side facing the sea, Israeli gunboats shoot at its fishers. At their own discretion, Israeli warplanes and artillery drop bombs where they please, always with the most convincing of pretexts. Sometimes they are solemnly warned by other Western politicians to ensure their bombs are not excessive for their self-defense. Other times, it is the Palestinians who are told that the bombings are their own fault.

It should have been a sleepy beach town, a place where oranges are grown and where kids play soccer and tourists come to feel their feet in the sand. Instead it is an experiment in human despair, its population imprisoned and punished for the crime of being Palestinian.

When I went to Gaza in 2002, I had just visited Jenin. The Israelis had turned most of the center of the camp to rubble. I saw the Israelis blow up a bank, for some reason I still don’t understand. But Gaza was still scarier. The first thing I saw after crossing at Erez was an Israeli armored bulldozer, bulldozing orange trees. I paused to take a picture and was immediately told to put the camera away and move on—from a loudspeaker I hadn’t noticed until after I’d been given the order.

It’s been 17 years since that visit under the auspices of the International Solidarity Movement. ISM had been inspired by previous solidarity movements, perhaps starting with those Americans who traveled to Nicaragua to try to bring attention to the U.S.-backed Contra insurgency in the 1980s, part of the Central American wars that Bernie Sanders has recently—and to his credit—not apologized for opposing. In the 1990s, the Zapatistas in Chiapas further developed the ideas and practices of international solidarity with their observer programs. International observers in Zapatista communities were obliged to study the Zapatista struggle and to think of solidarity as a reciprocal practice, not a gift from benevolent Westerners to the struggling poor people in the global South. People who travel from the global North were always asked by the Zapatistas: what are you doing for the struggle back where you live?

All struggles against injustice on this small planet are intertwined, whether we see the links or not. With Palestine it takes real effort to miss the links: the U.S. Congress and other state legislatures pass bills to oppose the small, nonviolent BDS movement whose goals are to sanction Israel until it complies with international law; Ilhan Omar is made to apologize for mentioning that there is an Israel lobby that tries to influence U.S. policy in Israel’s favor; Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez apologizes for even speaking to Jeremy Corbyn, who in turn is demonized as an anti-semite even though everyone knows that he is a lifelong anti-racist whose real crime is supporting Palestinian rights. As it walls in and starves the Palestinians on all sides, Israel receives billions of dollars every year in aid, and many politicians in the West fall over themselves to embrace it (and condemn the Palestinians and their advocates). Palestine is where Israel’s high-tech arms industry tests out its anti-civilian weapons, exporting them as “battle-tested” in the laboratory of the occupation. Whether you want universal health care, school desegregation, for children not to die in concentration camps, or a Green New Deal, you won’t be able to sidestep the issue, tactically back down, or diplomatically leave it off the table for now. The chosen rhetorical weapon to attack socialist, democratic, redistributionist, and anti-racist leaders is Israel, whether it’s Corbyn in the UK or Omar and others in the U.S. There is no understanding how the empire works today without understanding the Palestinian struggle.

The empire wants the total dehumanization of the Palestinians, especially those Palestinians who resist. If they can be dehumanized, they can be isolated. If they can be isolated, then Israel is free to do what it wants to them. And since what Israel wants is the land without the people, the idea is to make the people go away. The policy, enabled by nearly all Western politicians and media, is genocidal.

Palestinian artists and writers do the work of humanizing: Susan Abulhawa’s Mornings in Jenin is in the literary genre; Mischa Hiller’s Shake Off is a dark thriller. Both writers show you the exterior worlds and the interior lives of extraordinary Palestinian characters living through brutal times.

For leftists, fiction is always part of the trade. A generation ago, Ghassan Kanafani, a political leader assassinated by Israel in 1972, wrote Men in the Sun and several other indispensable political novels of Palestine. Here in our time, Arundhati Roy writes both nonfiction essays analyzing the dynamics of war, empire, and capitalism and novels that take you along with people living through the same dynamics. Roy’s latest book The Ministry of Utmost Happiness ends with the creation of a small and fragile utopia, a community of people taking care of one another—in a cemetery.

Utopias, big and small, have a special place in leftist writing. Science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson, who has said that “science is now a leftism,” writes utopias because “anyone can do a dystopia these days just by making a collage of newspaper headlines, but utopias are hard, and important, because we need to imagine what it might be like if we did things well enough to say to our kids, we did our best, this is about as good as it was when it was handed to us, take care of it and do better. Some kind of narrative vision of what we’re trying for as a civilization.” Robinson was talking to another utopian writer, Terry Bisson, whose extraordinary novel Fire on the Mountain imagines what American history would have been like had John Brown succeeded in his raid on Harpers Ferry. Australian leftist writer Tamara Pearson concludes her novel The Butterfly Prison—which showcased how dystopic life can be for poor people in the West—with the struggling characters winning a revolution and starting to build a better world.

When I wrote Siegebreakers it was important to me for the titular characters to succeed beyond what we have seen in the real world, for reasons similar to those articulated by Robinson: the siege is crushing the people who live under it, but it is crushing all of our imaginations. It is only twenty years old, and it can be broken. If we can’t do it easily right now, we can at least imagine it. We certainly won’t be able to do something we can’t imagine. I want at least imagining a free Palestine and a free Gaza to become commonplace.

My other goal in writing Siegebreakers was to go beyond humanizing Palestinians and lionize them. I’m as much of a pop culture critic as anyone, but I grew up in the 1980s watching Transformers cartoons and reading Marvel comics, reading Encyclopedia Brown mysteries as a kid and Sherlock Holmes in my teens. I played Dungeons and Dragons well into adulthood and I still read every Jack Reacher novel within three days of it coming out. As a fan, I am obsessed with superpowered heroes facing even more powerful villains and winning because of cleverness and courage.

North Americans are conditioned to accept quite a bit of violence from our heroes. Jack Reacher kills more people than the villains in his novels, as author Lee Child famously said. In real life, Palestinians are always asked to be nonviolent, while Israel starves and kills them freely. At least in fiction, I wanted to read a thriller where the action heroes were fighting occupation. Ghassan Kanafani said in an interview that history was a struggle of the strong against the weak. But North American fictional heroes aren’t weak: they’re strong. For me, Siegebreakerswas a study of heroism. Was the idea of a hero pure propaganda meant to sell toys and militarism to the younger version of me? Or is it an important concept that I could reclaim and map onto different contexts? I’ve concluded it’s the latter. Heroes are real: a hero is someone who takes risks and makes sacrifices for others. In the context of Israel/Palestine, heroism means facing a superior force (Nasser, the Palestinian protagonist of Siegebreakers), it means sacrificing belonging in one’s country to stop oppression (Ari, the Israeli character), it means getting involved when your privilege means you could just look away (Maria, the American character).

I am not Palestinian or Israeli and I don’t claim any rights to represent anyone. Often with Palestine, making it a Muslim, or Arab, or Palestinian, or Israeli, or Jewish issue has been another way of trying to sweep it under the rug.

In any case, to me, writing is never about speaking for people—unless you’re the official spokesperson for an organization writing official communications—much less claiming their struggle. You don’t have to be what you are writing (only memoir can do that). You just have to know what you’re talking about. Readers who know can decide what they think of Siegebreakers.

Artists do things because they are moved and hope to move others. What Israel, with ample help from the U.S., the UK, the EU and Canada, Egypt and Saudi Arabia and so many others, is doing to the Palestinians breaks many people’s hearts, including mine. So does what the Palestinians do to live and take care of each other in the face of it all. If it isn’t breaking yours, maybe my book can help.

First published by MR Online.

Siegebreakers (Roseway Publishing) hits the shelves on September 2.

A podcast from Electronic Intifada features Siegebreakers. That’s pretty exciting for me because Electronic Intifada are my media heroes.

I talk to Greg Shupak, author of The Wrong Story: Palestine, Israel, and the Media. We use the Israel/Palestine story as a launching point for a technical discussion about tropes, frames, narratives, and propaganda, and about why and how to argue against it all.