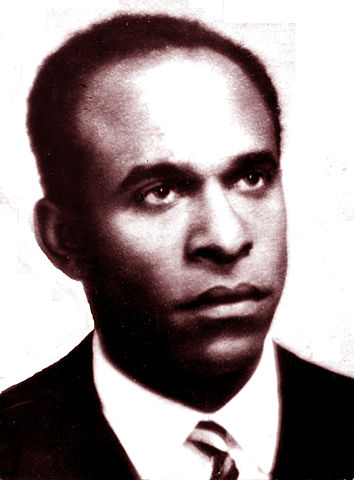

Stefan Kipfer and I talk about the lessons we learned from reading the revolutionary Frantz Fanon, author of The Wretched of the Earth and Black Skin, White Masks.

Category: Leftist theory

Occasional forays into leftist theory about what a good society might be like, and how leftists can use social theory to help understand the world.

Why most anti-bullying programs don’t work – and how to fight bullying – video

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 45: How will the working class respond after COVID-19? With Sam Gindin

I talk to Sam Gindin about capitalism and the COVID-19 crisis. We started with economics, but it is really about consciousness, politics, expectations, and the struggles ahead.

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 44: Bernie quits; and don’t be progressive

Justin and Dan start by grieving because Bernie ended his presidential bid today. Then on to a history the imperialism and racism of the Progressive Era and why “progressive” and “leftist” are words for two different politics.

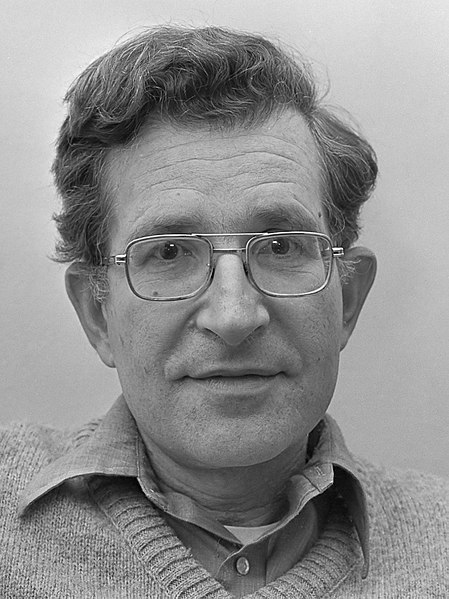

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 43: Two Chomskyites Trapped in 2020

Justin and Dan (that’s Dan Freeman-Maloy, for new listeners) talk about Chomsky – and not just manufacturing consent, but Chomsky’s influence on their political thinking, where they might have tiny disagreements, and how they try to use Chomsky’s work to think through political problems in 2020.

Depressed? Anxious? It’s a social problem.

In today’s video I review the insights in Johann Hari’s book Lost Connections, as well as gems from leftist psychologists like Bruce Levine, Paul Moloney, and Gabor Mate. If you’re quarantined and feeling low, here’s a leftist take on why.

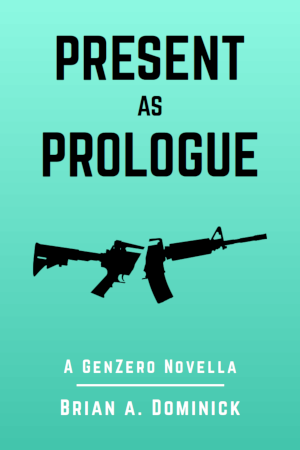

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 39: Might, the novel, by Brian Dominick

Brian Dominick is the author of Present as Prologue: A GenZero Novella, which describes the first phase of a youth-led, high-tech revolution in America. We talk about youth liberation, education, capitalism, and the liberatory possibilities and limitations of technological change. Interesting discussion about the idea of youth as a class.

Readings for leftist parents

A little video talking about some of the readings on parenting I found most helpful, and most compatible with leftist values (equality, freedom…)

The Anti-Empire Project Episode 37: Postcoloniality and the Racist Legacy of the British Empire

A wide-ranging and admittedly bookish discussion with William Patterson historian Navyug Gill and frequent guest and sometimes host of the show, Dan Freeman-Maloy. We talk about postcolonial studies, history, and the British Empire, and the ways that its racism lives on.

Three Lessons this Leftist Takes from Trump’s Victory

I have been surprised by two electoral events in a few months: Trump’s election victory and the Colombian referendum on the peace accords. Both votes were very close, had low participation rates, and were expected to go the other way. If I were a closer watcher of British politics, I would no doubt have been equally surprised by the Brexit vote. In trying to learn from my own errors of analysis, I have come to these conclusions.

1. This is a world of bubbles.

One important and constant argument made on the left is for the need for independent media. The reason we believe in devoting resources and energy to creating and supporting independent media is to try to reduce our dependence for information on analysis on corporate media sources. Whether those sources support Democrats or Republicans, whether they are liberal or conservative, their corporate values and their business models trump the political considerations of their journalists or editors.

We used to focus our analysis of media bias against the corporate, agenda-setting media and especially their flagship newspaper, namely the New York Times. The NYT would receive the most criticism, not because it was the most biased, because there have always been many outlets to the right of it, but because it had the most influence. With the decline of newspapers and more and more people getting their information from different media – TV, social media, other web sources – audiences fragmented.

That fragmentation process is now complete. The agenda-setting media set agendas for only one bloc of Americans. Another bloc, the one that just elected Trump, uses a different set of media – one with its own set of assumptions and biases.

So my daily media routine goes like this: I use a carefully curated Twitter feed, following journalists and writers that I like and trust. When I have analyzed what I end up reading via Twitter, it seemed to me that I was clicking a lot of links to The Guardian, The Intercept, and Al Jazeera.

I make a daily round of outlets that I like and contribute to – Znet, TeleSUR, Ricochet, rabble, and some foreign outlets like El Tiempo in Colombia. I avoid material that depresses me except when I’m doing direct research on a topic. Because I don’t like to be made miserable constantly, I also look for news that is already presented with some analysis or even comedically – like John Oliver’s show. Because I actually want to write and do things, I don’t have time for much more than this or I would be consuming news all day.

In other words, I live in a bubble of my own selection. Being in that bubble is helpful to me because I know I have a community of people who I respect, who are like-minded and I get to spend time reading their insights. But left media outlets don’t have systematic surveying of every part of the US. For that kind of resourced, comprehensive coverage, I looked to the corporate media for insight – the NYT, CNN, etc. I relied on their news and their polling and tried to build my own analysis from there. And consequently, I was completely wrong.

I don’t think that there’s some alternative like scanning every bubble or spending lots of time interacting with media that supported Trump. You can get insights from inside your bubble. Arlie Russell Hochschild did serious research on what was driving support for Trump, and delivered it straight into my bubble on Democracy Now. Michael Moore predicted a Trump victory. The starting point though has to be that there is very little that forms a common basis for a national conversation – there are several different conversations going on with different assumptions and starting points. Fox News and Clear Channel on the one hand and the NYT and MSNBC on the other are all corporate media, but their audiences don’t understand each other and underestimate each other.

2. The poll that matters is the election.

Campaign strategists and voters relied on polls, and the polls were wrong. Politicians use polls to try to campaign scientifically, focusing attention where they can make gains according to how they are polling in the elections. But the polls are pseudo-science. In the last three elections I have followed closely (Canada 2015, Colombia referendum, and this last US election) I had a completely incorrect idea of what was going to happen because I relied on the polls.

With everybody, politicians and public alike, watching the polls, the election becomes more like a pseudoscientific exercise about watching percentage points go up and down and less like a public conversation about politics, policies, and laws.

3. The conservative base is not growing.

In Canada 2015, Stephen Harper lost the election with nearly the same number of votes (5.6 million) with which he won a majority in 2010 (5.8 million). Trump won the presidency in 2016 with 60.3 million votes, while Romney lost in 2012 with 60.9 million. In both countries the conservative base is not growing, but slowly shrinking. When they lose it is not because their base grows, but because the other side gets more votes (in the cases of Trudeau and Obama, a lot more votes).

Obama (2008, 2012) and Trudeau (2015) were able to generate enthusiasm that Clinton was not. Perhaps Sanders would have generated that kind of enthusiasm, but he did not win the nomination. Many leftists who want substantive moves towards greater equality and peace were excited about Sanders, but neither Obama nor Trudeau really promised such moves. They won anyway. The Democratic Party might not see a move to the left as the best strategy after this loss.

Trump may have won by promising to make America great again, but he is incapable of solving or even understanding any of the problems we face. Solutions for environmental, social, and international crises will have to come from the left. Surviving the Trump presidency will be a challenge.

Independence of thought will be an important survival skill.