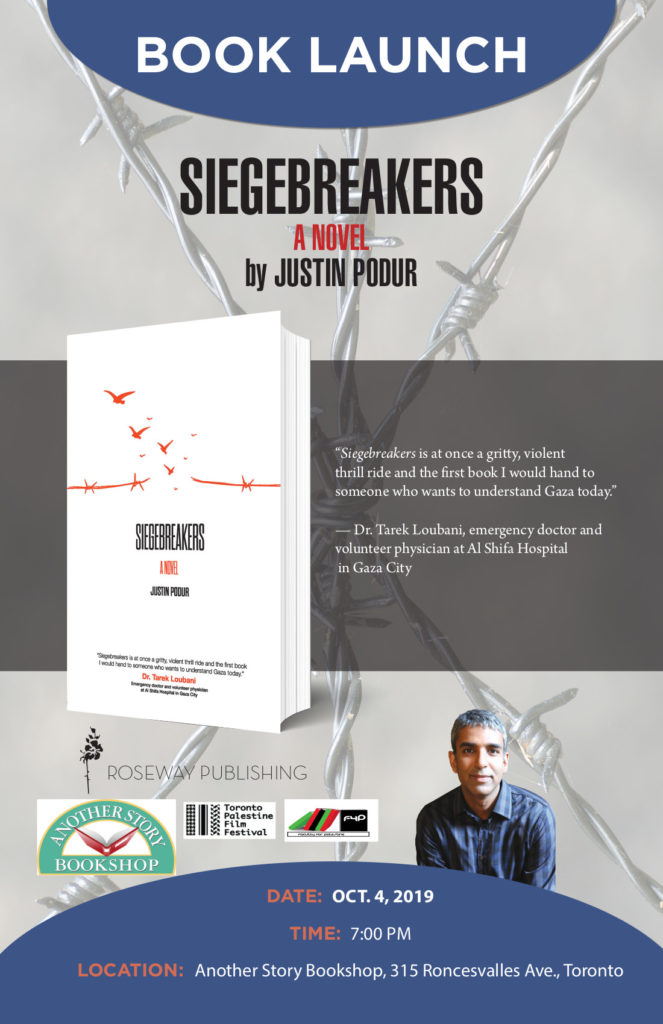

The oppressed in my novel Siegebreakers spend their entire page counts trying to resolve the military problem that seems to hold in several of today’s seemingly endless conflicts – whether it’s Israel’s wars on Gaza, in which the book is set, or it’s the Saudi dictatorship’s war on Yemen. In both cases, the more powerful side (Israel and Saudi Arabia), with all the backing and blessing that the US can provide, cannot seem to militarily defeat their outnumbered, outgunned opponents (the Palestinian resistance in Gaza – referred to simply as “Hamas” in the West, and the so-called “Houthis” in Yemen). So, the stronger side reverts to aerial bombing, destruction of civilian infrastructure, killing large numbers of civilians from the air, siege, blockade, and deliberate, genocidal destruction of the economy.

Israel’s 2006 war in Lebanon had a similar character: As it had decades before, Israel bombed the cities and invaded on the ground. Israel’s ground forces were defeated by their Lebanese opponents, Hizbollah. So they withdrew their ground forces and bombed the country for several weeks. In Israeli media there is frequent talk about the next war with Hizbollah, which is supposedly ‘inevitable’ (as is the next war with Gaza, as is war with Iran, etc.) In this hypothetical next war, Israeli leaders have pledged much more thorough bombing of Lebanon, including the usual promises to send it back into the stone age (the idea that these are war crimes seems no longer relevant: it may become relevant again). For their part, Hizbollah has warned that the next war won’t take place in Lebanon alone.

Returning to Gaza, the battle scenes in Siegebreakers are based on Israel’s 2014 war in the territory, and are portrayed, as the saying goes, from both sides. Ari’s experience as a soldier in the Israeli Army is drawn from various sources, but I highly recommend the report This is How We Fought in Gaza, by the group Breaking the Silence. If you find what Ari sees in Gaza shocking, read that report and you’ll see that, as I wrote in the Afterword, the most outrageous things in Siegebreakers are the true things. On the other side, Nasser’s experience fighting the invaders in Gaza draws from, among many other sources, Max Blumenthal’s book, the 51 Day War. Blumenthal traveled to Gaza shortly after the assault, while memories were still fresh, and documented what the war looked like on the Palestinian side. I got the chance to praise him for the book in a podcast in May 2019.

In Siegebreakers, the impasse gets broken in a particular way. I can’t tell you how, despite my love of everything to do with spoilers.

In a slightly better world, one with a powerful anti-war and anti-imperialist bloc within the US, these military impasses would lead to more energetic diplomatic initiatives. But in our world, there’s no need for diplomacy if you have America on your side (which apparently is cheaper and cheaper to attain). The fictional Siegebreakers rely on a few American dissident super-sleuths. The real-life Siegebreakers are part of a multi-decade slog to build an peace movement strong enough to change the current equation.